Cyprien Gaillard. “Desniansky Raion,” 2007. Video with sound, 30:00 min. © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy Bugada & Cargnel, Paris.

One would be hard-pressed to find a more memorable video than Cyprien Gaillard’s Desniansky Raion (2007), currently on view in MoMA PS1’s The Crystal World—the first solo museum exhibition of Gaillard’s work in New York. The three-part video opens with a static establishing shot of Genex Tower, the colossal, Brutalist style building in Belgrade, Serbia, whose twin concrete towers are connected near the top by a bridge-like structure and capped with a bizarre rotunda that once housed a revolving restaurant. The video (a segment of which you can watch here) then cuts to a parking lot of a drab housing complex in St. Petersburg, Russia, where we witness two large groups of men—one mostly wearing red shirts and the other blue—slowly walking towards each other. Set by Gaillard to the hypnotic electronic beats of French composer Koudlam’s “I See you All,” the video shows the color-coordinated groups marching in loose formation, reminiscent of ancient armies confronting each other on some distant battlefield. Suddenly, signal flares billowing smoke arc through the air and the two groups come together, clashing in flurry of fists—a breathtaking display of raw physical violence set against the stark backdrop of the housing block. As the sounds of Koudlam’s pulsing music draw louder and more urgent, the furious hand-to-hand combat intensifies while bodies of the fallen lay strewn on the pavement. Before long, the blue faction beats a hasty retreat, only to regroup moments later on one side of a nearby pedestrian bridge. The two sides come together again, this time clashing on the impossibly narrow span of the footbridge. The blue group is once more chased off, and the victors in red erupt in victorious celebration.

Cyprien Gaillard. “Desniansky Raion,” 2007. Video with sound, 30:00 min. © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy Bugada & Cargnel, Paris.

The video footage used by Gaillard, who was born in 1980 in Paris and currently lives and works in Berlin, documents a subculture of fight clubs that have sprung up in suburban housing projects in and around St. Petersburg, Russia. As the exhibition reveals, these and other modernist housing blocks found across the Western world are a recurring motif in Gaillard’s work. Ubiquitous in the post-war era, such housing structures once embodied modernist notions of community but soon became viewed as architectural eyesores and deemed unsuccessful experiments in high-density public housing on account of the crime and other problems associated with them. As structures embodying the failed utopian aspirations of modernist avant-garde thought, these public projects have become the quintessential monument for Gaillard’s purposes (one of the artist’s early video projects not on view at PS1 deals with Pruitt-Igoe, the 1950s urban housing project in St. Louis, whose demolition in 1972 signaled for many the end of Modernism).

As one watches Desniansky Raion, the housing block that forms the backdrop for the raw violence that unfolds before it transforms from a noble symbol of utopian values to one of social division and alienation. But what makes Desniansky Raion particularly compelling is that as one watches it it becomes clear that Gaillard isn’t simply re-litigating the impact of modernism in some overtly ironic commentary on its ethical and aesthetic value. Instead, the artist’s anodyne presentation of this ruined monument to modernist promise set to dance-hall-style music becomes an oblique meditation on how certain artifacts from the past continue to function in the contemporary moment in unforeseen ways. Indeed, while any grand sense of community and togetherness encoded in the stark modernist façades disintegrates not long after the first flares hit the ground and the fists begin to fly between the rival gangs it also becomes apparent that such ideals may in fact endure, reconstituted and perverted into complex tribal formulations of fellowship and affiliation.

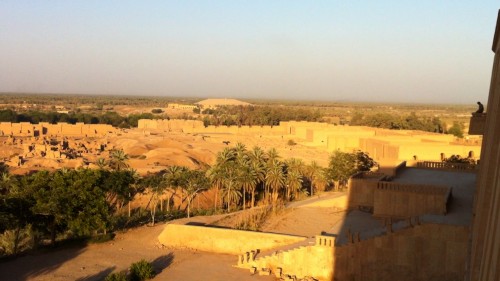

Cyprien Gaillard. “Artefacts,” 2011. HD film transferred to 35 mm, continuous with sound. © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin London; Bugada & Cargnel, Paris; and Laura Bartlett Gallery, London.

As Desniansky Raion and the other works gathered in this exhibition make clear, Gaillard’s main preoccupation is with the complex relationship that exists between the historical past and contemporary reality. In his film Artefacts (2011), for example, footage of the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon is interspersed with scenes of US soldiers in modern-day Iraq; imagery of archeological artifacts forlornly lining the halls of Iraqi palaces and museums; and a shot of the modern-day reconstruction of Babylon’s legendary Ishtar Gate in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum. Loosely connecting ancient history to modern-day reality, Artefacts loosely thematizes the ceaseless cycles of empire, the romantic preservation and reconstruction of the past in reality and in our popular imagination, and the complex bearing of history—and our conception of it—on current events (a point made by the suggestive title of another work on view in the exhibition: Real Remnants of Fictive Wars). As such, Gaillard’s approach represents a turn away from a typical line of thought in which historical perspective is marked by a clear demarcation of present from past. Rather, the artist considers the seemingly impervious veneer of the present to be transitory and precarious, repeatedly marked by eruptions and reformulations of historical forms and impulses yet seemingly lacking any sense of clear causality or purposeful progress.

Cyprien Gaillard. “Artefacts,” 2011. HD film transferred to 35 mm, continuous with sound. © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin London; Bugada & Cargnel, Paris; and Laura Bartlett Gallery, London.

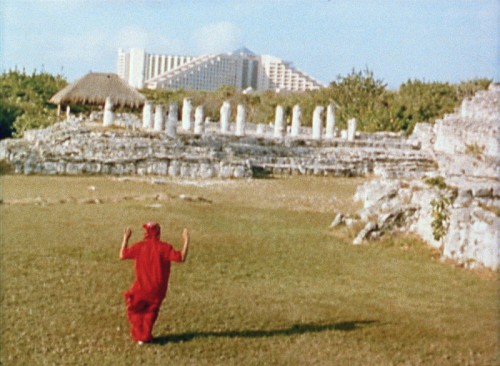

It is a point driven home by Gaillard’s video Cities of Gold and Mirrors (2009), a montage of images from Cancun, Mexico in which shots of Mayan ruins are juxtaposed with college-age kids partying outdoors, scenes from a night club, local mega-resorts designed to resemble ancient Mayan temples, and a masked member of the Bloods gang, dressed in all red, dancing and flashing gang signs atop the El Rey Ruins, a Mayan archeological site located immediately adjacent to a hotel golf course. The work’s title alludes to The Mysterious Cities of Gold, an animated TV series from Gaillard’s childhood that centered on the adventures of a young Spanish boy named Esteban in search of lost pre-Columbian cities in the New World. And with its occasionally romantic treatment of certain subjects (the gang member’s ritualistic dance is shown in slow motion and it is achingly beautiful) Gaillard’s video, originally shot on 16mm film, often has the feel of a far off dream. But with the inclusion of images of the kitschy culture industry that has sprung up around the Mayan ruins and stark reminders of Cancun’s reputation as a popular spring-break destination, Cities of Gold and Mirrors becomes a meditation on how reality rarely comports neatly with the cultural fantasies and memories that fuel it (the city of Cancun was, I was surprised to learn, only founded in 1970 as a tourist destination).

Cyprien Gaillard, “Cities of Gold and Mirrors,” 2009. 16 mm film, color, with sound. 8:52 min. © Cyprien Gaillard. Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin London and Laura Bartlett Gallery, London.

Filled with scenes of latter-day ritual, destruction and contradiction, Cities of Gold and Mirrors foregrounds Gaillard’s concern for the ways in which history functions as a hall of mirrors, its complex layers forming and informing the present while simultaneously being subject to revision, reformation and re-contextualization. Fittingly, a concluding shot of the video is of a building in Cancun whose modern, mirrored façade shudders ever so slightly as unseen demolition charges detonate inside the reflective structure just before it implodes into a cloud of dust and debris.

Gaillard’s interest in the intricate and unpredictable relation between historical and contemporary sites is further evident in a series of non-video works presented in display cases, in which the individual teeth from the bucket of a large industrial excavator machine are exhibited like precious pre-modern artifacts. Fetishistically presented on high pedestals and bathed in golden light, these excavator parts, typically associated with either unearthing the past or removing the old to make way for the new, embody the tension inherent in much of Gaillard’s work between cycles of creation and destruction, between history and its reinvention.

Installation view of “Cyprien Gaillard: The Crystal World” at MoMA PS1, January 2013. Photo: Matthew Septimus

In conferring upon these objects the status of precious relics, Gaillard raises broader questions concerning cultural value and memory, and the determining forces behind what we choose to preserve or demolish and remember or forget in the name of progress. For Gaillard, the relationship of the present to the past is one of constant transition and merging manifestations. And as this exhibition makes clear, he does not harbor wistful longings for some lost authentic experience but rather an intense recognition of the complex bonds and muted legacy of our cultural inheritance. [1]

Cyprien Gaillard: The Crystal World is on view at MoMA PS1 through March 18, 2013.

[1] The title of this essay was inspired by Thomas C. McEvilley’s book Sculpture in the Age of Doubt. New York: Alworth Press, 1999.