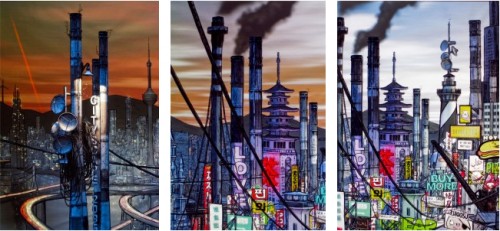

Yannick Jacquet aka Legoman and Marc Ferrario aka Mandril. “Cityscape 2095,” 2013. Courtesy of the artists.

Artists today program forms more than they compose them: rather than transfigure a raw element (blank canvas, clay, etc.), they remix available forms and make use of data. In a universe of products for sale, preexisting forms, signals already emitted, buildings already constructed, paths marked out by their predecessors… –Nicolas Bourriaud, 2001

In my fourth and final post covering New Frontier at Sundance 2013, I explore the creative and innovative exploration of augmented space—which refers to technologies, objects, or symbols that overlay physical space with information. It is a new type of collage that makes use of a broad collection of forms and techniques. Keiichi Matsuda provides a good starting point from both technological and aesthetic perspectives.

[Augmented Space] is a paradigm that succeeds Virtual Reality; instead of disembodied occupation of virtual worlds, the physical and virtual are seen together as a contiguous, layered and dynamic reality. –Keiichi Matsuda

Augmented space is a method of creating a space within a space, or merging two or more dimensions in a single artwork. In his essay Postproduction (2001), Nicolas Bourriaud explores the mashup of images that contemporary artists project onto walls, or overlay on physical surfaces as a framework for innovative forms and narratives. In Datamosh (2011) Yung Jake layers compression artifacts and technology as a form of art. Cityscape 2095 (2012) is the result of a collaboration between Yannick Jacquet (aka Legoman), Swiss illustrator Marc Ferrario (aka Mandril), and sound designer Thomas Vaquié. These artists merge multiple dimensions by showing the passing of a day in fast-forward using drawings, video projections, and sound. Cityscape 2095 puts the spectator at the summit of a tower facing the horizon.

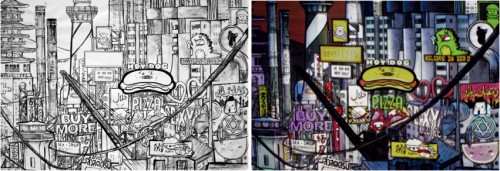

Imagine being on the observation deck of a tall skyscraper, looking out over the city below. Jacquet/Legoman and Ferrario/Mandril use a mixture of architectural influences to co-author an urban text that feels strangely familiar but is also impossible to locate. It is a representation of the artists’ utopia—a futuristic world within the real world, or a physical space augmented by the virtual. The idea was to show the passing of a day in an imaginary city in fast-forward. In the early hours of the day, the scene is sparse and line-based; but, as time passes, the imagery grows until it becomes urban semiotic overload—a desert of the (physical and hyper) Real.

View of “Cityscape 2095.” Courtesy of the artists. Photo by Legoman.

Cityscape 2095 brings to my mind the layered drawing techniques and artworks of Julie Mehretu and Matthew Ritchie, with the virtual reality set design of Cao Fei.

Creating a work of art can include additive techniques (building up layers of marks, paint, or materials) and subtractive methods (erasing, removing, or hiding elements that compose the work). Julie Mehretu often adds and removes visual information as she creates her drawings and paintings. The artist refers to elements of mapping, architecture, and atmosphere in her artworks… Mehretu discusses how she constructs her artworks, adding and subtracting layers of abstracted imagery. –Art21, Thematic: Addition and Subtraction

Top: Julie Mehretu. “Auguries,” 2010. Courtesy John Berggruen Gallery; Bottom: Matthew Ritchie. “Proposition Player,” 2003. Courtesy Andrea Rosen Gallery.

Mehretu’s works are not electronic or digital but they suggest possibilities for the merging of physical and abstract layering with electronic layering (augmented space). The animation of Mandril’s drawings in Cityscape 2095 is similar to the moving wall drawings displayed in Matthew Ritchie’s Proposition Player (2003). In Cityscape 2095, Mandril applies ink, watercolors, and wash techniques to enhance and mask Jacquet’s 3D modeling. Mandril, Mehretu, and Ritchie explore the boundary between abstraction and figuration by working between different states, using layers to create an illusion of movement and of time passing.

Legoman and Mandril. “Cityscape 2095 (details),” 2013. Courtesy of the artists.

Yannick Jacquet’s 3D visuals reminded me of work by Blade Runner visual futurist Syd Mead, Cyberpunk 2077 video game art, Michael Arias’ feature-length Japanese anime film Tekkonkinkreet (2006), or RMB City in the virtual world of Second Life, planned and developed by the artist Cao Fei.

Left: Cao Fei. “RMB City,” 2008. Courtesy of the artist; Middle: “Cyberpunk 2077,” 2013. Courtesy of CD Projekt RED; Right: “Tekkonkinkreet (production still),” 2006. Courtesy of the artists.

RMB City is a condensed simulation of contemporary Chinese cities. Cityscape 2095 is a ‘world city’ where each country’s own visual identity clashes with the others. Much like the postproduction process of Tekkonkinkreet, the 3D modeling of Cityscape 2095 is enhanced by animation and hand drawing. Jacquet and Mandril push creative expression and experimentation in ways that transcend physical reality. They create a portal through which viewers can experience their imaginary ‘world city.’ By overlapping urban narratives and geographies, the architecture becomes embedded in abstraction: the fast food restaurants, department store windows, billboards, and so on, are discordant in a interesting way.

Legoman and Mandril. “Cityscape 2095 (details),” 2013. Courtesy of the artists.

In Cityscape 2095, the physical and virtual are seen together as a contiguous, layered, and dynamic reality. The artists use projection mapping (or “2D mapping“)—a technique where video projectors overlay virtual content onto physical objects. By carefully aligning the projected virtual content with the physical objects, a variety of effects can be accomplished. Visitors observe the continuous change and movement of an augmented landscape—this is Lev Manovich’s idea of augmented space. Here, the spatial and information layers are equally important because the artists treat space as a visual text to be read and interpreted by the viewer, capturing the poetics of augmented space and creating a utopian/dystopian world of the future.

Legoman and Mandril. “Cityscape 2095,” 2013. Courtesy of the artists.

In his travelogue, America (1986), Jean Baudrillard created a representation of the country that included the Wild West, jazz, the deserts of the Southwest, the neon lights of motels on Route 66, graffiti, and more. Baudrillard saw America as a glittering emptiness—a savage, empty non-culture—in short, as the purest symbol of the hyperreal culture of the postmodern age. I began this series with Baudrillard, so it made sense to end with his vision, as an arts writer in search of the simulacra of reality—a new ethos in contemporary art that expands our imaginations of how architecture and physical artifacts can use new media.

Pingback: Art 2.1 | New Frontier at Sundance 2013: The Compilation « SL Art HUD Blog Thingie:

Pingback: 2013: A Year in Review | Renegade Futurism