Ellen Nielsen, “Spectacle Box”, 2007. Sequins, pins, wood, glass, velvet, 9″ x 18″ x 3″. Courtesy of the artist.

Last September, DePaul Art Museum hosted an epic group exhibition, featuring Imagist artist work on the first floor and a contemporary generation of artists on the second. While those contemporaries have in many respects plotted their own independent and respective courses, there was something refreshing about co-curators,’ Dahlia Tulett-Gross and Thea Liberty Nichols, ability to highlight the visual and theoretical connection between generations. The resulting exhibition, Afterimage, illustrated a visual legacy, reinvigorating the past while demonstrating it’s transformation into the present.

Caroline Picard: Often collaborative curatorial projects come from on-going conversations — how did you two conceive of the Afterimage show?

Thea Liberty Nichols: You’re right on target in thinking that the show evolved through a series of ongoing conversations, but ultimately, Dahlia came up with the idea. She’s connected to a lot of local galleries and has built relationships with dozens of artists. Recognizing a renewed interest in the Imagists among contemporary artists who, rather than obscure or reject their connection to them, prized it, she isolated a certain look or feel that many of those artists shared with the Imagists. She approached me about co-curating with her partly because I had written my thesis on the Imagists. Ultimately, our commitment to showcasing the work of every artist as an individual within the larger context of our show led to the publication of an exhibition catalog, which we were so pleased to include you in!

CP: What was so important about platforming art with writing in the catalogue?

TLN: We were dedicated to creating some enduring historical record since, like Imagism itself, there’s a lot of historical background noise about art writing in Chicago — both its quality and its outlets, or lack there of. In both instances, rather then engage distant and stale debates, we wanted to have a new conversation featuring new voices. We were lucky to work with a whole host of arts writers, including arts journalists, critics, curators and even some visual artists who also write for our publication.

Tangentially, the same openness to collaboration and fluid thinking through and around a concept evolved into a really rich mode of working for us. It cultivated the organic expansion of our exhibition across multiple institutions and host sites, including The School of the Art Institute’s (SAIC) Roger Brown Study Collection and Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection, and Columbia College’s Center for Book and Paper Arts. It also attracted likeminded projects to us, such as Pentimenti Productions, a film company working on a feature length film titled Hairy Who and Chicago Imagists. We partnered with them to conduct interviews with some of the artists in our show and capture footage of the exhibition’s opening night [as seen in the excerpt linked here from Afterimage by Pentimenti Productions].

Afterimage documentation courtesy of Chicago-based Pentimenti Productions, producers of the forthcoming feature documentary Hairy Who & The Chicago Imagists.

CP: How do you characterize the Imagists?

TLN: The term Imagism has served many masters over the years, and it’s elusive — and somewhat divisive — definition has received various receptions from the artists its been applied to. I think when Franz Schulze initially coined the term, he used it to describe the work of a generation of his peers working mid-century. Artists like Leon Golub, who are now commonly known as “the Monster Roster.” Dennis Adrian used the term Imagism to categorize a group of six artists (James Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca and Karl Wirsum) who exhibited at the Hyde Park Art Center in 1966-68 in a series of self-titled exhibitions called the Hairy Who. Its since evolved into a relatively plastic term that encompasses all of these artists and more, including Ray Yoshida, Roger Brown, Ed Paschke, Christina Ramberg, and Phil Hanson — almost all of whom were in our exhibition.

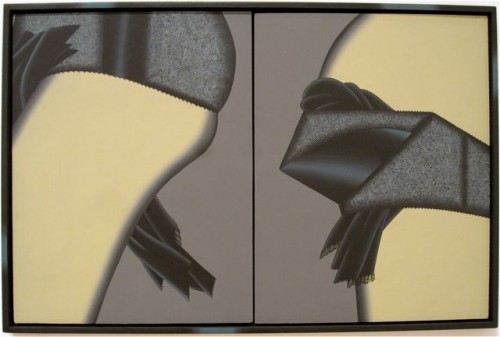

Christina Ramberg, “Loose Beauty”, 1973. Acrylic on board, 19 1/8 x 29 1/2″, diptych. Photo courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago.

As curators, Dahlia and I thought more about what Imagism’s definition was in relationship, or contrast to, Afterimage’s contemporary artists. The title of the exhibition refers to the optical phenomenon when something in your field of vision persists even after exposure to it has ceased — think ghost image due to retinal burn. We felt that neatly summed up the persistence of Imagism in Chicago, and elsewhere, decades after its emergence. We liked the punniness of the term, too, since our show featured artists literally working “after” Imagism, both in the historical sense and in the sense that they were working in some sort of aesthetic relationship to it.

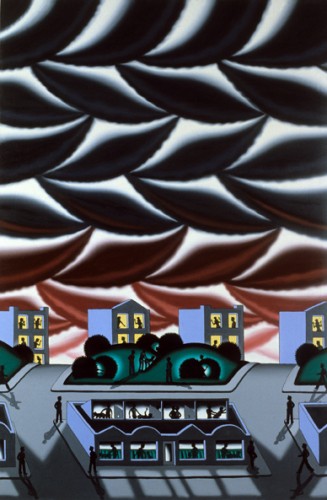

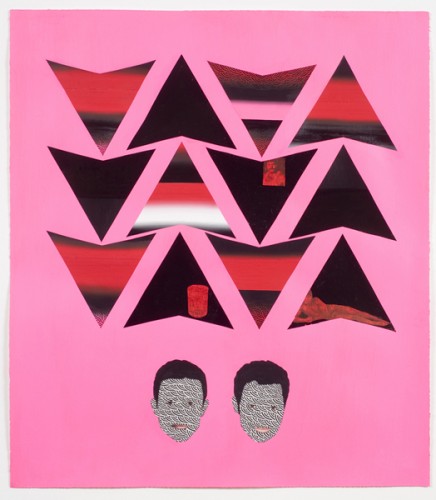

There was a whole range of approaches these relationship took; some pieces shared a visual vocabulary with Imagism, and resonated strongly with its intense color palette, meticulous level of finish, and busy pictorial arrangements, with their preference for bilateral or indexical arrangements of form. Some artists reveled in a similar brand of black humor. In addition, there was a lot of overlapping subject matter in regards to gender issues and the employment of personal narrative. Lastly, and perhaps most prominently, were the shared art historical, pop cultural, vernacular or commercial references that the artists in Afterimage shared with the Imagists, drawing inspiration from, and even sometimes visually quoting, works by Öyvind Fahlström, Basil Wolverton and Joseph Yoakum among others.

In everything we did, we tried to stay artist centered and content driven — appreciating that the contemporary works stood on their own, and were open to multiple readings. Not every work in the show neatly fit a category, but that dynamism excited us. We never tried to put forth an exhaustive list of artists working in relationship to the Imagists, or suggest that the artists we were able to include comprised some sort of unique entity or “ism” unto themselves.

Roger Brown, City Nights: All-You-Wanted-to-Know-or-Don’t-Want-to-Know-and-were-Afraid-to- Ask A Closet Painting (subtitle supplied by Barbara Bowman, 1978, oil on canvas, 72 x 48 in. Roger Brown Estate Painting Collection, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Photograph: William H. Bengtson.

CP: How do you think about aesthetic influence? I’m thinking partly about this quote from the Bad at Sports LP. Someone states that in most cities young artist kill their aesthetic predeccessors — you rebel against and upturn the past, in order to create new, independent works — he said in Chicago we don’t do that. We always love our artistic ancestors.

Dahlia Tulett-Gross: The contemporary artists in the exhibition either studied with the Imagists, were influenced by or shared influences with them. While these artists have held on to certain Imagist “values,” they have also moved through and beyond it. Take Steven Husby for example — his work is finely crafted, with slick surfaces like the Imagists, although it is essentially abstract with no reference to narrative.

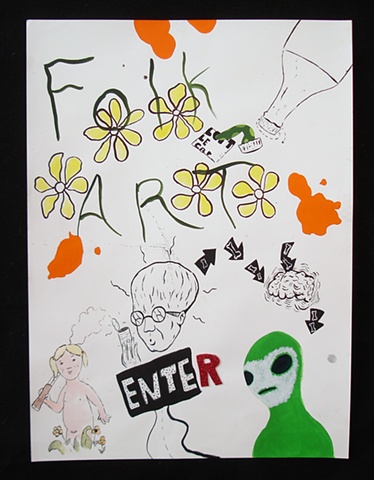

Or David Leggett, who explores personal narrative, although his work isn’t physically “tidy” like the Imagists. Ultimately, the artists represented in Afterimage carve their own path to create work that wouldn’t be confused with Imagist work.

David Leggett, “Summer of Dreams and Magic”, 2010. Mixed media on paper, 22″ x 30″. Courtesy of EBERSMOORE Gallery.

I believe that many prominent artists in Chicago turned away from Imagism. Artists like Richard Rezac, Julia Fish, Dan Peterman, Judy Ledgerwood, Tony Tassett, Gaylen Gerber, and Michelle Grabner rejected personal narrative in favor of broader conceptual issues. That said, I find it interesting that many of these artists make finely crafted, patterned or time intensive work — all traits of Imagist work.

TLN: Our ideas about influence — and the circuitous routes it travels — certainly mutated over the two years spent planning the show. The further along we got in our research, and the more studio visits we conducted, the clearer it became that ideas flowed rhizomatically between teachers, students and from peer to peer. Both generations of artists draw inspiration from each other, and the world of art, but also from outside of it, across disciplines, media, time periods and physical locations. The auxiliary programming we scheduled in conjunction with Afterimage reflected this multi-dimensional arts practice, including live musical performances, a food truck and a monumental “jam” comic installation.

CP: Can you talk more about this “rhizomatic” relationship?

DTG: The teacher/student relationship was absolutely integral to the Imagists, who often site Ray Yoshida and Whitney Halstead, among other professors that they had at SAIC as being major influences. Those teachers went beyond the classroom, taking students to the Field Museum, the historic Maxwell Street Market, and other places to find unconventional treasures as source material for artwork.

The Imagists shared close friendships with many of these professors, allowing for an exchange of ideas. Similarly, some of the contemporary artists in Afterimage shared personal relationships with the Imagists. Richard Hull went from student to showing alongside the Imagists at Phyllis Kind Gallery. One of his paintings hangs in a prominent spot in Roger Brown’s house.

John Parot, Navarro’s Problem, 2010. Gouache, enamel and ink collage on paper, 34″ x 30″. Courtesy of Western Exhibitions.

CP: Do you feel like your experience of the Imagists’ work has changed?

DTG: Thea and I have talked about how fresh and exciting the Imagist work still looks. Perhaps because they didn’t follow the dominant trends of their own day, they created work that still feels relevant.

TLN: Since we were able to include the work of a lot of comic and graphic artists in our exhibitions as well, we encountered first hand the palpable influence Imagism has had on the [comics] field— a funny full circle considering how influential comics were to the Imagists. I think a lot of the Imagist aesthetic, if you could boil it down to one thing, still feels relevant because it has become a ubiquitous mode of working for contemporary illustrators, comic artists, and is common place in things like music posters and certain zines and graffiti. The Imagists art practice itself is essentially what we’ve come to understand as post modernity.

Pingback: After Afterimage | The Lantern Daily

Pingback: April Blogger-in-Residence | Thea Liberty Nichols | Art21 Blog