If you are even remotely interested in how everyday materials can become bizarre and (sometimes) brilliant sculpture, there are three shows ready and waiting for you in New York’s Chelsea galleries: Nayland Blake’s What Wont Wreng at Matthew Marks; B. Wurtz’s Recent Works at Metro Pictures; and Mark Dion’s two-floor delight titled Drawings, Prints, Multiples and Sculptures at Tanya Bonakdar. In all three cases, viewers (especially contemporary art educators) are treated to new works by artists who are playful with their materials and simultaneously manage to teach us about the issues and concerns that drive their work.

Nayland Blake’s exhibit greets viewers with a vinyl poster of himself—donning a leather cap and harness, black sunglasses, and his signature beard—presented under the name of “The Spectre.” The handful of sculptures and installations on view actually have enough space in the tiny gallery for viewers to examine how Blake incorporates themes of gender, identity, and community in his work as “a modern-day flaneur.” And like any good sculptor, his work invites you to look into vs. at it. I found myself walking around and around works such as Buddy, Buddy, Buddy and Oh, both standouts because of simple layering that allows for a constant mind-game of associations.

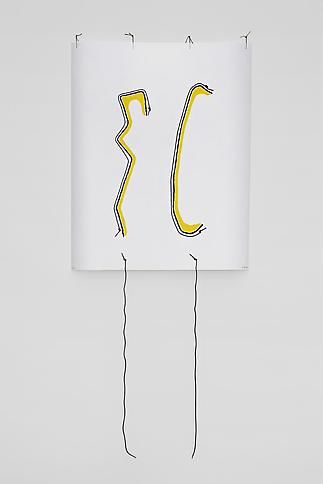

B. Wurtz’s Recent Works is certainly, as the press release states, “a delicate balancing act of configuration.” Ordinary materials come together in ways that don’t necessarily try to reimagine the objects, but rather emphasize them, the way they are joined, and how they exquisitely worm their way into space. The freestanding straw sculptures and shoe lace drawings had me thinking a lot about how we might teach sculpture in ways that go beyond the traditional and the expected without getting into bad “projects” involving pipe cleaners.

Finally, Mark Dion’s new exhibit is a treat for anyone familiar with his work. The installation holds surprises for those who examine the work carefully and actually want to linger instead of trying to see a dozen shows in two or three hours. Dion’s work is in many respects much different from that of Wurtz and Blake—especially when it comes to his driving investigation of “history, knowledge, and the natural world”—though his sculptures find ways to teach us about the world through the elements he assembles and the way he guides our viewing. Like Wurtz and Blake, Dion’s work is sometimes infused with humor, an entry point that get us to slow down. On the first floor of his exhibition, I laughed out loud at Marine Invertebrates, a vitrined sculpture of “everyday household objects” (although I must admit that describing sex toys as “everyday household objects” is a bit of a stretch). In the end, the work does exactly what it’s supposed to do, or one of the things it’s supposed to do—it gets us to reconsider the way we see relationships between forms and how we classify things. Upstairs viewers are treated to a huge selection of drawings, prints, and photos that build on the three-dimensional works, and also inform Dion’s large range of projects. Looking closely at his drawings, especially, allows for deeper understanding into how Dion plans and executes his ideas.