Xerox: Barbara T. Smith 1965-1966 is an extensive exhibition of early xerographic work by the eponymous artist. Largely comprised of self-published, one-of-a-kind books, the show happened to open at The Box Gallery in Los Angeles the same weekend as the LA Zine Fest, and in the same month as the city’s first art book fair. Many of the pieces on view had been in storage for some 50 years; they offer a generously personal glimpse of Barbara T. Smith’s work at an extremely charged moment in her life—the end of her marriage and beginning of a major shift in her career.

The works in Xerox parallel Smith’s personal story, starting in 1965 when she set out to make a lithograph, a transfer of a gravestone rubbing onto a lithography stone. “I wanted to press a real, oily daffodil against the litho stone,” she said in a recent interview. “The resulting print would be a stone sandwich with a sprouting flower between.” The project was politely rejected by Gemini G.E.L. lithography shop, then newly opened, on the grounds that they were busy working with Josef Albers. Feeling the fury of rejection, Smith decided to set up a copy center, anchored by the newly invented Xerox machine, in the dining room of her Pasadena home:

“I told myself lithography [was] in any case obsolete. It [was] merely the printmaking media of the nineteenth-century. We [were] in the twentieth-century and logically the print media of our era would be the business machine! I set out to discover which types were technically innovative. Xerox won. The ink was not ink but ‘toner,’ a bead of plastic material that becomes electrically charged as the light scans the images and it falls on the paper replicating the pattern and density of what it is reproducing. There it lays like dust until the paper passes through a heating element where it is sintered or fused to the paper. There the bead loses its integrity and bonds in a completely new way with the paper. The heat is just low enough to keep from setting the paper afire. Occasionally, fires would erupt and I was told to never mind, it’s part of the process.”

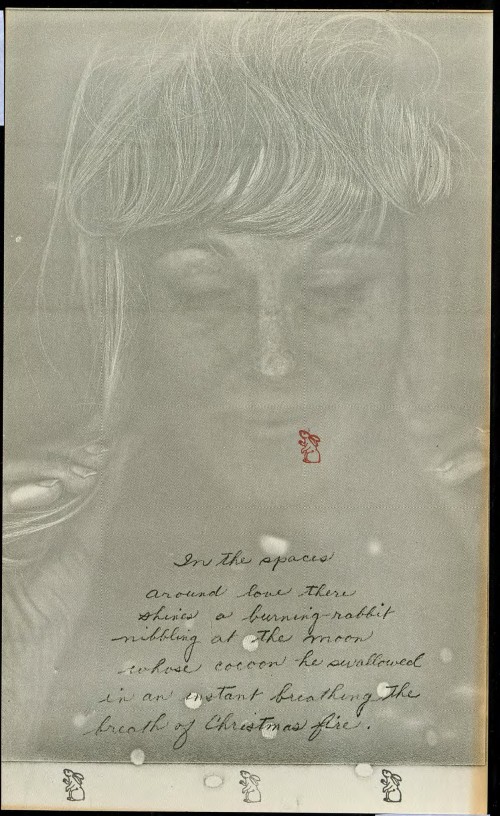

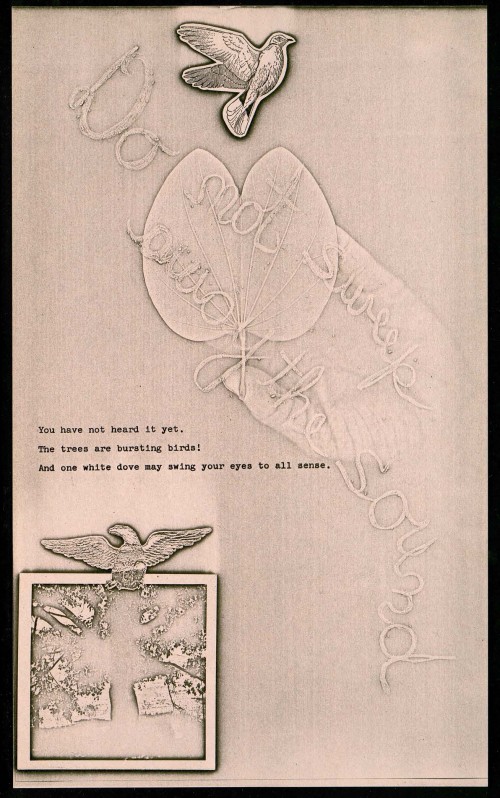

At a time when many women in her station were trying to bust out of the constraints of domesticity, Smith experienced explosive liberation in her home, working long hours with a leased Xerox 914 machine for eight months. She experimented with films, papers, and processes such as double printing—feeding the machine transparencies that would melt in its mouth. On the plate of the machine, she made direct photocopies of her body and her children’s faces. She xeroxed family photographs, roses, pantry staples such as flour and rice, odd-lot household items, lipstick smears, and wartime periodical clippings, combining all of these elements with poetry she wrote between 1960 and 1963.* (Smith refers to this period as one of personal and spiritual breakthrough.) Other forms of portraiture began to play a role after she enlisted the help of fellow artist and photographer Jerry McMillan whose studio was nearby. He photographed Smith, her son, and two daughters, producing images that Smith obsessively reproduced in many different compositions.

Simultaneous with the family portraits, Smith staged playfully sexual interactions, unfurling her hair over the Xerox machine and pressing her breasts and pubic mound directly to the glass plate, leading to pieces like Oh! those Leopard Skin Bikinis (Coffin) and Where Did You Get That Polkadot Blouse (Coffin).

Barbara T. Smith. Bottom: “Coffin: Oh! Those Leopard Skin Bikinis,” 1965-1966. Xerox print book. Courtesy The Box.

In a statement accompanying Xerox the artist writes:

“I had fantasies of making very erotic imagery which could naturally play into lovemaking as well with my husband. Although we could not simultaneously get on the glass plate, we could take turns and have our genitals transferred as image to paper, by running the papers through twice. Thus a whole range of possible images could be made. I was pushing the edge of the culturally permissible and certainly the edge between my husband and myself. If this boundary was dropped, no telling where it would take us, but it certainly would take us if we did this together. Unfortunately he said no. So I continued alone. It was odd however that it seemed quite all right to him that I [had] made these transgressive images, which sat about the dining room where visitors could casually see them. This made me feel violated and unprotected instead of daring because I was doing it alone. Odd that this seemed not to bother him, his wife so casually revealed.”

Smith goes on to describe her attempts to use four booklets—First Class Mail (All three children), American Standard (Katie), Mellon National Bank and Trust (Rick), and Important/First Class (Julie)—to entice her children “out of the corporate world of their father and into the life of joy, imagination, nature, play and beauty.” The booklets were made from photocopies of stock dividend statements.

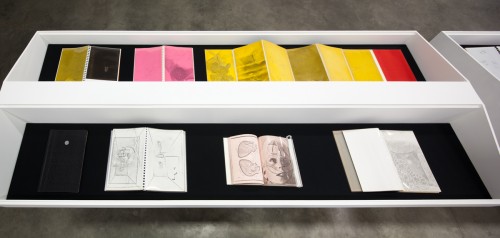

At the end of 1966, anticipating a painful separation from her children, Smith bound their portraits alongside other xeroxed ephemera in black covers, stamped each with a silver cross, and included them in the Coffins series. In 1968, Smith’s divorce was final and from then on her ex-husband repeatedly blocked her interaction with their children. After losing a custody battle in the early 1970s, she did not see her daughters for 17 years.

Barbara T. Smith. “Coffins,”1965-66. Series of Xerox print books. Individual books (left to right, top to bottom): “Time Piece, Pink Rose,” “Coming Out Party,” (closed) “A Broken Heart,” “An Awakening.” Courtesy The Box Gallery.

Several of Smith’s books at The Box, as well as her later performance works like Birthdaze, bear resemblance to 1960s Confessionalist poetry. With the help of psychotherapy and meditation Smith surfaced so-called taboo subjects. When she was able to trade works of art for Gestalt therapy with Ed Wortz, who introduced her to Buddhism in 1973, she had a “life-saving moment.”

Smith has come to view her unrealized lithograph as a symbol for the death of an era, and her xerography as the beginning of her career as a politically-engaged performer and body artist:

“My use of the naked self is, on the one hand, merely based on the curiosity of wondering about what it would look like, how it would feel, the humor of this. Secondly, the pushing beyond the boundaries of normality represents my isolation and thirdly a desire to be seen, heard, valued, inherently. We were only beginning to know that this was not only a personal issue, or a class issue but one of an entire gender. In a culture where the female voice is absent, the content of the work became coexistent with the female being and thus was inherently political as well. This thrust in my work while embarrassingly self-revealing, is that which went beyond the purity of minimalism of its time. I felt my cultural oppression, but it was difficult to grasp, especially because I was a privileged white female. And I was also schooled in the rigor of non-complaint, of using philosophy, science or religion to somehow overcome basic needy feelings and desires. To this day, the eroticism, and thus the risk of this work, was meant initially to be private but eventually has become part of the public domain because time has intervened allowing me some distance and I think they are now historically important.”

After these formative years with the Xerox machine, Smith went on to employ several emerging technologies in her work and life. She spent four and a half years building the enormous interactive fiberglass and electronics sculpture Field Piece (1972), and utilized early videophone technology to stay connected with her partner (who was living inside the early 1990s project Biosphere 2, or “the 21st Century Odyssey“) while Smith traveled the world.

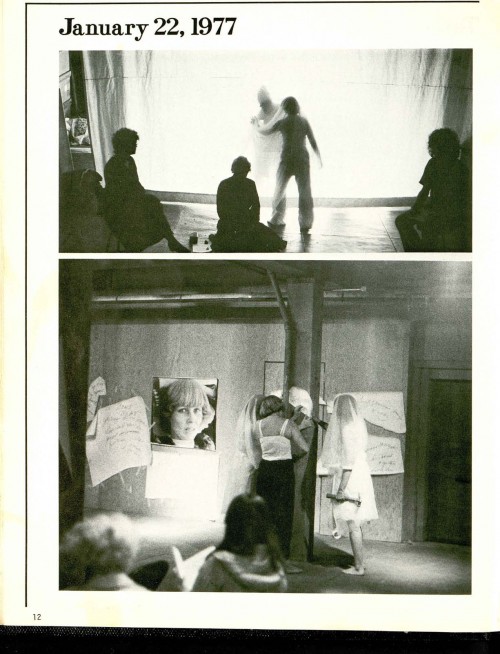

At the same time, Smith built an extensive historical record of her spiritual yet corporeal performances, documented in her early writings and photographs for the magazine High Performance.

Barbara T. Smith. Documentation of “Ordinary Life,” a performance exchange in two parts. Part I performed in a studio in Venice as part of Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art. Part II performed at 80 Langton Street, San Francisco, January. 22, 1977 and March 12, 1977. “High Performance,” Volume I, Issue I, January 1978. Courtesy Barbara T. Smith.

What these black-and white reproductions reveal today is that Smith is no longer alone in her meditations on art and life. Rather, she is in conversation with artists like Paul McCarthy and Nancy Buchanan, both ten years her junior.

“My entry into the art world was quite naïve in a way because I was older than everybody else. But it didn’t feel like it; I felt like I was the same age, because we were in the same generation of art.” When asked about the order that she created for herself, Barbara responds quickly, “I had to—that’s the one thing that held me together. It’s just that—a struggle…I’m only seeing all this now because we’re putting my archive together, and journals. I’ve been writing about my early work up until 1981—It’s a book that has to be edited. I’m seeing my life and friendships completing itself in circles, everything coming around…I’m realizing what I nutcase I was in some ways [laughs]…I’m very touched that all this is happening, that people get to see the work and it’s getting appreciated—because who knew? This is why I try to encourage young artists—don’t throw your work away. Because you start out and you’re operating almost in a vacuum, you’re just stumbling around—some more than others.”

*Copies of Smith’s poetry-xerox works are available here. All works ©Barbara T. Smith and intended for research only.

Xerox: Barbara T. Smith 1965-1966 is on view through March 23, 2013.