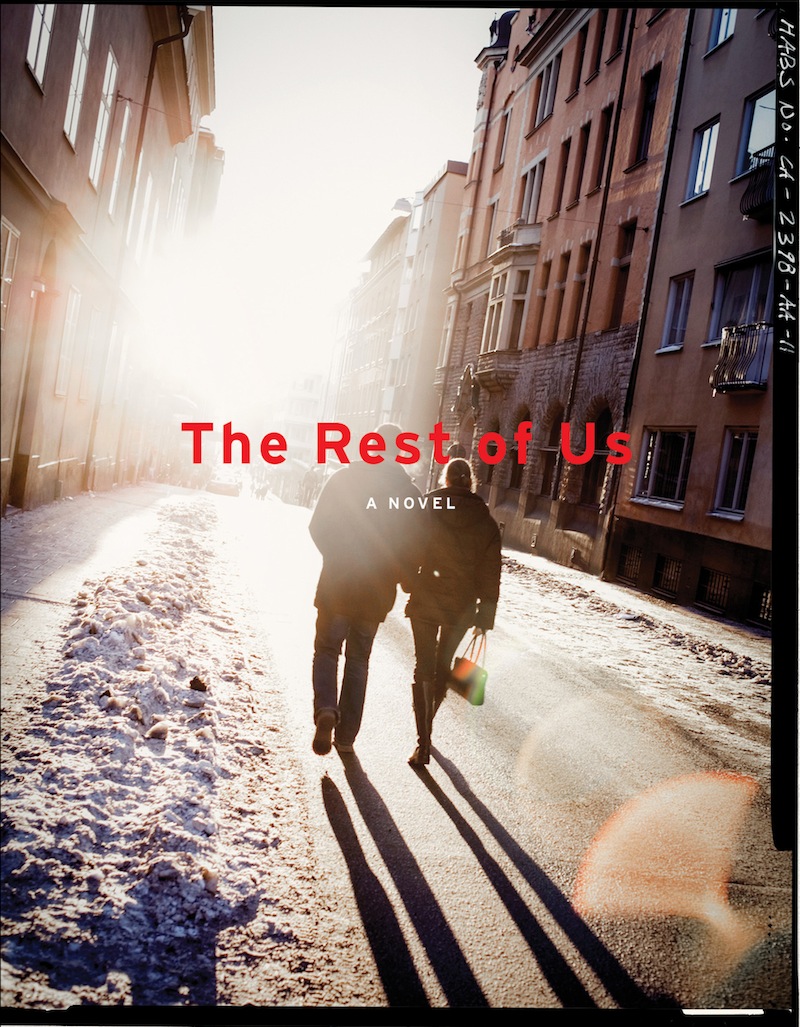

Editor’s Note: In July 2013, Art21 columnist Jessica Lott celebrated the release of her first novel, The Rest of Us, published by Simon & Schuster. Set in New York City’s art world, The Rest of Us is a love story that tells of an affair between a college student, Terry, and her older professor, Rhinehart, and its impact fifteen years later. Lott touches on our theme “Becoming an Artist,” as she brilliantly conveys, alongside the affair, the highs and lows of Terry’s career in photography. Called a “stellar fiction newcomer” on NPR “Fresh Air,” The Rest of Us has been described as “a love letter to the city and the struggles of its artists” as it is “a sharp and stirring novel of the heart.” Art21 is pleased to publish the following excerpt:

Chapter 1

It was the beginning of November. Exactly fifteen years ago, I’d been nineteen, and in my junior year of college in upstate New York. I drove a rattling Nissan and wore the same pair of maroon corduroys every day—they were split in the left knee, and in the cold, the wind would slip in and deaden the skin. I sort of liked the sensation, but Rhinehart feared frostbite, and bought me thermals I refused to wear, and a bright green beret that he styled perched on the back of my head. I pulled it down, like the droopy cap of a straw mushroom, so that it covered my ears. My ears were a source of embarrassment to me, the way the tips protruded from between the strands of hair, which was a nice brown and long but too straight. I mostly wore it up with bobby pins that dislodged and were scattered around the house, he said, “like feathers from a rare bird. They let me know where you’ve been.”

“You keep it too neat here. Otherwise you wouldn’t notice.” Except when he was writing, the only mess was stacks of newspapers and journals, the occasional used coffee cup, or jelly jars stained red in the bottom from wine—the living room of the house he rented for the duration of his time as a visiting writer at my college. This was what he had chosen—an old house with creaking doors and a bathroom under the staircase. He’d brought some of his furniture, striped low-back couches and an enormous featherbed that he’d dragged his library into, so that we often kicked books onto the floor when making love. He was working on the collection of poetry that would win him the Pulitzer, through miserable fits of self-doubt and manic intensity that made life even more exciting for me than it already was.

I’d met him at an artist lecture in town that summer, two months before he’d started his appointment at the school. We’d started talking about our mothers, both of whom had died when we were young. Slightly embarrassed, he’d revealed that he’d just attended a séance in Manhattan, and described the cramped, overheated room into which his mother didn’t appear. I reached into my pocket and showed him pebbles that my mother had collected from the beach near our house. It was bizarre and superstitious but sometimes, if I was feeling nervous, I’d carry them around, knowing she had once touched them. She had died when I was three. Unlike other people, Rhinehart didn’t assume that because I couldn’t remember her, I didn’t miss her.

Afterwards, I knew he was someone I wanted to be around. If I hadn’t been in the grip of some sort of magical thinking, I would have recognized that he was in his forties, nearing the height of his career, and a professor. I would have been intimidated, rightly. I would never have had the guts to pursue him. I told myself, I’ll just try and get to know him better. But it wasn’t as easy as all that. It took me weeks to distinguish myself from the other young people milling around town that summer. We did become friends, but by then I felt we should be together and said so. He had discovered that I was a college student and was reluctant.

I plowed ahead, too confident in the connection between us to be dissuaded, and in the end I was right. Once he’d overcome his own objections, we’d moved very quickly from dating, to falling in love, to being in a relationship. He was continually amazed by how visual I was—it made his powers of observation “crude by comparison.” When he’d said this, I’d been crouched down on his floor, studying a spiderweb spun between two storm windows, and the shadow it cast. I was a photographer, or an aspiring one. That fall, I was often at his house, shooting—the slim white birches just beyond the porch, sun on the floor, Rhinehart’s fingers gripping a pen, the blond stubble on his face. I had almost too many ideas. In the morning, I’d disappear on my bike to take pictures in the woods, returning to a large, silent afternoon indoors, steam hissing up from the radiators. We’d sit on opposite ends of the couch, Rhinehart crossing out lines in a yellow memo pad, while I sketched future projects, and the fickle sun moved back and forth in the doorway. Occasionally, when he wasn’t looking, I’d watch him. I had been excruciatingly happy. For months, I walked around with a foolish smile on my face. Everywhere, even in the bathroom.

The obituary had appeared online, and I printed it out to show Hallie. She’d been my roommate throughout college and after, when we first moved to Manhattan. I still lived in the apartment we had shared for years.

She was already waiting for me in a café on Jane Street. “What’s the big mystery?”

I took the obituary out of my purse and passed it to her.

“No way.” Both of us stared at his photo. He was in profile, looking at someone out of the frame and smiling. “When was the last time you saw him? College?”

I nodded. Rhinehart and I had been together less than a year. He took a job at Columbia University the fall I was a senior and moved to the city. After I graduated, I moved here, too, but we’d never met.

I watched her read, her lip pinched between her fingers, her floating green irises like planets. Next to hers, my face had always seemed plain— like a farm girl’s I used to think when feeling down. We’d grown up together on the North Fork of Long Island, but while my father had greenhouses, hers worked in Manhattan. She had spent overnights in the city, knew how to make us sexy ripped T-shirts, and sneak on the Orient Point ferry without paying.

She put the paper down. “How are you taking this?”

After the shock of it, I was depressed. Also incredibly disillusioned. “I was so sure we would see each other again. I can’t believe how wrong I was.” But then again, I’d been wrong about other things. My future as an artist. I’d basically stopped shooting, if you didn’t count my job at Marty’s portrait studio. I hadn’t even noticed until about a year ago. Where had all that time gone? It was as if New York had swallowed it, along with my twenties. I’d revolved through possible solutions—sketch out some ideas, take a class at the ICP, buy a new camera. Instead I agonized and then did nothing. How effortless making my own work used to be. That’s what I remembered of that time. That and what it had felt like to be lying on Rhinehart’s bed, shirtless, in my corduroys, giggling.