Mira Schor. “Expropriation Series: I’m Glad to See You Are Keeping Busy,” 2012. Ink and oil on gesso on linen, 24 x 28 in. Courtesy the artist.

ABF: Can you talk about your other recent body of work, the Expropriation series? In our discussion these works came up in connection with Federici’s argument on how we got to our current state of the triumph of global capitalism.

MS: In those works the figure is not resting in the earth of her own volition, she’s been thrown there head first. Expropriation surrounds us, whether it’s corporate downsizing, unemployment, climate-caused displacement, or expropriation of bodies of knowledge that are deemed obsolete. In one painting, painted at the peak of Hurricane Sandy between 7:30 and 9PM on the night of October 29, 2012, the figure had landed head first in the earth pitched down from a stormy dark sky. A cheery snarky little caption reads, “I’m glad to see you are keeping busy.” I was using appropriated language, quoting verbatim a haplessly condescending comment a former student wrote me in an email this winter.

ABF: We spoke about the possibility of painting paradoxically, defying commodity culture because of its specific relationship to time. I often think about how paintings can exist in their own time.

MS: Painting is always under attack, as a prime example of art as commodity and an exemplar of the modernist idea of the autonomous artwork. And most of us are conditioned by media to prefer movement. I often talk about the idea of the displacement of pictorialism, the way the exact same area of wall space that might previously have been occupied in a museum by a large painting, let’s say Courbet’s The Studio of the Painter or his Funeral at Ornans, is now the site of the same-sized projection of a video. There’s image, narrative, pictorialism, the only difference is motion, sound, and the specific time of the particular video. However paintings also contain time. In fact at best they contain time in a way that opens up contemporary time and defies spectacle. It is not Fordist time of the minute by minute, digital time of the microsecond by microsecond, it is the layered time of your experiencing it through vision and your relation to it in space. That experience contains, whether you’re consciously aware of it or not, the time of the painting’s making, the time of its layers, edges, and surfaces. A painting can open up time, liberate it—when you paint or when you look at a painting. That’s the time I’m interested in and I think that kind of time does defy commodity culture.

The critique of the autonomous artwork connects to the critique of the modernist model of resistance. But I find it questionable when ideas are foreclosed. The current answer of a radical practice is social practice, engagement with community at the level of design and social work divorced from anything resembling aesthetic concerns. I have no individual expectations that any of my paintings can have a political effect in undermining global capital or the corporatization of thought. But to eradicate the generative potential of looking at a painting, or other kind of art object, is perhaps just another victory over individual agency and subjectivity.

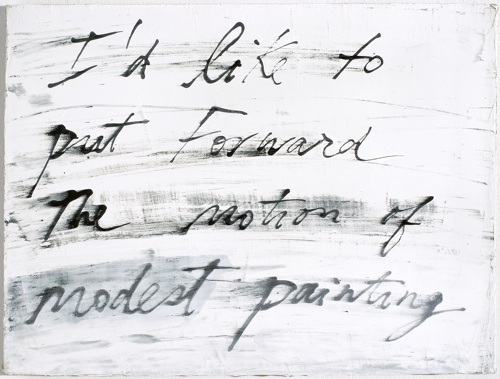

ABF: In this vein, I wanted to touch on your articulation of the idea of “modest painting” (put forth in the essay of the same name that’s in your book A Decade of Negative Thinking). This phrase does not so much refer to scale but painting where the artist focuses “on the painting itself,” not their ego, and thus skirts “the intrusion of modernist ‘styling.'” You give Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard as early examples of “modest painters” and Jack Tworkov and Myron Stout as artists who share this trait working during the time of Abstract Expressionism. Do you think this painting distinction is relevant to conversations in contemporary art?

MS: I propose “modest painting” as a counterbalance to the pressure on artists to self-commodify in order to survive with the realm of the spectacle. There are lots of paintings that are aimed for the boardroom or the boardroom-sized living room of some hedge fund manager, that are meant to compete with and support other spectacular pursuits in the culture, but there are still paintings that do something else, that work with what painting can do. I’m careful to note that not all modest paintings are small and not all small paintings are modest.

What matters to me is a kind of rigor towards painting itself, whether it be medium or subject matter. It’s not that an artist like Tworkov did not have an ego, or desires for career and name, and yet he was driven by larger ideas about meaning and methods of achieving meaning. Recently I spoke about the concept of modest painting and found myself including a filmmaker like Stanley Kubrick as an example of that quality of modesty: if you channel surf and land in a Kubrick movie you can’t stop watching it. Why? Because he has subsumed his own ego to form, he is working with narrative of course, but also framing, lighting, sound, timing, all the characteristics of film. It’s not just about him.

For myself one way I would define how that rigor enters my work is submitting my work to a constant interrogation from antithetical discourses. I’ve probably immersed myself more in the critique of painting than most painters. I stay on the train almost to the last stop, then I do get off and continue painting, but I think that trying to understand the—ever-shifting yet interrelated—terms of the critique hones my decision to keep doing it. I do have an entire other practice, of writing, and, in some cases on my blog, of the format of a photo essay, yet each means of address has its own purpose, and means something necessary for me and not interchangeable. Painting at its best gives me necessary food that I can’t get anyplace else, whether I’m the viewer or the maker.

___________

To read more from Schor, visit A Year of Positive Thinking, an online “postscript” to her printed book A Decade of Negative Thinking: Essays on Art, Politics, and Daily Life (2010).

Amanda Beroza Friedman is blogger-in-residence through March 28, 2013.