Jason Lazarus, “Michael Jackson Memorial Procession,” documentation by MJMP participant, 2010. Courtesy the artist.

Elvis made regular appearances in the periphery of my youth by way of Reno casinos, Las Vegas performances, and supermarket tabloids. The proliferation of professional Elvis impersonators, alongside a constant assortment of sightings and speculations that his death was a hoax, led me to understand the pop star’s influence before knowing anything about his music. Culturally, it would seem the country was not ready to let go of their musical icon; feigning and practiced denial of his death became a collective, immaterial game at remembrance. The same could not be said of Michael Jackson. While arguably surpassing Elvis’s field of influence, Jackson’s end was never a question. Immediately following his death Chicago’s regular soundscape transformed into an ad hoc and unchoreographed musical tribute, or what Chicago-based artist Jason Lazarus calls “a constantly changing” and “fascinating urban sonic memorial.” Lazarus attended to the sound of Jackson’s aftermath. “MJ blasted from cars, shops, house, and apartment windows. It was MJ’s massive following across age, race, sex, ethnicity that allowed [this] to occur.”

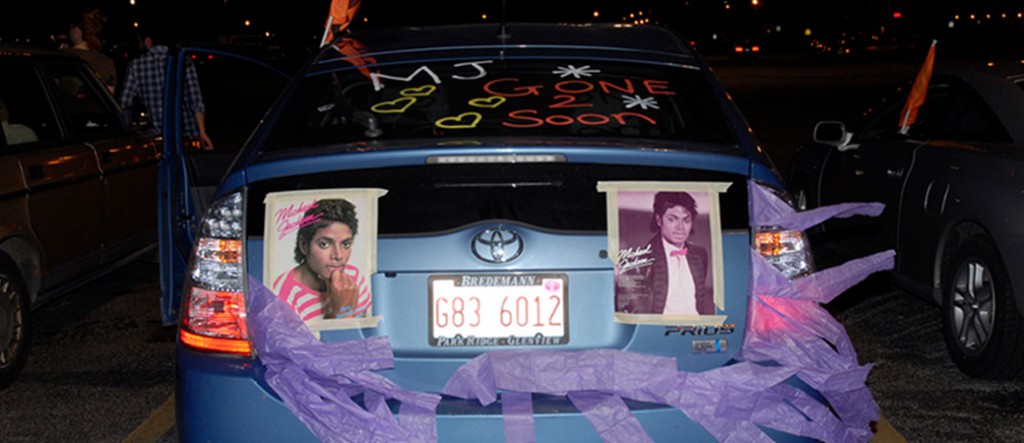

Jason Lazarus, “Michael Jackson Memorial Procession,” documentation by MJMP participant, 2010. Courtesy the artist.

One year later, Lazarus reenacted the pop star’s unofficial funereal soundscape in Michael Jackson Memorial Procession (2010). For this work, he organized a multi-car procession where artists, friends, and fans met at Jackson’s boyhood home in Gary, Indiana. The city had already organized a street fair. “There was a festival with a stage featuring MJ impersonators, a choir, various speakers, extended family, all surrounded by DIY MJ merchandise hustlers, BBQ, decorated fans, and tourists. We met in the parking lot; the mood was exciting.” After Lazarus gave a speech through a megaphone, about one hundred attendees climbed into some thirty cars and drove en masse to Chicago. Over the course of the procession, Lazarus broadcast a pirate radio station that traveled with the caravan, linking each discrete car with the same Jackson playlist. The cars were decorated like vehicles going to a sports rally, except in this case decorative window paint read “Gone 2 Soon,” “Listen for MJ on 87.9 FM,” “Thriller Mobile,” and “R.I.P Michael.” In some instances, paper printed portraits of Jackson from various stages of his life were fixed to car exteriors. All participants were given disposable cameras to document their experience.

“Getting on the highway [in Gary] was particularly wonderful,” says Lazarus. “Our MJ funeral flags were waving and it was early sunset. We started to get our first looks, honks, and screams of approval. There was such high energy! We ended after five to six hours at the Aldi parking lot on Milwaukee Ave [in Chicago], just north of North Ave. We danced in the parking lot, blasted more music, and lit sparklers. Everyone was exhausted and exhilarated at the same time.” The resulting interactive event—part performance, part reenactment, part reflection—mirrors Jackson’s peculiar and profound relationship to the public, while highlighting the physical and ideological infrastructure that supported him.

Jason Lazarus, “Michael Jackson Memorial Procession,” documentation by MJMP participant, (Gary, IN), 2010. Courtesy the artist.

Part of what is so interesting about Michael Jackson is the way he embodies an era, reflecting an industrial shift while epitomizing the furthest extent of the American Dream. Gary, Indiana is a perfect example of an old industrial town that suffered when production shifted overseas. Meanwhile Jackson’s ability to disseminate and promote his work was part and parcel of that same pitch towards globalization. Signs of Jackson became as ubiquitous as McDonald’s and Coca-Cola logos—signs that, to the general public, were more palpable than the physical, personal body of the artist. It seems fitting, therefore, that Lazarus’s procession never tried to embody the pop star. Instead Lazarus conjured Jackson’s aura using a constellation of vehicles that activated his memory, to such an extent that a surrounding (and shifting) public was compelled to participate as well. “We wanted to hit a number of different audiences, geographies, and socio-zones,” he says. “We got responses from everyone!” Michael Jackson Memorial Procession illustrates the complex network surrounding Jackson’s stardom, incorporating the American road as a memorial site, celebrating the poster boy for a bygone era, and the tragedy implicit in Jackson’s personal life.

Elvis represents a normative, rock and roll machismo. Embodying his persona is less complicated than embodying Jackson’s. In fact, the more ubiquitous Jackson’s image, music, and reputation became, the more slippery his gender, race, and sexuality.

Zero Books put out another kind of memorial in 2009 when they published a collection of essays, The Resistible Demise of Michael Jackson. The collection focuses on the arc of Jackson’s personal life and career in a mix of critical and biographical inquiry. It does not shy away from the uncomfortable aspects of the star’s persona and, perhaps for that reason, Jackson’s physical body is always at the fore, beside the memory of his music. As Steven Shaviro points out, “Jackson’s self-remaking can only be understood as a kind of Afrofuturist nightmare; a violent (to himself) leap into the posthuman.”1 Jackson’s corporeal shifts reinforced a constant sense of disembodiment, as the pop star fashioned himself into an ongoing, unstable assemblage of parts. Just as Lazarus deemphasizes the single, physical body, the structure of the Michael Jackson Memorial Procession is not about a single perspective, or a single approach to linear story telling, instead it contains an assemblage of individuals—even the responsibility of documentation was shared.

Jason Lazarus, “Michael Jackson Memorial Procession,” documentation by MJMP participant (South Halsted St. in Chicago), 2010. Courtesy the artist.

There have been other works of art that tribute Jackson: Jeff Koons’s Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988), of course. Paul McCarthy’s sculptural reenactment of Koons’s sculpture, Michael Jackson Fucked Up (Big Head) (2002). And the especially saccharine and disconcerting paintings by David Nordhal from Jackson’s personal art collection. Most examples function as portraits: static images with central depictions of the music legend. Perhaps as a result of this portrayed embodiment, these works tend to inspire a queasy sensation. Mark Flood gave Jackson many faces and set him beside ET, suggesting the two figures are friends in alienation. Which is perhaps what made Jackson’s death so strange in the end—at that point in his career his influence on the world seemed to exist without his body.

“What haunted me in the first day or so after Jackson’s death…as I watched all the videotapes on constant rerun on the music channels…as I listened to the chat of people in cafes, all of us going through the by now well-rehearsed routine of mass-mediated death…what haunted me was the difference between how Jackson looked in the Off the Wall videos and how he appeared in the Thriller clips.”2

Jackson’s body was always a sticky situation, one that some artists seem to insist upon. Candice Breitz reflected an alternative (and perhaps more accurate) depiction in King (A Portrait of Michael Jackson) (2005/2006). Breitz put out a call for fans to sing the entire Thriller album in one go. She selected sixteen participants based on earnestness. In the resulting video, she projects each figure on the same screen singing his or her own musical rendition side by side. Like Breitz, Lazarus focused less on Jackson explicitly and more on the experience Jackson inspired—an experience that was collective rather than singular.

Jason Lazarus, “Michael Jackson Memorial Procession: Michael Jackson’s boyhood home,” 2010. Courtesy the artist.

It may seem strange to look back at Jackson’s passing after all of this time. But his astounding mash up of artistic genius, commodification, success, persona, perversity, and influence are prescient. The mystique of celebrity seems only more mesmerizing now, particularly as homages to its deconstruction proliferate. James Franco is an obvious example, as is the Abromovic/Lady Gaga team, but consider too Tilda Swinton’s recent appearance in her glass vitrine at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Or the David Bowie retrospective; set to arrive at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago this September, the exhibit promises to show 300 objects from Bowie’s “personal 75,000 piece archive,” not works of art per se, but ephemera from his musical career and creative processes. It will no doubt be a blockbuster. Like Swinton’s epic nap, its position in a contemporary art museum affords a duplicitous irony, at once earnest in its reverence and critical by way of obsequious excess. These celebrity appearances seem rebellious at first—as the farthest extension of Warhol’s soup cans. The human persona is the art. And while those personas have profound effects—to such an extent that, as Lazarus demonstrates, they can inspire community—they nevertheless occupy and propagate another exclusive world of capital’s demigods.

An iteration of Lazarus’s Michael Jackson Memorial Procession is currently on view in Love to Love You, a group show at MASSMoCA with a collection of works that pay homage to celebrities.

NOTES

1 Steven Shaviro, “Pop Utopia: The Promise and Disappointment of Michael Jackson,” in The Resistible Demise of Michael Jackson, ed. Mark Fischer. (Winchester: Zero Books, 2009), 61.

2 Mark Fischer, “And When the Groove is Dead and Gone: The End of Jacksonism,” in The Resistible Demise of Michael Jackson. (Winchester: Zero Books, 2009), 9.