Responses to recent developments over at the National Security Agency (NSA), and growing concerns about privacy in general, point to our desire for a certain amount of control over our online activities. Crowdsourced artworks give users some authority, if even just a little, and the creators are usually transparent about how user participation gets tracked. Sometimes, that’s part of the fun. Following are some thoughts and observations on two recent crowdsourced sound works that provoke questions about virtual engagement.

Do Not Touch

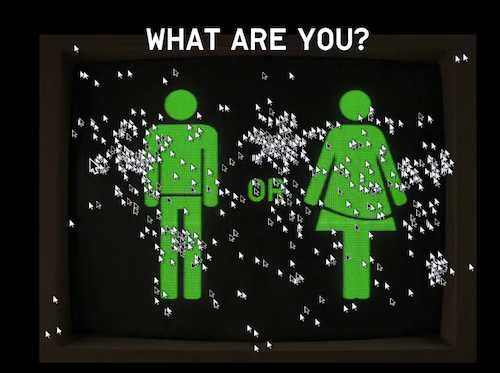

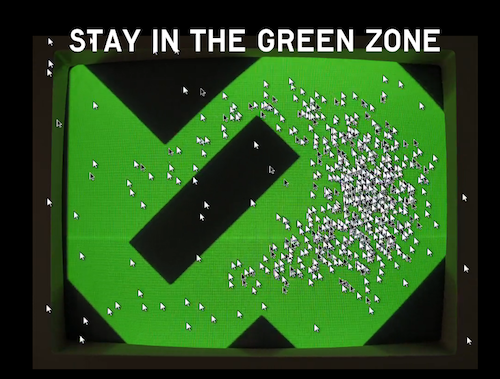

Moniker for Light Light, “Do Not Touch” screenshot, 2013. Crowdsourced music video.

Created by the Amsterdam-based design and technology firm Moniker, the crowdsourced music video Do Not Touch (2013) was made to accompany “Kilo,” a song by the European band Light Light. “After 50 years of pointing and clicking,” says the website, “we are celebrating the nearing end of the computer cursor with an ever-changing music video where all our cursors can be seen together for one last time.” Upon clicking the play button, the viewer is presented with a frenetically moving mass of arrow cursors, representing the users who participated in the video’s creation. Text at the top of the screen shows the instructions they received on how to move their cursors, reading for instance, “Catch the Dot” or “Stay in the Green Zone.” When presented with a map, users were given questions like “Where are you from?” and “Where would you like to go?”

Moniker for Light Light, “Do Not Touch” screenshot, 2013. Crowdsourced music video.

The language prompts, which play a huge role in how users interact throughout, are, maybe problematically, only offered in English. The lyrics “fight against the current” suggest that the listener and user too are subjects in a controlled environment. At work here is Moniker’s larger objective to explore our relationship with technology. Do Not Touch serves to comment on how we engage with other users online, and also tells us something about our different ways of following instructions or not. My favorite part of the video instructs the viewer not to touch the nude model. However, a few users were compelled to cover her private parts, or at least point to them. Do Not Touch gives us a glimpse at how people move with or against a crowd. But how much control does the user really have?

Seaquence

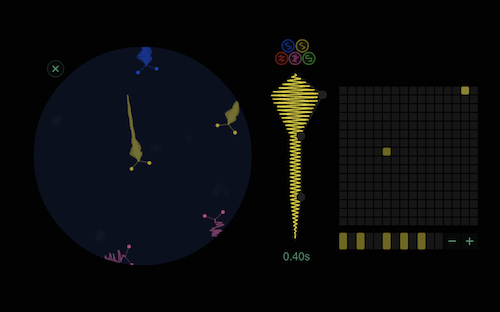

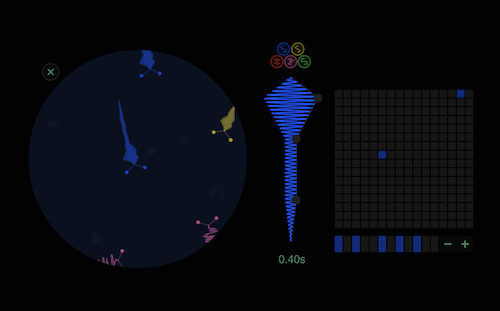

Ryan Alexander, Gabriel Dunne, and Daniel Massey, “Seaquence” screenshot, 2013. Crowdsourced soundscape.

Seaquence (2013), “an experiment in musical composition,” also invites users to become co-producers. Designed by artists Ryan Alexander, Gabriel Dunne, and Daniel Massey at Gray Area Labs (part of Gray Area Foundation for the Arts in the California Bay Area), the trio created a virtual environment where users “can create and combine musical lifeforms” in a Petri dish. The user has the ability to build an entire ecosystem from the sound waves, which resemble tadpoles. Although Seaquence is based on a specific script, resulting in a variety of tones and sounds, it is ultimately the participant who creates a unique musical composition.

Ryan Alexander, Gabriel Dunne, and Daniel Massey, “Seaquence” screenshot, 2013. Crowdsourced soundscape.

What drew me to Do Not Touch and Sequence is the focus on the user as the producer of content—people are actually needed to create the work. In my recent research and writing, I’ve focused on “digital colonialism,” or technology as a form of control as we increasingly rely on digital devices. Do Not Touch and Sequence emphasize the artists and designers role in perhaps decolonizing the user by inviting him or her to take action. But the projects bring me to question the limits of engagement with audiovisual artworks online. Are they really liberating? Or are they restrictive? How have these works encouraged you to think about our relationship with technology, and the viewer as content creator?

Dorothy Santos is Art21’s blogger-in-residence through August 30, 2013.