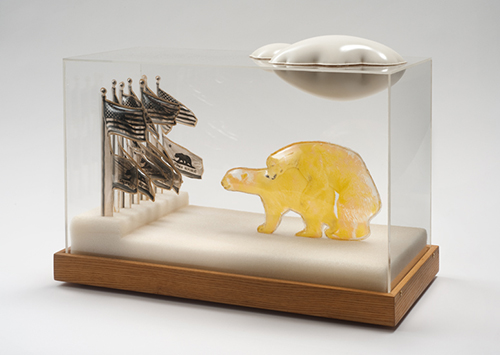

Carl Cheng, “U.N. of C.,” 1967. Film, molded plastic, Styrofoam and Plexiglas. 15 x 20.75 x 9 in. Courtesy Cherry and Martin.

In the fall of 2011, the Los Angeles gallery Cherry and Martin offered its visitors the chance to relive a once-in-a-lifetime experience. As part of Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980, gallerists Philip Martin and Mary Leigh Cherry presented selected works from curator Peter Bunnell’s 1970 exhibition, Photography into Sculpture, including some of the first examples of artists working with photographs in a “fully dimensional” manner.

The original exhibition, which debuted at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, with a roster of primarily West Coast- and L.A.-based artists, shocked and appalled its audience, winning scorn from many critics. Hilton Kramer, for instance, insisted that the integrity of the photographic process had been compromised. Forty years later, however, most of the show’s reviewers comment instead on the exhibition’s continued relevance and surprising freshness. Carl Cheng’s dioramas of molded plastic photographic figures and Michael de Courcy’s tower of photo boxes seemed as intriguing in 2011 as they did in 1970. What critics seem to disagree on was what word to use to describe the show. Was it a “re-staging,” a “revision,” or simply a “reprise?”

In an interview, gallerist Philip Martin made it clear that the goal was never to simply reach back into the past and recreate the minutiae of the original exhibition. “You want the work to live and to be present as current objects,” Martin stated. “It doesn’t feel like historical material to me.” At the same time, the effect of Cherry and Martin’s decisions to pull the exhibition forward—to apply the lens of hindsight—can’t be ignored. “Art history is a narrative. It’s a story that we’re clearly always retelling ourselves. As a gallerist, as a curator, you’re trying to create a narrative that sparks people’s interest so they can see things afresh.”

When asked if the recent version of Photography into Sculpture revised history, Martin replied, “I’m not really sure what that means. I would assume that means you’re saying to people that history is not what they thought it was. I suppose to some degree that’s true, but at the same time, I think that to reach back and say ‘Hey, we couldn’t read this object, or we were reading it in a different way…’ That’s a statement of the present.”

There’s a famous photograph from 1913 called The Smoker. The smoker sits in profile, his face double-exposed with his hairline lost against the black background. His left hand is raised toward the camera, grasping an indistinguishable object. His right hand—actually, both hands—seem to be in multiple places at once, leaving blurry motion trails across the photograph, an effect the photographer, Italian Futurist Anton Bragaglia (1890–1960), carefully cultivated by leaving the shutter open for long periods. The same technique transforms the sitter’s cigarette and cigarette smoke into solid, white cords that snake from lap to mouth.

Michael de Courcy. “untitled,” 1970-2011. Photoserigraph and corrugated cardboard boxes. 12 x 12 x 12 in each box; overall dimensions variable. Courtesy Cherry and Martin.

The image is an example of what Bragaglia called photodynamism, a process developed by Anton and his brother, Arturo, in reaction to the chronophotography of Etienne-Jules Marey. Chronophotography, according to Bragaglia, only interested itself in “the precise reconstruction of movement,” while photodynamism’s concern was with “the area of movement which produces sensation, the memory of which still palpitates in our awareness.”

It occurs to me again that there are competing versions of hindsight. One presumes distance from what came before, along with a more precise, Marey-esque catalogue of movement (of causes and effects). The second—the sight on a gun as it links my eye and my target—involves the messiness of Benjamin’s flash and the conflated instant, of multiple layers of time pierced by the same arrow. In this version, the second we loose our arrow, we enter Bragaglia’s landscape, where the legibility of individual objects and trajectories is compromised and nothing is as important as the connective tissue that vibrates between and around things.

There is no prescription for the results of such an encounter, but perhaps this is a way we can have our cake and eat it too—to steal fire and bring our past along. After all, the clumsiest narratives are often the narratives that assume prescribed movement from A to B. Perhaps what makes shows like Cherry and Martin’s stand above the rest is that they don’t.