Introduced to Mira Schor through her writing, I first saw her work in person last year at Marvelli Gallery. A few weeks ago I had the pleasure of visiting her in her studio. The following is our post-visit email exchange centering on her recent work and ideas. In February, she participated in the Annual Artists’ Interviews series (along with Art21 artist Janine Antoni) at the 2013 College Arts Association Conference.

Amanda Beroza Friedman: You had been making text-based works for more than a decade. What prompted the injection of figuration and narrative in your more recent work?

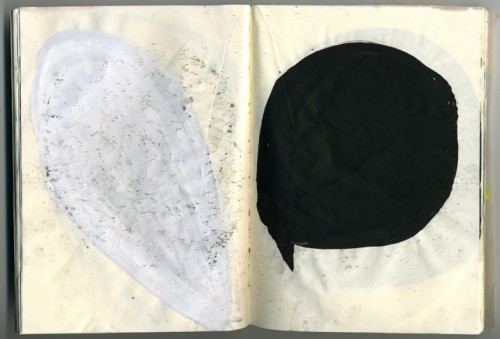

Mira Schor: The figure’s return emerged out of the work that I did when there were no words to express how I felt after a personal loss, the death of my mother in 2006. I had been working with language for about 15 years at that time. Language as image was the subject of my work from the 1970s also. Then the language was personal and autobiographical in nature. In the work from the ’90s to 2006, the language was appropriated, mostly from the news, or was related to art making itself: words like trace, sign, painting, drawing, even the word writing. After my mother died, I felt I had to start back at a kind of zero of my identity as an artist; I started with basically just a blob of black ink and that developed into the empty thought balloon. It turned out to be a great space in which to paint paint, to place paint where you expect to find language. Some of those thought balloons looked a lot like heads so I put eyeglasses on them, and then about a year later gave them a very basic body, with stick figure legs so they could start walking around and encountering the world.

Mira Schor. “Small Black Thought Bubble,” 2007. 4th spread, small brown notebook. 6 1/2 x 9 1/4 in. Courtesy the artist.

ABF: Do you see the inclusion of the stick figure as a distancing strategy? How do you think about the diagrammatic or cartoon qualities in this work? Some of the images seem to function as a type of pictorial language or as one section in a graphic storyboard.

MS: I call the figure an “avatar of self.” I’m not sure it’s a distancing gesture. It may seem that way but actually I try to express as directly as possible where I am at a particular moment: in space, literally, in my garden in the summer reading, or in my studio, and where I am in my sensations, emotions, and thoughts. The diagrammatic and cartoon aspects of the work come from the speed necessary to keep the flow between everything that I do in my work—paint, write, teach, read, draw, think—as connected and speedy as possible. In works from the early ’70s that were more specifically figurative, I represented my figure and the space where I was with more detail and fullness though not in an academic manner, more in the representational vein of Florine Stettheimer for instance or Rajput painting. Now the cartoon and diagram modes allow for the co-existence of figure, landscape, and language without any need for the niceties of representational rendering.

ABF: Could you speak to your recent and ongoing body of work, the Fallow series? I notice the inclusion of a horizon line as a distinct factor in their composition.

MS: I always was fascinated by the concept of leaving a field to lie fallow so that it could regenerate for future cultivation. I learned about it in grade school and when I was an artist in my twenties I thought about it a lot, because as I learned what kind of artist I was, including the rhythm of how I work, I was terrified that if I stopped making art for a minute in order to regenerate, I might not start up again.

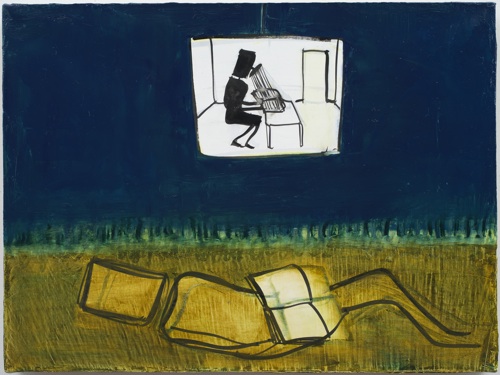

Mira Schor. “La Cigalle et La Fourmi,” 2012. Ink and oil on gesso on linen. 12 x 16 in. Courtesy the artist and Collection of Clyde Beswick and Jason Chang.

Recently, the concept of lying fallow was brought back to me by Silvia Federici’s discussion, in her amazing book, Caliban and the Witch, about the tradition of the commons and other folk experience-based crafts and practices that had developed in the medieval period and that were forcibly, often violently eliminated and suppressed as part of the development of early capitalism. Each summer I choose a few books to read from beginning to end. In the winter I’m too busy to have the concentration for that kind of reading or to do work from it. I choose books that help me to confront ideas in art and culture that are or seem to be antithetical to my own practice. The summer of 2012 books were chosen to help me understand the socio-economic situation we’re in, of austerity, income inequality, and the death of the social contract that existed at least as an ideal up until the end of the 1970s. I read Federici’s book, as well as Maria Mies’s Patriarchy & Accumulation on a World Scale, and Zygmunt Bauman’s Liquid Modernity.

Caliban and the Witch is fantastic, one of the most interesting books I’ve read in years. I had been doing paintings that depicted my avatar lying in a lawn chair under a tree reading and looking up at cartouches hanging from the tree limbs representing thoughts suggested by my readings. This summer I looked at the grass that that figure lay on as the borderline between life above ground and the earth below as a generative field, so I placed my figure in the earth below the grass as a line of demarcation. The figure has her book with her as she lies in the earth, and she sometimes dreams of the space above, the space of winter work, the classroom, the computer, as in the painting La Cigalle et la Fourmi, another allegory of work and creativity that I learned in childhood.

Check back tomorrow for the second half of Friedman’s interview with Schor.