Beauty.

In 1993, Dave Hickey posited that the the art world was due for a reinvestigation of beauty. Here we are two decades later. The world hasn’t ended, and the subject of beauty in art remains a contentious one. In the face of a meta culture, the concept of beauty in art is still a hard one to contend with. Why? Because we have become jaded about beauty. Kathleen Marie Higgins writes that “we are more likely to resent beauty to than to love it. Beauty too easily becomes identified with a more perfect time, the imaginary point from which things have gone downhill.”

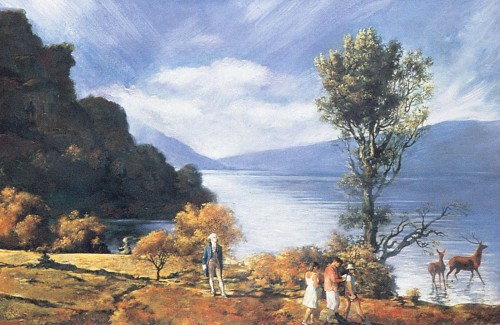

Higgins’s comment helps explain why the 1994 series People’s Choice by the Russian collaborative team Komar and Melamid is so poignant. (People’s Choice was made around the time that Hickey called for a return to beauty.) Komar and Melamid surveyed Americans to find out what the painting they most wanted would look like, thereby flipping the role of the artist as truth-maker and taste-disseminator to that of democratizer. Not surprisingly, 75% of respondents felt that “paintings don’t necessarily have to teach us any lessons, but can just be something a person likes to look at.” In response to the survey, Komar and Melamid made United States: Most Wanted Painting featuring plenty of blue (apparently, America’s favorite color) behind a landscape that included prancing deer and a small representation of George Washington. Perfection in oil.

Perhaps what this series reveals is the reason for the art world’s avoidance of beauty. Higgins describes our current culture as one that is riddled by smoke and mirrors. “American culture is cynical.” We distrust beauty. Higgins goes on to describe that “sensitive” people–which I take to mean the educated and culturally astute–“absorb disturbance more than beauty from their world.” When artists employ Beauty (with a capital B) then it must be contextualized or else its “propriety comes into question.”

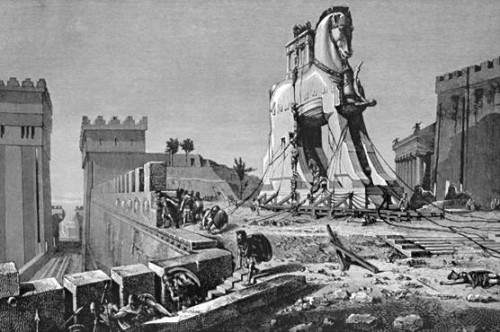

As I mentioned earlier, Komar and Melamid’s survey revealed that 75 percent of Americans favor a mirage of pastoral peace over cynicism and nuance. The current cultural trend in craft, a return to things that are conventionally beautiful, comes to mind here. To return to beauty (rather than to take up the avant-garde tradition of denouncing convention) signifies to me that artists are becoming “sneaky.” That is, rather than operating in a harshly political or controversial realm (take for example Andre Serrano’s Piss Christ), many artists today are choosing to co-opt the beautiful as a way of filtering in concepts about contemporary culture. Suzanne Perling Hudson writes that “beauty is…a kind of Trojan Horse, capable of smuggling disruptive ideas and concerns into otherwise disinterested institutional spaces.” I enjoy this analogy of contemporary artists as the divisive Greek army hidden in the Trojan Horse, as if they are delivering secret jabs behind the facade of beauty. As my last article asserted, the art world’s reliance on “this vs. that” and reactionary dualities has gone on long enough, and I believe that artists’ return to beauty proves that. Artists today operate in the meta–a nuanced environment that is anything but binary. Today, no painting of a pastoral scene featuring George Washington could be made and received (not to mention respected) without a heavy dose of irony.

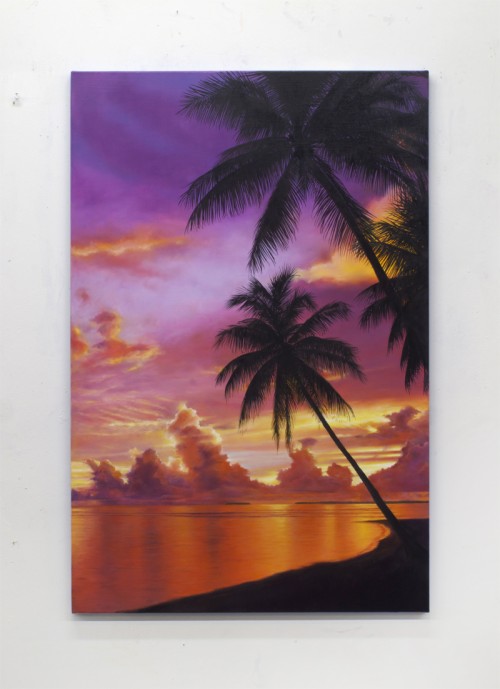

Take as another example the work of Martin Basher or Matt Lipps, two artists who employ a sort of traditional beauty yet slyly infuse it with humor, politic, poetry, psychology, and cynicism. Basher’s painting pictured above cannot be taken as a sincere effort to paint an idyllic sunset. It must be read in its context. By this I mean not only the time and place in which it was created but also as part of a larger installation of paintings and sculptural objects. Basher often uses the handles of Jack Daniels bottles to prop up such beautiful and meticulously rendered paintings. Enter humor.

Matt Lipps also relies on context to bring sly humor to his beautiful photographs. As Seth Curcio described his body of work HORIZON/S: “Lipps appropriates content from a late 1950s arts and culture publication that promises to offer a curated selection of international culture that will add a sense of sophistication to anyone’s taste. From these images, Lipps playfully explores what happens to the meaning of certain objects and images when you remix them into new systems and categories–altering both content and context.”

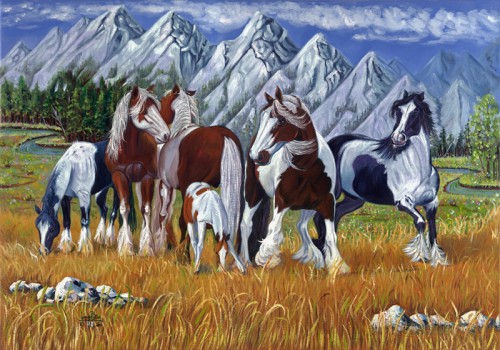

At the 2012 Whitney Biennial, I thought I had come upon a similarly cunning work: a small oil painting, titled Horse Nation, by Native American artist Leonard Peltier. Filled corner-to-corner with a traditionally beautiful pastoral scene, it seemed an ironic thing to hang on a museum floor entirely devoted to performance. That an entire wall (even if it was truncated) was devoted to this one painting seemed cynical. But how wrong my assumptions were. When I later researched the painting, I found that Horse Nation was part of an installation by Russian artist Joanna Malinowska. Also, I learned, Peltier painted Horse Nation while imprisoned. He was convicted, perhaps wrongly, for killing two officers during a riot on a reservation. Where I had read beauty in Horse Nation as irony there was none. Its display was in fact a subversive curatorial decision and politically-conscious act by Malinowska. Sly? Yes. But Horse Nation is actually antithetical to the kind of sneaky uses of beauty I am talking about in the work of Basher and Lipps.

Leonard Peltier, “Horse Nation” as seen in Joanna Malinowska’s installation for the Whitney Biennial, 2012.

Marshall McLuhen’s poignant words come to my aid: “The medium is the message.” Though, in the context of Malinowska’s installation, this is not the case. The beauty of Horse Nation is not connected to the political message that Malinowska intended. Malinowska is relying on the viewer to research or read wall text to gain insight into her concept. Since the “sensitive” among us, as Higgins puts forth, absorb more disturbance that beauty from the world, we are more likely to look upon a traditionally beautiful work of art with a cynical eye that to take the work at face value.

In contemporary art, irony has come to live beside traditional beauty. For this reason, I feel that any artist who hangs a pastoral painting such as Peltier’s should expect it to be read, by those of us who follow contemporary art, as an ironic or mocking gesture. However, this bucolic, feel-good scene is, I think, just what Peltier intended: creating beauty was an earnest effort. I find it problematic that it’s not until one knows Peltier’s status that the nuances of Malinowska’s installation start to emerge. While Malinowska is using a beautiful object, and displaying it to add nuance to her installation, what she’s doing is also quite cryptic. The medium and the message do not align in the same way that it does in the work of many contemporary artists who are utilizing beauty today.

As I see it, beauty is a subject that will continue to be contested and debated in the next decade and beyond. Meanwhile, I bet my money on the Trojan Horses, works like those of Basher and Lipps, wherein formal beauty lines up with their conceptual and cynical framework.