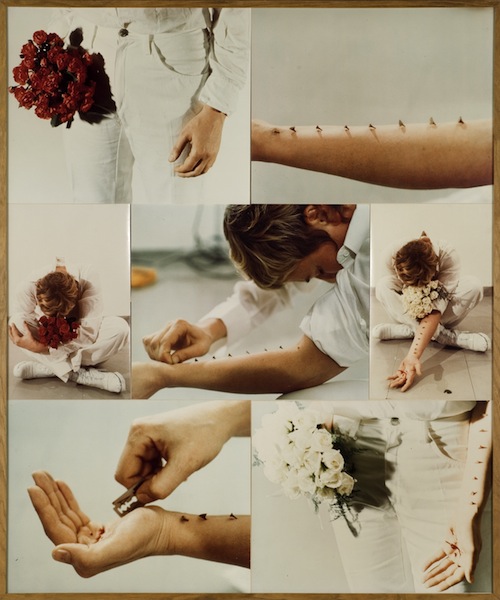

Gina Pane. “Constat d’action for Azione Sentimentale (Sentimental Action),” 1973. 7 color photographs mounted on wood panel. 48 x 40 in. Photo: Françoise Masson. Courtesy kamel mennour, Paris.

June marks the closing of Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art and Ana Mendieta: Late Works 1981-85 at Galerie Lelong, both in New York, and Parallel Practices: Joan Jonas and Gina Pane at the Contemporary Art Museum in Houston. It just so happens that all of these exhibitions pay tribute to women who found most of their fame posthumously, with the exception of Jonas whose career continues to flourish. Their careers span Beat poetry, Happenings, and body art, genres that while linked to multiple cities (San Francisco, New York, and Paris) speak to a unique era of radical consciousness.

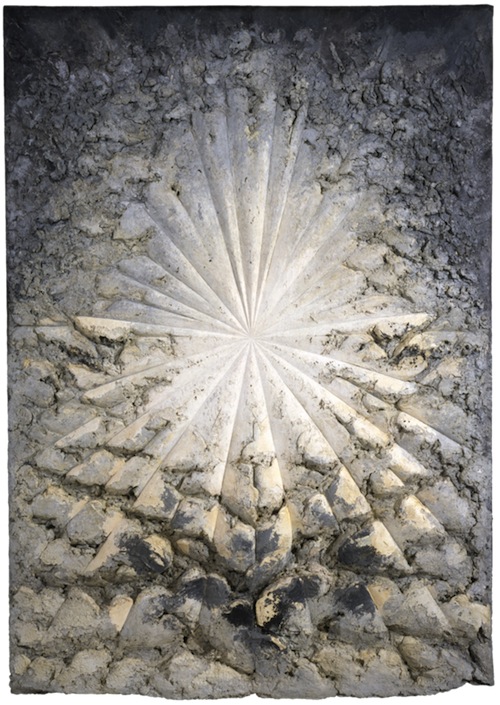

Jay Defeo. “The Rose,” 1958–66. Oil with wood and mica on canvas, 128 7/8 x 92 1/4 x 11 in. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of The Jay DeFeo Trust, Berkeley, CA, and purchase with funds from the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee and the Judith Rothschild Foundation 95.170. © 2012 The Jay DeFeo Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Ben Blackwell.

Painting was a way of life for Defeo. Take, for instance, her nearly 2,000-pound gesamtkunstwerk The Rose (1958–66). Objects that were part of DeFeo’s daily life fell into the painting, becoming part of its layers. Filmmaker Bruce Conner documented its dramatic removal from the artist’s apartment, where a wall had to be cut just to pack it. Struggling with letting the painting go, Defeo laid down on top of it before it was carried away by forklift. The Rose is as much an event and performance as it is an object. At the Whitney, lit from the sides, as it would have been in the artist’s apartment, The Rose radiates as if it is alive. It is impossible to look at it without sensing the labor involved and experiencing something of DeFeo herself; the painting is corporeal. Crescent Bridge I and Crescent Bridge II, paintings of her dental bridge magnified to great proportions, also convey this corporeality and sense of light. Images from DeFeo’s studio show one of these paintings in progress alongside Xeroxed reproductions of the moon.

French-born artist Gina Pane was a founder of body art or “art corporel” in the 1970s and was known to use self-inflicted wounds as an aesthetic device. This she combined with sculpture to create montages known as “constat d’action” (proof of actions). One example, Azione Sentimentale (1973), is on view in Parallel Practices: Joan Jonas & Gina Pane at the Contemporary Art Museum in Houston. Curated by Dean Daderko, this marks the first comprehensive U.S. exhibition of Pane’s work. “People think of Pane as the artist who cut herself, but there is a much larger context for her work in the world,” said Daderko. “Pane made a conscious decision to avoid spectacle, but she was interested in looking at suffering and religious iconography. She drew from the formal qualities of Quattrocento painting to make her constant d’action because she wanted to create a formal framework for her literal wounding.”

Daderko invited Joan Jonas to participate because, as the exhibition title suggests, her body-based work emerged concurrently. Like Pane, Jonas studied painting and drawing but would later include video, musical scores, and performance. At the CAMH, her early video work and drawings are on view, as well as her recent installation, Reading Dante III, which includes a 4-channel video, wall drawings, and sculpture. Each Saturday, CAMH will host a restaging of Jonas’s 1970 performance, Mirror Check. “Jonas was interested in using her body as a reflexive tool in performance and video,” Daderko commented, “and in working with it as material, which came out of her experience in the Happenings scene.” Comparing Jonas to Pane, he said that Pane ”was seeking a frame for her performances” where “Jonas was seeking to break the frame, and create a world where no one element is privileged over any other.”

Further describing his curatorial vision for Parallel Practices, Daderko explained: “I am interested in the space of questioning as a point of entry for the viewer. The work in Parallel Practices is meant to provoke dialogue as a generative space of questioning. I wasn’t interested in proving a point by creating a hermetic seal of meaning for the viewer. I think of the work of these artists as a ‘continuous present,’ where the objects have the potential to continually activate new perceptions.”

Ana Mendieta. “Birth,” 1981. Super-8 black and white, silent film transferred to DVD/ TRT: 2:03. Edition of 6. © Estate of Ana Mendieta, Courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York.

Daderko’s idea of a continuous present is also apparent at Galerie Lelong in Ana Mendieta: Late Works 1981-1985. Video documentation of the artist’s signature landscape series, Siluetas, show these imprints of her body as they are transformed by fire, wind, and the ocean tide. The transformation of each Silueta is subtle at first, as waves lap at the figures or smoke slowly wafts through the air, but the elements eventually overtake them. The performative aspect of these works is mostly private: viewers see only traces of Mendieta’s body, never her efforts to dig up the earth or place her body down in it. We do, however, see her lay down once for Birth (1981), though she may only have been checking to make sure the camera angle was correct. Siluetas serve as a ghostly reminder of the artist’s presence and a presaging of her untimely death.

What all of these exhibitions reveal is a shared curatorial desire to retrace the legacy of multidisciplinary practices. It is no coincidence that DeFeo, Pane, Jonas, and Mendieta have had major shows at the same time. As artists emerging from a modernist, male-centered art world, these women redefined studio art, incorporating new media, their bodies and their lives.