Ernesto Pujol, Farmers Dream, 2010. Performance rehearsal at the Warehouse in Salina, Kansas. Courtesy the artist.

I first crossed paths with Ernesto Pujol when I was a graduate student at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. He was a visiting artist in the sculpture department, where I was attending a Dia de los Muertos–themed dinner hosted in his honor. Themes and costumes made from hastily gathered studio materials were always integral to such events; I recall wrapping myself with brightly colored tissue flags in an adjacent studio moments before. The Day of the Dead theme would prove fitting as I conversed with the artist, compelled by his calmness, sense of center, and innate reverence. In speaking with him more recently about the evolution of his work—and in particular his project, The Field School—I have also discovered a gentle but tenacious practitioner, one who beautifully embodies Carol Becker’s notion of the artist as public intellectual.[1]

Pujol assumes a complex set of roles with the undertaking of each project. He identifies as a site-specific, public performance artist and social choreographer, taking on the varying roles of artist, archaeologist, ethnographer, educator, public speaker, and manager. His projects reveal an intense dedication to engaging student-participants at all levels. Since 1999, Pujol has explored the notions of the visiting artist and artist-in-residence in providing field training for graduate and postgraduate art students. Further, in reaching out to the local public at varied sites and inviting them into the production process, he works to create an accurate portrait of a people and their ideals, embodied in what the artist describes as “emblematic historical architecture, which they have often stopped seeing.”[2]

Ernesto Pujol, Memorial Gestures, 2007. Performance rehearsal at Chicago Cultural Center. Courtesy the artist.

This collaborative, project-based approach has also served as the groundwork for The Field School, established in 2006 in response to students who sought more of the unique learning and working experiences facilitated by their involvement in these projects. Specifically, it was after Pujol created Memorial Gestures—a work staged at the Chicago Cultural Center with undergraduate and graduate students from the School of the Art Institute, about mourning the war in the Middle East—when its participants requested that the process continue. Describing the school as “an ephemeral classroom with legs walking around the city,” the artist has subsequently trained participants in all aspects of conceptualizing and producing durational performance as contemporary public art, fully citing their art training in society. In exploring what he terms as the “pedagogical potential of social choreography,” his teaching style aims to bridge artists and mainstream audiences.

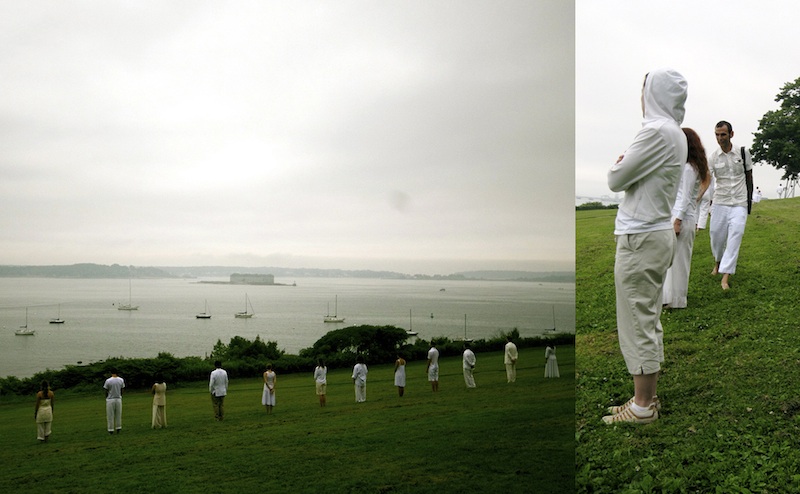

Ernesto Pujol, Visitation, 2011. Performance at the Spencer Art Museum in Lawrence, Kansas. Courtesy the artist.

This program also serves as an important tenet of Pujol’s critique of the current state of art education at the graduate level, an industry the artist-educator argues is unsustainable based on the high number of MFA programs with redundant curriculums being fueled by emerging artists amassing frightening amounts of student-loan debt.[3] While I believe he has a valid point in arguing for the downsizing of some MFA programs, I hold onto my belief that the benefits of a solid program are unquantifiable—especially programs that encourage a cross-disciplinary approach (though it is fair to say that I am biased due to my personal and financial investment in an MFA degree). For me, the more compelling part of his argument lies in his suggestions for how existing programs might adapt to the needs of a changing society and a new generation of artists. As Pujol said:

“What I propose is that the remaining MFAs take on very public points of view: that they take on their citizenships; that they function as active citizens in their cities. Some should be unapologetically artisanal, if landed craft is what their region is about; some should be about art as social practice, sending their students as interns into all sorts of non-cultural service institutions, addressing social ills; some should be new-medium-specific, providing comprehensive technical training in the cultural currency of our day, in photography, video, and performance. And all should be art-interdisciplinary, combining art training with equally deep training in other disciplines.”

Pujol currently teaches in graduate programs at Parsons/The New School for Design and the School of Visual Arts (SVA); at the latter he is part of a new low-residency program in art practice headed by David Ross. Whether working collaboratively in the field or within the framework of an evolving program at a well-established institution, Pujol’s commitment and transparency reveal a sense of trust that is inherent in all aspects of his practice. By opening and sharing his process, he facilitates an educational experience that is rooted in the collective experience and potentially generates lasting impact.

In researching The Field School (and Pujol’s work in general), I learned of his influence on others such as Nomad/9, a cross-disciplinary educational initiative that is being developed by Carol Padberg through the Hartford Art School. Padberg cites Pujol’s writings as a catalyst. After reading his essay in Art School: Propositions for the 21st Century, Padberg reached out to Pujol to discuss the development of an experimental MFA program. He would become a generous participant in her informal think tank for the program. Padberg explained:

“In 2011, three experiences coalesced for me. I took my first group of students to Ghana and realized how much better the pedagogical and creative process unfolds outside of the walls of a school. A few months later, I joined a three-week session at Mildred’s Lane. There I experienced Mark Dion’s and J. Morgan Pruett’s design of an intentional, expanded pedagogical model. During all of this, I was reading and discussing Ernesto’s writings on the education of artists.”[4]

Padberg described the effects of Pujol’s writing as a clear call for action, rooted in deep experience.

Becker’s notion of the artist as public intellectual again comes to mind, emphasizing the important role of these artist-educators in encouraging students not only to question and push boundaries but also to pause and reflect. On October 3 and 4, 2013, Pujol will present a new piece entitled Time After Us for the Crossing the Line performance festival of the French Institute in New York City. With a team of performers, the artist will walk a titanic circle for twenty-four hours inside St. Paul’s Chapel on Wall Street. The space holds a powerful sense of history for the city; it is where President Washington prayed after his inauguration, and its colonial structure has survived fire, terrorism, and flood.

Considering Pujol’s upcoming project, I pause and return to the memory of our first encounter at Cranbrook and the strong centeredness I first sensed from him. Reminiscent of a clock, Pujol’s work continues to extend and control the steady arms that move forth from its core.

_________________

[1] Carol Becker, “The Artist as Public Intellectual,” in Surpassing the Spectacle: Global Transformations and the Changing Politics of Art (Rowman and Littlefield, 2001).

[2] This and following quotes are from the author’s conversation with the artist on July 14, 2013.

[3] Two textbooks feature his insightful essays on the subject: Art School, Propositions for the 21st Century, edited by Steven Henry Madoff (MIT, 2009); and Learning Mind, Experience Into Art, edited by Mary Jane Jacob (University of California, 2010). There is also an online article that Pujol wrote in 2012 for DIS magazine, “Throwing the Gauntlet @ Art Programs,” https://dismagazine.com/discussion/32984/throwing-the-gauntlet-art-programs, accessed August 24, 2013.

[4] From the author’s conversation with Carol Padberg on August 2, 2013.

Pingback: Letter from the Editor | Art21 Magazine