Mandy Keifetz is a finishing school drop-out. She joins the blog this month as a guest writer for Ink. Keifetz’s work has appeared in the Massachusetts Review, Brooklyn Rail, .Cent, Penthouse, Vogue, Review of Contemporary Fiction, and many other publications. Entertainment Weekly called her first novel, Corrido, “an intoxicating cocktail of sex and death.” Her second novel, Flea Circus: A Brief Bestiary of Grief, won the AWP Fiction Prize in 2010, selected by Francine Prose, and was published by New Issues. The novel was a finalist in the 2011 Grub Street National Book Prize and was given Honorable Mention. She was a Fellow with the New York Foundation for the Arts in 2002, and her plays have been staged in London, Cambridge, Montréal, Oslo, and New York. She is an occasional MFA dissertation defense panelist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and a jurist for the Scholastic Achievement Awards.

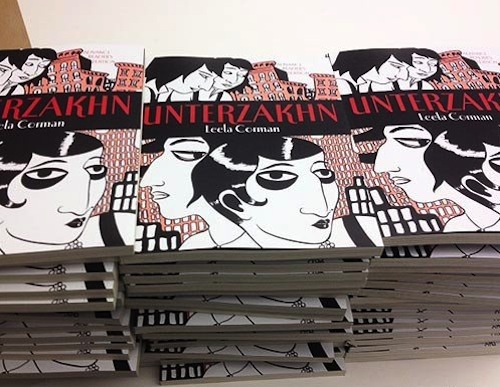

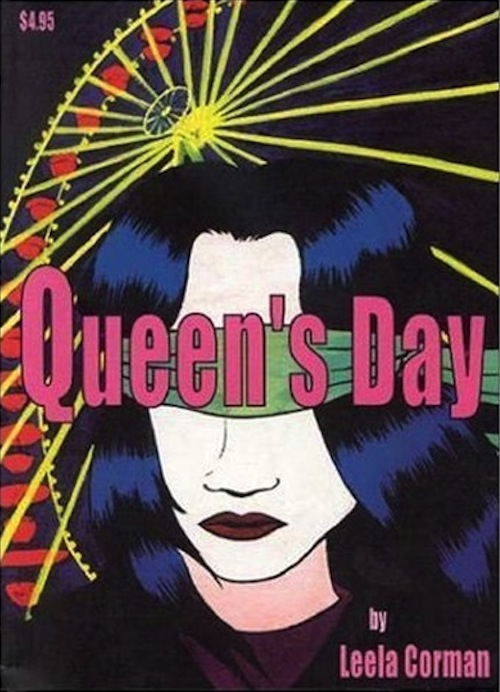

Leela Corman studied art at the Massachusetts College of Art. Her first book Queen’s Day earned her a Xeric Award in 1999. Her latest, Unterzakhna, a turn-of-the-previous-century tale of Jewish sisters living on New York’s Lower East Side, was published by Schocken/Pantheon. It has been called the lovechild of Los. Bros. Hernandez and Isaac Bashevis Singer but in its grittiness, narratively and texturally, I see more of Max Beckmann. Corman is also an accomplished bellydancer and bellydance instructor. She and her husband, Tom Hart, are the founders of The Sequential Arts Workshop, a non-profit organization offering instruction in comic art, graphic novels and visual storytelling in Gainesville, Florida.

Unterzakhn is beautifully shot through with Galitzianer Yiddish. The title itself means underwear, a reference to both the iconic image of fluttering underthings on clothesline strung between Old Law tenements, and, one is given to assume, the constraints on reproductive freedom which women of the protagonists era suffered. For the purposes of this interview, you may assume that pritze means both actual prostitute and sexually aware woman; that kurve means the same; that both akusherke and bobbe mean something like lady parts doctor. Ongeblussen is something like a narcissistic bloviator and nar a bit more like systemically disengaged from the serious. And altekacher is, more or less, old fart, but said with affection.

INK: This is a column about ink, so I thought we could start by talking about ink. Literal ink. Your actual materials and physical process. I don’t think comix people talk about this enough. Can you tell me a little about your relationship to the physical processes of the medium itself?

Leela Corman: I found my favorite ink and bristol board a long time ago. I use .07 mechanical pencils, Mars plastic erasers, liquid sumi ink and Strathmore 300 bristol vellum. I don’t deviate. As far as the rest of the physical process, drawing itself is a physical act, something I try to impress on students when I teach. That’s one reason I’ve taken to working very large: I don’t have room on smaller paper to use my arm when I draw. I like to work very small as well, but not for comics. I like to work small sometimes for individual drawings and paintings.

INK: The heroes of Unterzazkhn, Esther and Fanya, look a bit like Tina, the protagonist in Subway Series, and in both books the physical textures of the scenes matter, but the narrative complexity in Unterzakhn dramatically outstrips Subway Series. It is a leap which feels greater than a decade to me, although I believe the books were published at that interval. Could you tell us a little about how these two very different stories found you?

LC: Subway Series is such juvenilia, you know? It was the first time I applied any sort of process to writing and drawing. I don’t think I was successful in either category, but it was a learning experience. Subway Series is not autobiographical at all, but I did base it in the time and place of my adolescence. When I started it, we had just moved back to New York and that brought up a lot of memories and feelings about my adolescence that I’d suppressed in a headlong bid to grow the f*ck up.

Unterzakhn seemed to come to me very fast, but in truth it was also an extension–a re-sprouting?–of an idea I’d had and abandoned when I was still doing minicomics. I’d thought about doing a story about a Jewish showgirl in Poland before the war, but that never took off, because as it turned out, I’m sick of World War II, and others have said it better anyway, on that subject. So years later I got a flash of these twins and their parents, of their neighborhood and their basic life path, and then I spent a very long time hammering that into a coherent story. Neither story is at all autobiographical.

INK: Queen’s Day–which was your senior illustration project and for which you won a Xeric grant–was a triptych. It always reminded me of Otto Dix. I’m sure that seems a long time ago, but if there is anything you would like to say about your narrative muses for that story too, please feel free.

LC: Kids, don’t try this at home! I drew Queen’s Day with no plan, no preliminary sketches, nothing. I went to my desk every day and drew by the seat of my pants. I deliberately placed my washes on the sooty Chinatown windowsill and let them get gritty. I did it as my senior illustration project, with every intention of submitting it for a Xeric Grant. Narrative muses? I don’t know. I wish I knew! I was trying to work in stream of consciousness there, something I recommend doing maybe once, but not again! I’m glad you thought of Dix. You flatter me!

INK: The last person I spoke Yiddish with was my Great Uncle Isie who was a cab driver in New York. He died in 2003 at the age of 96. Where did you learn yours and have you found speakers amongst your readership?

LC: Well, I really wish I could actually speak it. I only know curses, endearments, and food words. Older readers who grew up speaking living Yiddish, as opposed to academic Yiddish, hadn’t heard of the title word before.

What little I have, and the cadences of it (which I have much more of), I learned at my mother’s parents’ table. Also, I used to wait tables in this really crazy diner in Boston owned by a grizzled West End Jew named Mike who liked to tell the other short order cooks to Vey Gehagn. I loved that guy.

INK: We leave Meyer Birnbaum as he’s being dragged off by Cossacks and next see him as the king of Tin Pan Alley. As a novelist first and a lover of comix second, I deeply wish to know how that drama queen got from point A to point B. Do you secretly know the backstory?

LC: You know, you are the only person who’s asked me about Meyer, and I think he’s the best character in the book! I know everyone wants to know how Meyer got out of that pickle back in Russia. His character is the clue. He’s an expert finagler.

INK: I think Meyer–both as a young Ongeblussen (or is he a “Nar”?) and an alterkacher–looks like he was drawn by Grosz which I love about him. Is this intentional?

LC: Well, no, but I love German Expressionism, and it is a huge influence on me as an artist, though I often think that influence is invisible. I worried that older Meyer looked like the Penguin from the old Batman TV show, actually, so I’m delighted that you read German Expressionism off of him. Did you see Glitter And Doom at the Met [Museum] a few years ago? It changed my life, although I already loved that era. I’d go so far as to say that those are my favorite painters. The cover was directly influenced by a Kirchner book.

INK: Are any of the characters based on people to whom you are related, or based on family stories about others?

LC: No. Though I did give Isaac my grandfather’s hair, and a little of his moral backbone. But there’s no similarity to the two of them. My grandfather lived a full life and raised a family, after being traumatized. He didn’t fade away. He wasn’t happy, but he was present. The character of Miss Lucille is one that anybody in a performance discipline involving women will recognize. She’s what none of us want to become–a drunk, embittered caricature of a femme fatale.

INK: In my family, you don’t have to go very far back before an unmarried woman was either a kurve (“pritze” to you, ya crazy Pole) or an akusherke. (Isie’s girlfriend Rose actually said “Bobbe” for both midwife and doula, and my discourse with Isie, of course, never touched on the gynecological.) Did you set the twins on those particular paths from that cultural place? Or, like your words for whore and midwife, are your family’s stories of immigrant New York different from mine?

LC: What are ya, Lithuanian?

The New York side of my family didn’t arrive until after WWII. I might be the only Jew from New York whose family didn’t come through the Lower East Side. They arrived in 1953 on a luxury liner. Though my grandmother told me that when she first saw the shore of NYC, she wanted to turn around and go back to Europe. They lived on the Grand Concourse and worked as tailor and seamstress. Papa was also a couture cutter and furrier.

No, the story is pure fiction from start to finish. Their career trajectories came to me in the same flash that told me their names, ages, relationship, and neighborhood. At that point all I knew was that I felt compelled to talk about the gruesome ramifications of women having no control over their reproductive lives, and I’m also obsessed with showgirls.

INK: A belly dancing cartoonist, it seems to me, serves the original three muses–Song & Practice & Memory–in equal measure, so I find nothing unholy in that combination even though I can hardly imagine how one does either thing. Is it discordant to you?

LC: No, the two art forms serve one another. Dance keeps me from going batshit from sitting too much, and my studies in that area have fed my comics work in ways that I haven’t even had time to fully put into practice yet. Also, if I didn’t dance, I’d never change out of my drab studio clothes.

INK: Your new book is about the Plague. I find the Plague Doctor to be one of the most secretly thrilling visual archetypes–Antonio Prohas’s Spies affect me the same way though so it is possible I just have a thing for beaks!—-will he make an appearance? And, of course, is there anything you’re ready to tell your readers about the new project.

LC: It’s partially going to be about the Plague. It’s really about dancers and entertainers in different time periods and cultures. Spy Vs. Spy always grossed me out! I can’t explain why. Those beaky creatures seemed disgusting to me. But yes, if the Plague doctor fits the country and social class of my story, you’ll see him and his rose-stuffed beak. Can you imagine being in a delirium and looking up to see that guy?

The new project is going to be amazing. It’s also going to need a huge amount of research. I’ll probably need to go to Turkey to do some of it. I have shorter-term stuff brewing in the meantime, while I learn all about buboes, kocek boys, and 19th century Egyptian circuses.

Editor’s Note: The Editions | Artists’ BookFair, which was canceled due to Hurricane Sandy, has been rescheduled. Opening night is Wednesday, January 23, and it will run through Sunday, January 27. Please note that it will also take place in a new location: The Altman Building, 135 West 18th Street (between Sixth and Seventh Avenues), NYC. The October 2012 issue of Ink discusses the fair in depth.