Dodge Ram website (February 2013), with overlaid indicators of signifiers of print used in their marketing campaigns.

A few weeks ago I traveled from Chicago to New York to sit on a College Art Association (CAA) Southern Graphics Council International affiliate panel organized by Printeresting.org co-founder Jason Urban on the subject of “Reproducing Authenticity.” Three fellow print enthusiasts (Beauvais Lyons, Lauren van Haaften-Schick, and Lisa Bulawsky) and I examined the evolution of printmaking in the twenty-first century, and attempted to grapple with “the visual language of print as a signifier of authenticity and the complex relationship of real printed matter to its life in the virtual world.”

For those of you who didn’t make it to CAA this year, here are some excerpts from my paper titled Studio, Museum, Screen: Print & the Virtual, Authentic Image—thoughts on the intersections of printmaking and the digital image, and the subsequent constructions of an authentic image online. You can take a peek at a wide range of supporting images in my slideshow here.

————————————————————————

A digital image of a work of art is composed of three things: a collection of mathematical data; a signifier (or placeholder) for a real, physical object; and a signifier for (or reminder of) the artist who has created that object. For the viewer, digital images act as the point of connection between object and artist, yet a backlit collection of data on the screen lacks presence. The result is an unconscious hunger for substance, truth, the genuine: a desire for what some might call authenticity.

This phenomenon was anticipated by the philosopher Walter Benjamin in his seminal essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936), in which he expressed his concern that in the modern age of mechanical reproduction, the work of art would lose its “authenticity” or “aura” (he uses these two terms almost interchangeably). His point is equally valid in today’s virtual environment: the authenticity/aura of the work of art is what suffers in the age of digital reproduction.

So, what exactly is meant by the term “authenticity” in this revisionist context? There are many variations on the word—for instance, we often assume authenticity (or authenticating) to come from an institutional, authoritative source. To simplify, the basic concept of authenticity (as set forth in the Oxford English Dictionary) is that someone holds the opinion that another person or thing is “entitled to acceptance.”

Why is this even worth discussing? Well, for one, we tend to throw the word authenticity around quite a lot. “Authenticity” today is a buzzword, a false word that means a subjective kind of truth. When we call something authentic (another person, for instance, or a product), that judgment lies just as much in the person making the claim, as it does in the object. We seem to use the word to outwardly legitimize the power of our individual opinions.

As a result, the word as we use it today is often controversial, opinion-based, and imbued with anxiety and moral undertones. (See, for example, last year’s hullaballoo over pop singer Lana Del Rey’s apparent lack of authenticity, as Sasha Frere-Jones addressed in the New Yorker.) As literary critic Lionel Trilling argues in Sincerity and Authenticity (1971), “that the word has become part of the moral slang of our day points to a peculiar nature of our fallen condition, our anxiety over the credibility of existence and of individual existences.”

Rather than addressing the authenticity (or provenance) of an object (e.g. did Matisse paint a particular portrait or not), my main interest lies in the authenticity of the images that represent said object. If (in rewriting Benjamin) the authenticity/aura of the work of art is what is lost because of digital reproduction, it is fascinating to consider what have become twenty-first century solutions to this problem—how we have managed to maintain (and even enhance) the authenticity of the digital image.

Signifiers of print evident in clothing advertisements (ink splatters and distressed surfaces, faux wood type, etc).

PRINT, ADVERTISING, & THE VIRTUAL, AUTHENTIC IMAGE

What, then, does entitle a digital image to acceptance? Strangely, printmaking plays a unique role in today’s digital environment as an “authenticating” force in the virtual world. Because we lack a sensual connection to the flat, backlit screen-image, we compensate for it by seeking out things that have some relation to real, natural materials, like those used in printmaking (wood, metal, cotton, ink). This points to a trend in twenty-first century art related to what Michael Sanchez has coined “screen povera,” the evolution of the senses-provoking arte povera of the late 1960s. (“Contemporary Art, Daily” in Art and Subjecthood: The Return of the Human Figure in Semiocapitalism, 2011). Amidst an avalanche of reproducibility, it is images connected to physicality, craft, and the handmade that invite our tired eyes to rest.

Signifiers of print evident in food/grocery websites like Trader Joe’s (ink stamping, brown paper, letterpress type elements, wood grain, etc.)

These “signifiers of print” (e.g. scans of natural materials, ink splatters, letterpress or wood type, Ben-Day dots, CMYK off-registered colors, etc), many of which can be seen, for example, in the 2011 Dodge Ram ad campaign, shown at the top of this post, serve as placeholders for the authenticity of an image. In other words, using aspects of printmaking in design elements on websites and in advertisements means we (as the viewers) are more likely to accept the product or image. Signifiers of print make an image (and product) “entitled to acceptance.”

Signifers of print evident in 2012 op-ed illustrations (Ben-Day dots, plate marks, distressed or off-register edges, etc).

This of course begs to be capitalized upon. Advertisers, web designers, and individual users co-opt specific images related to print for unrelated economic ends in ads for products like automobiles, alcohol, clothing, and food, as well as “selling” journalism. (For more examples see my slideshow.) By utilizing these print signifiers, advertisers are pointing to authentic-by-association products entitled to economic acceptance. The digital salesman is able to capitalize on the borrowed history of printmaking, to claim authenticity without working for it.

THE MUSEUM & THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE INSTITUTIONALLY AUTHENTIC IMAGE

Another solution to the loss of authenticity/aura in digital reproduction lies in the construction of an institutionally “authentic image.” While it may be an oxymoron to talk about an authentic image in light of Benjamin’s theories, in the twenty-first century it is an inescapable fact that we primarily rely on digital images (particularly in the art world) to provide us with information about an object. Given this reliance, there is a need, and a growing market, for digital images that adequately reproduce a work of art. This need is user-driven (e.g. researchers, museum visitors, publishers), but also museum-driven, for an increasing number of museums (such as the Tate and the Walker Art Center) consider their online presence as an institution in itself.

Just as authenticity is subjective, and able to be manipulated, so is the authentic image of a work of art—dependent on camera, lighting, editing, file type, screen calibration, browser, etc—which poses huge hurdles for scholarly inquiry. Museums, where authority is granted by institutional context and supported by scholarly research, own the artwork displayed online, and present (often on collection websites) an ostensibly authentic digital copy.

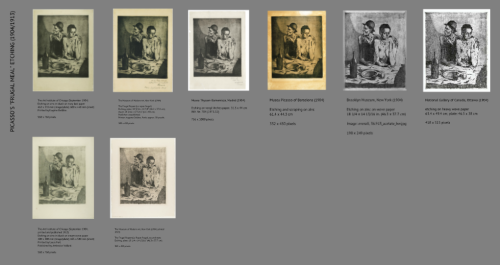

Comparisons of the varying qualities of images for Picasso’s “Frugal Meal” etchings as held by six different institutions.

This image authenticity is called into question when virtually comparing multiple prints from the same edition. As I have found, prints that should look the same in person are often displayed entirely differently between a range of museum collection websites—see, for example, a comparison of Picasso’s 1904 Frugal Meal etchings at the Art Institute of Chicago; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid; the Museu Picasso, Barcelona; the Brooklyn Museum; and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. The veracity of the image (its actual color, paper, plate tone, etc.) becomes flexible when presented with a high-resolution image from one museum, versus a low-resolution thumbnail offered by another. With no imaging standard in place, it is impossible to even approximate an authentic image.

An examination of Picasso’s 100-etching Vollard Suite (1930-37) offers another excellent example of the confusion that ensues when comparing prints between collections. Picasso’s groundbreaking edition is only owned in its entirety by a very small number of institutions, and is rarely exhibited all together (thus further denying physical, in-person comparisons). The online archives of the institutions that do own this work do nothing to facilitate a greater understanding of the suite. The British Museum’s online collection (the recipient of a recent gift of the Vollard Suite, and host of an exhibition of such in 2012) lists object records but offers no images, a practice mimicked by the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, and the National Gallery of Canada. The sites for other institutions (e.g. the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth; the National Gallery of Australia) offer only small thumbnails.

IMAGING SOLUTIONS: IMAGEMUSE

The wide disparity between quality of digital images across museum collections can be frustrating for researchers, making it difficult, if not impossible, to compare prints from the same edition. As I was informed by Christopher Gallagher, Director of Imaging at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC), museums are aware of this problem and there has been a major push over the last five or six years to normalize imaging standards between museums through an organization called ImageMuse.

A 3-D photography room in the Imaging department at the Art Institute of Chicago. Photograph by the author.

Founded by six enthusiastic museum staff members from different institutions in 2007, “ImageMuse pose[s] questions and offer[s] solutions regarding cultural heritage imaging workflows,” and it now counts among its members over 300 institutions throughout North America and Europe. The technicalities of imaging, and the narrow nature of the ImageMuse audience has meant that their research and developed standards came into existence without much attention from the scholarly and academic realms. A 2010 benchmark study from the Rochester Institute of Technology confirmed that ImageMuse’s photographic standards for file capture, input, and sharing (called UPDIG-DISG) represent the best practices for digital images at major arts institutions. With such exhaustive standards now in place, lighting, Gallagher notes, is really the last avenue for artistic license. Over time, this will result in standardization that will allow researchers to compare “apples to apples.”

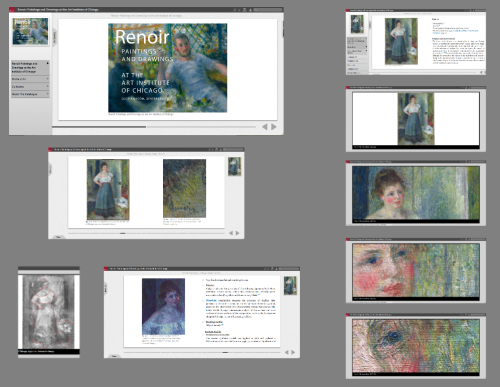

The Art Institute of Chicago’s Online Scholarly Catalog Initiative Renoir pages, showing a sample object entry, with high resolution photography, including UV and X-ray images.

How, then, are ImageMuse standards being implemented within a museum context? Beyond the technical details of photography and digital file standardization, an aspect of Gallagher’s and ImageMuse’s efforts that offers intriguing possibilities for the future of art historical publication is the Getty-funded Online Scholarly Catalog Initiative (OSCI). OSCI is a five-year, joint effort between nine arts institutions that “aims to transform how museums disseminate scholarly information about their permanent collections to make it available through web–based digital formats.” For more detailed information, see the Getty’s interim report.

The Art Institute’s OSCI project combines new curatorial and conservation research, focusing on their substantial holdings of works by Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. To date, you can examine a few sample catalog entries in detail online, with high-resolution photographs (including images shot using natural daylight, X-ray, and UV-light technologies).

Beyond the use of high-res images, another innovative aspect of these online publications is that, like printed publications, they are meant to be presented in a final state of research, and (unlike more frequently-updated collection interfaces) the published website data will never be altered again. As such, these digital publications will be imbued with the academic authority generally reserved for printed materials (catalog production and publication), lending authenticity to information presented in this digital format. As such, OSCI standards will place these artworks and research within the realm of scholarly discourse, entitling them to academic acceptance.

As Benjamin anticipated, and I hope to have shown, because authenticity (and the aura) is a subjective concept, it is not actually possible to reproduce. Yet, reproducible visual elements like the signifiers of print enable the construction of authenticity online, and high resolution imaging technology has begun to enable the closest possible approximation of an authentic image. It is impossible to know how long print will remain the catalyst for virtual authenticity, or how long it will take for high quality image standardization to become the norm, but it is exciting to recognize the ways in which the analog still informs the digital. I am hopeful that elements of print, and printmaking, will continue to inspire new innovations in digital publishing, artwork, and design.

————————————————————————

Guest writer Julia Vodrey Hendrickson is an art critic, historian, and a visual artist. In 2012, she received her MA in the History of Art from the Courtauld Institute of Art, London, completing a thesis on the gendered histories of decorative wallpaper and the evolution of the modernist white wall. Julia has published her writing in the California Printmaker, Chicago Reader, Art In Print, Printeresting, Newcity, and Bad at Sports. She is currently the registrar and publications manager at the Chicago gallery Corbett vs. Dempsey.