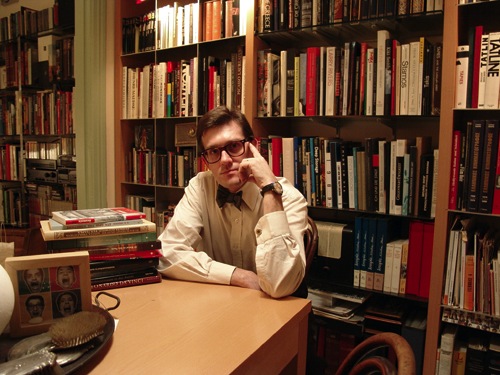

George Georgakopoulos is an art hub creator based in Athens, Greece. He attended the Deutsche Schule Athen (1976-1982), studied at the School of Fine Arts HBK Braunschweig (1983-1989), and did his postgraduate studies Meisterschueler at the HBK Germany (1989-1990). In 1991, he completed his postgraduate studies at Magister Artium. Georgakopoulos has since built an impressive resume that includes co-curating the traveling exhibition Weihnachtsausstellung at Zentrale Kunst Gallery in Hamburg (1991-1994); and co-founding three cultural organizations in Athens: Cheapart (after which he named the board game he created in 1999), The Art Foundation, and Contemporary Art Meeting Point (aka CAMP). His book Savoir Vivre for Artists was published in 2010. I am very happy to present my interview with Georgakopoulos.

Georgia Kotretsos: You started out as an artist but artist-run initiatives, curatorial projects, and collaborations won you over. What was that first project that sealed the deal for you and paved your career path?

George Georgakopoulos: My practice and research consists of two parts. The first one is the complete approach and dedication to artistic values—to the way they are formed and change daily—whereas the second is a deeper understanding of the function of art in relation to its recipient—the public.

This is undoubtedly the most difficult way to work, taking into account that in such a case the artist is expected to ignore his obvious “ego” and become a creator and recipient at the same time. Once this process is completed a new, vast field opens before us—deprived of competition and any art related anxiety. At that point only inspiration, harmonious coexistence, cooperation, and creation itself are considered of value.

As far as the first part is concerned, studying in early ’80s in Germany, I was influenced by New German Expressionism, focusing my research on purely painting values. With the passage of time and the evolution of the media, a new world was revealed in which what we think and plan is not a path trodden by imaginary people and ghosts. Reality is all around us. Daily issues set our minds into thinking processes. Each project is a comment, each project reflects our mood, and inspiration reflects our mood. Newspaper clippings, slides, expressions of speech, or behaviour constitute a source of inspiration and meditation. I do not hide what I intend to say and illustrate.

The second part is about operations and systems in the arts field, founded on the fact that artists are actually hungry for social interaction, recognition, and success. The case of Cheapart constitutes an undoubtedly successful project whose form and aesthetics I could finally plan in a free and indulgent manner. The ability to employ ideas and practices that did not exist before created a kind of school, and the project was rewarded by the acceptance of the public who can be trained in aesthetic matters. This 18-year-old course of time has changed some of the established aesthetic values and provided an opportunity for a full-range design plan that includes invitations cards, special printed matters, and catalogues. It was a natural result of multiple activities and complex fermentations between 1991 and 1994. During its second phase in Greece, from 1995 to 1999, it was designed more carefully, presenting and utilizing the works of artists who had participated in its exhibitions so far. From 1999 up to now, Cheapart has created a system that encourages artists, theorists, and art lovers towards the production of unconventional projects, often of experimental nature, a system in which the artist can create and implement his ideas and be open to collaborations with other artists.

GK: It’s one thing to build an art institution of sorts and another to create an art hub. There is an established formula for the former (with many variables) yet the latter is usually tailor-made to meet the needs of a specific art community. In your case, Cheapart, The Art Foundation, and Contemporary Art Meeting Point [CAMP] come to mind. These weren’t and still aren’t just art spaces but meeting points. How have you evolved from one space to the next, and what creative gaps do you think you might have filled in Athens with each of them?

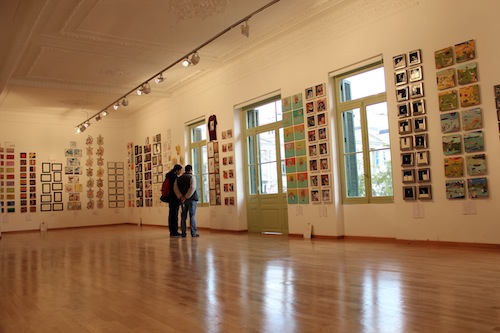

GG: Our intention is mutual understanding and collaboration between artists and curators, and as an outcome, communication with the public. The success of this goal will enable art enthusiasts to understand and approach contemporary art. As we know most serious arts organizations, museums, and institutions have a cafe or bar. In most cases, these cafes or bars are boring. It seems ours is not that way and guests often spend their time here. Since we precisely come from the world of arts, we obviously wanted the visitors of our organizations to be part of the same scene. We discreetly avoided the fleeting, mainstream crowd as we wish to establish a long-term relationship with our visitors. It’s too early to say that CAMP [founded in 2011] has been fully integrated into the arts network the way Cheapart [founded in 1995] has managed to. However, its large number of visitors shows that CAMP is loved by the art crowd and is now a reference point and meeting place for artists from all fields.

GK: You make the perfect candidate for narrating the rise and current state of the contemporary art scene (Συγχρονη Ελληνικη Σκηνη) that makes up the contemporary Greek art history of nearly 20 years. What is the art world doing now and what do you think might come afterwards?

GG: Despite adverse conditions—such as the lack of financial support and the consumerism of art spaces—active Greek artists claim that we now live in a bustling society of creators who produce work with motives and intentions, the way it happens in other European countries. However, the sense of limits in artwork in Greece castrates most artists. Ambitious ideas shrink due to the absence of financial support from official institutions, galleries, and museums. The work of art is gradually becoming a product of middleclass consumption. Artists, mainly are now self-sponsored, by continuing to create art and pursue collaborations. Nevertheless, due to these conditions, they have not learned to be consistent with their work and their gallery representation—provided the latter function properly. In any case, it is a promising situation, which should not simply remain promising, of course, with the contribution of all involved participants. Low prices on works and artist overabundance may occasionally bring frustration, but let’s not forget that artists do not survive on artwork sales but on other sources.

During recession times, like the ones we are going through today, it is rational to reduce expenses that would have been classified as a luxury, so it makes sense why art has been afflicted. Of course, since the art market in Greece has been considered a sideliner and an actual source of revenue it does not appear to have been affected by the recession. The lack of professionalism did not go unnoticed by any of the artists or buyers involved. The first ones succumb to an undignified haggling with buyers, museums, and foundations, while the second attempt to reduce already low prices even more. In these conditions, works are bought by those who believe art is not a luxury, as well as those who consider that having an artwork on display ameliorates their social status, and that the best work is the most expensive one regardless of origin or actual value. We prefer to buy cheap in an expensive manner—the trade has actually responded to this perverted demand. Value for money has been eroded over the years by multiple serigraphs or decorative sculptures of overestimated or negligible value that are mass-produced in huge numbers and sold at high prices, mismatching their quality.

We should not forget that the actual economic founders of Modern Greek art constitute an almost negligible number—and it is time to call a spade a spade. Most Greek galleries, without excluding our own, barely cover their operating costs and art promotion. Sales and distribution function as a showcase for parallel activities like product promotion, consultancy, etc. or simply manage without any financial scope in case their expenses are covered by other personal sources of income. So simply a good intention is not enough, as it is the result that counts, and the result in Greece is poor.

GK: Crisis? Are we talking about a crisis on an individual, collective, or institutional level? What’s really gone in the arts?

GG: Can crisis create art? The current economic situation in Greece confirms something that the art scene has already known and been experiencing for years: a small portion of government subsidies was spent in arts and almost nothing in visual arts. With the advent of crisis, this funding was either reduced to a minimum or completely abolished. Subsequently, the arts field was not directly dependent on the state and other ways of funding or production had to be found. We must not forget that the artist is committed to his art and that he reflects his era. It is known that artists addicted to state funding in a peculiar, doctrinal civil service manner were doomed to disappear. Time and story progresses. Artists and arts organizations are resourceful and self-reliant—they create linkages and collaborations. As a result, when crisis arrives there is a way to show that, within the general uncertainty and recession, there are areas presenting unprecedented creativity and development.

Due to these conditions, artists and arts organizations excluded impossible (or grand) programs with minimal impact usually, which could only be realized with generous state funding. As an immediate consequence, artists and art groups became independent and are once again at the heart of creation. The last two and a half to three years, a number of new art groups, organizations, and galleries boomed in Greece. This has not gone unnoticed by the international art scene, leading to increased partnerships with organizations and artists from abroad. Comprehending this new reality, we organized in CAMP a platform entitled Systems, during which we invited all independent groups and arts organizations. The first conclusion was that the vast majority of them are not older than three years. The second conclusion was that every participant has formed his own economic model in order to survive and plan for the future. And thirdly, agencies in collaboration with artists appear highly-motivated, as if awakened from slumber.

Art production has always been directly related to the social circumstances of its era. Now that social change is more relevant than ever, it is more reasonable that more artists are involved. I think the change that takes place has nothing to do with the theme, but the very structure of the artistic production and its communication with the public. What we are living is an artistic spring. In the future we will see if it led to something more international or if it was simply an inside story that will be lost.

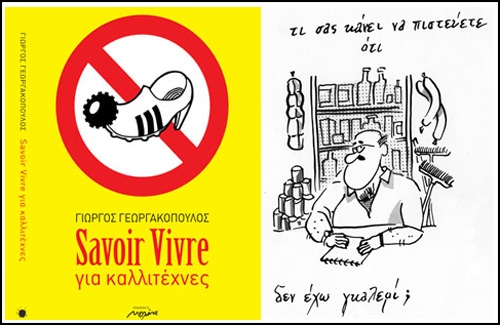

GK: Savoir Vivre for Artists—specifically for Greek artists—is an etiquette book that covers a broad spectrum of art world interactions and social scenarios, ranging from bodily propriety, decorum, and code of artistic civility to forms of dress, address, and demeanour. What made you write this intellectually hilarious book?

GG: The book presents and penetrates into the artists’ world in a clear manner without any of the hypocrisy and the false myths that surround it. Its intention is not to replace existing books, but to supplement them. Various behaviours are analyzed and annotated in a humorous and often caustic manner. Twenty years of experience as a visual artist—fifteen of which I was also in charge of two galleries—gave me the privilege of an exquisite observation of the arts field and an indepth study of behaviors.

George Georgakopoulos, “Savoir Vivre for Artists,” Melani Publications, 2010. Cartoon caption: “What makes you believe I do not own a gallery?”