The facade is clean and white, and the shutters are a quaint blue. But step across the threshold and any conventional notions of a house are checked at the door. Above ground, an interior with select furnishings features clean white walls and a dedication to flux as a community-oriented space. Descending into the basement, a two-level subterranean space designed for “private rites of an aesthetic nature” unfolds. Rooms intended as working spaces for artists are connected by a series of corridors and ladders; there are no windows or doors. Welcome to Mobile Homestead, conceptual artist Mike Kelley‘s new permanent installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit.

The opening this month at MOCAD follows a recent retrospective of Kelley’s work at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Originally conceived as a mid-career survey, the artist’s death in early 2012 prompted the expansion of the exhibition at the newly reopened Stedelijk into a comprehensive survey encompassing over two hundred works from a prolific career spanning more than three decades. Reflecting upon the history of his work in tandem with the recent opening and vexing design of Mobile Homestead, I consider the memory of Mike Kelley—both literally and figuratively.

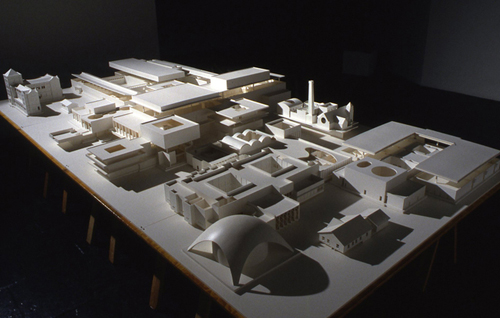

Memories provide the very fabric of our beings as individuals, creating an intricate and unique web woven from lived experience. Kelley long mined such personal terrain to explore the deep and confounding layers of the hidden, unconscious or forgotten. In the process, he revealed where the threads of remembrance and forgetting intertwine. For his 1995 work Educational Complex, the artist created a large-scale model including every school he’d attended as well as his childhood home. By intentionally leaving parts he could not remember blank, he aimed to illustrate “architecture as it relates to memory—how unfixed our memories of space are.” In so doing, he also created a tactile map of nebulous space, a visual representation of the places where such links begin to unravel.

When asked by Glenn O’Brien to discuss the conceptual ideas behind Educational Complex in a 2008 interview, Kelley stated that he “wasn’t really interested in remembering anything” specific to their physical structures. In creating a model of the formative spaces of his youth, it was actually the blanks he sought in order to fill them in with his personal fantasies—a blending of fact and fiction. “I found that I was filling in the blanks with pastiches of a lot of things that had affected me when I was a child—like cartoons or films or stories I’d read or things I’d heard.” By embracing these gaps as generative conceptual ground, he considered absence as form and the catalyst for distillation in navigating layers of the past.

I’ve been following Mobile Homestead since 2010, when I was a graduate student at Cranbrook and when the project was literally set in motion. A life-size replica of Mike Kelley’s childhood home made a roving journey from Midtown Detroit back to its original site in the Detroit suburbs, resulting in a series of videos featured in the 2012 Whitney Biennial. Since then, the replica has been integrated into the development of a permanent site adjacent to MOCAD, the most fascinating aspect of which is the labyrinth built underground. The subterranean levels are meant to echo the floor plan of his original family home, but structured in such a way that, as Kelley explained, “its floor plan is unrecognizable as the mirror of the house above.”

Mike Kelley, from the “Kandor” series, 2011. Mixed media installation. Opening night at Gagosian, Los Angeles, January 2011. Photo: Erin Sweeny.

Last year, O’Brien published an expanded version of his studio conversation with the artist. There, Kelley again referenced the idea of the mirror: “We’re surrounded by invisibility, and that’s what I think art is about…it is about making things visible. You’re a mirror of the world—maybe a warped mirror.” Mobile Homestead is the artist’s first public art project anywhere and the first major permanent installation of his work in his hometown. Carrying the conceptual threads of earlier works into this life-size recreation, he leaves us with the opportunity to enter his own memory, experiencing the space as he remembered it, and the uncanny reflection of the space he sought to fill. In Kelley’s universe, it seems a fitting tribute.