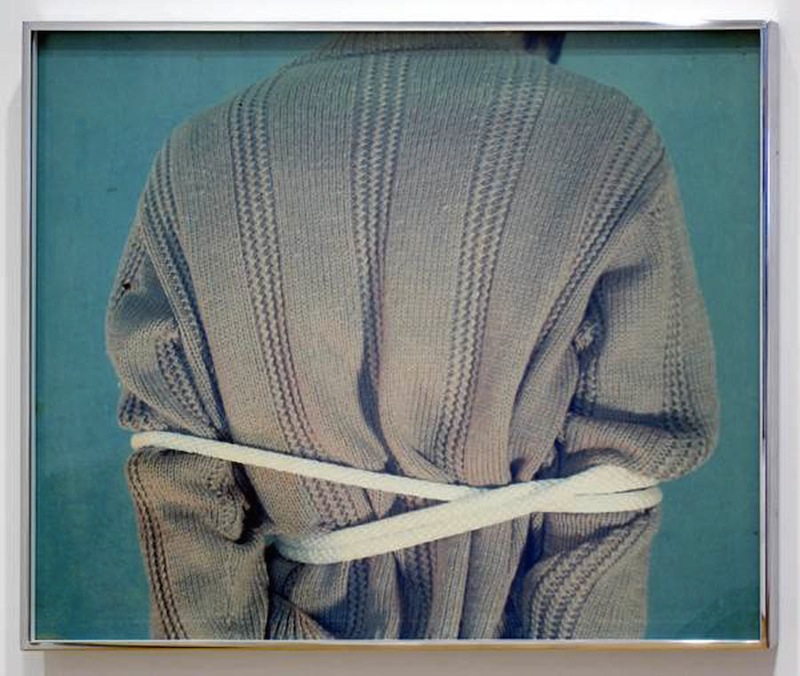

Bruce Nauman, Bound to Fail, from Eleven Color Photographs, 1967-1970; color photograph; AP Courtesy Sperone Westwater, New York

Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better. —Samuel Beckett, Worstward Ho (1983)

Artists are no strangers to failure. Despite our persistence, we don’t always end up doing what we intended. Somewhere down the line, our initial plans are rendered irrelevant and our designs come undone, scattered by unnamed processes.

It’s not just about waiting for the happy accident. Failure has its rigors. It is not something experienced only by beginners, nor is it something to get past. Failure is a lifelong commitment. As our dedication to failure increases, our understanding of the meaning and value of failure changes. Gradually, we learn to give ourselves over to failure. We come to see that our best works rise from our most profound failures and that by failing utterly and repeatedly, we will stumble into as-yet-unimagined exigencies of work and play, even as we continue to fail.

According to those who are seasoned at failing, failure is not only inevitable but also necessary. We human beings need to fail, and we need to do so often.

Fail again. Fail better.

Samuel Beckett’s admonishment to fail better may not resonate with many people. Perhaps it comes out of a twentieth-century moment of urbanity, ferment, rigor, and wit now lost to us. These days, we routinely disavow our failures, ignoring them while in hot pursuit of malformed ideas of success. Failure, of late, is highly underrated.

In reassessing the value of failure, we might consider Princeton computer scientist Ed Felten’s expression “the freedom to tinker,” by which he means the freedom to get under the hood, to learn from mistakes and failures as we play with and modify our work. By embracing our freedom to tinker, we may fully inhabit the experimental, investigative mode-of-being that is kept alive through repeated failures.

And so, the freedom to tinker is predicated on being and feeling free to fail. We must not self-censor from a sense of shame and decorum or from fear of legal repercussions. In being free to fail, we exercise a certain right to free expression that many of us have come to take for granted.

Recently, while thinking about the freedom to fail, I came across an article in Blouin Art Info about the emerging Brooklyn artist Lauren Clay and the complaint leveled at her by the estate of Abstract Expressionist sculptor David Smith (1906–1965):

“An exhibition of the 31-year-old artist’s work was scheduled to open at the Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, NJ, on October 18, but due to allegations of possible copyright infringement by the estate of Abstract Expressionist sculptor David Smith, that show may not go on.”

Left: Lauren Clay, Cloud on single-mindedness, 2012, paper, acrylic, 30 x 24 x 12 inches. Right: Lauren Clay, No side to fall into, 2012; acrylic, paper, wooden armature; 18 1/2 x 7 x 3 inches. Courtesy the artist and Larissa Goldston Gallery

“Clay’s exhibition was to include seven sculptures that reference Smith’s Cubi works—his looming welded-steel assemblages of delicately balanced geometric shapes with brushed gestural surfaces. Unlike Smith’s austere sculptures, which are eight-to-ten feet tall, Clay’s works are colorful, mostly smaller tabletop iterations, roughly 18 inches tall, and are made from materials like papier-mâché and hand painted faux woodgrain.”1

Well, this certainly wouldn’t be the first time that an artist’s estate aggressed a living artist. Indeed, over the years, the phrase “artist’s estate” has become synonymous with overreaching. And while this particular instance may seem overblown, it is consistent with the positions that usually come to bear in these conflicts.

In this instance, the remedy sought by the estate’s copyright representative, the licensing organization VAGA (Visual Arts and Galleries Association), included putting the offending works under “house arrest,” meaning that they could not be shown or sold. Robert Panzer, executive director of VAGA, is quoted as saying, “What [Clay] did was make them look just like the original…We don’t think it’s transformative enough.”2

A number of intellectual property (IP) lawyers weighed in. Nicholas O’Donnell, writing for Art Law Report, states, “[T]he Clay [sculpture] seems more derivative than transformative. If I sold a ¼ scale Andy Warhol poster that was originally a silkscreen, I would hardly expect to get away with it.”3

But are Ms. Clay’s sculptures equivalent to posters? One cannot help but wonder if Mr. O’Donnell is aware of Rachel Lachowicz’s work, or Sherrie Levine’s appropriations, or indeed the work of so many contemporary artists that explore feminist, post-minimalist, and conceptual themes.

Rachel Lachowicz, Cerulean Blue (Warhol), 2012; mixed media: pressed eyeshadow, aluminum; 24 x 24 inches. Courtesy Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento, on his art-law blog Clancco, goes further to malign Ms. Clay’s work, questioning how their “tired, cliche, and essentialist critique promotes the progress of anything other than piracy.”4

These remarks, when taken together, are aggressively dismissive, perhaps by rote, offering scant insight to the subtleties of copyright and fair use when it comes to the current contemporary art landscape. It makes me wonder if lawyers are uniquely ill-equipped to advocate for artists and others who traffic and sometimes revel in unremitting failure. After all, it’s not clear how one might acknowledge and embrace the tenets of failure while under constant pressure to win.

Clearly, not everyone can succeed at failure.

Eventually, I discovered a few wise words offered by Alfred Steiner, a lawyer who is also an artist. In the comments section of the aforementioned Clancco post, Mr. Steiner points out that Ms. Clay is a woman, and the sculptures in question were made from materials traditionally associated with craft and femininity:

“[Clay’s works] are based on sculptures made by a man from a material (stainless steel) traditionally associated with masculinity, using techniques also traditionally associated with masculinity (welding). At least that aspect of the commentary is clear. Who knows what else might be contained in the work. Smith’s estate is harmed in no way—nobody would buy one of these instead of a Smith…Not allowing [Clay] some room to play with art history would be chilling and not worth the trivial (assuming it exists at all) effect that the works might have on the market for derivative works based on Smith sculptures. When you balance cultural value of allowing artists room for free play with the market harm to the copyright owner, there really is no question. Not only should fair use apply here, but as unique works, they should be protected by a safe harbor to prevent harassing claims from overzealous copyright owners.”5

But let us take a step back. We can agree that the artist David Smith is a towering figure, his giant steel sculptures doubling as monuments to his success. His works therefore function as monumental both in the art-history narrative and in the world of art commerce. By contrast, Ms. Clay’s works are decidedly “unmonumental”: they are handmade and diminutive. Hence, the argument made by the Smith estate, VAGA, and any number of IP lawyers might be broken down as follows: How dare this unknown woman artist besmirch these ineffable works of male monumentality, rendering them in a decidedly anti-minimalist, funky-junky aesthetic, and—perhaps the worst offense—in the abject medium of “chewed paper?”

Regardless of whether or not Ms. Clay’s works fail as artworks, we can probably agree that the message and sensibility they project is antithetical to that of David Smith’s Cubi series and his work as a whole. In being antithetical, these works are certainly not too similar; they are about as different as can be.

David Dodde, Fleurs et Riviere, 2013. La Grande Vitesse (Alexander Calder, 1969) as substrate; 43 x 54 x 30 feet; 1,500 magnets, 18 flowers, and 39 leaves, hand-cut. Photo: Brian Kelly

So, while the notion that small, colorful, chewed-paper sculptures could in any way threaten Smith’s legacy or his market is laughable, Ms. Clay’s works are threatening, but only because they thumb their noses and poke a little fun at macho, self-important, Ab-Ex sculptures. When Ms. Clay unwittingly parlayed her works by planning to display them in a group exhibition, she upped the ante just enough to agitate the estate lawyers, who emitted their flurry of documents and eventually struck a deal.

This points to the fact that on some level, Lauren Clay’s sculptures are terribly successful—all too successful. I hope that she will be able to move on from this rather jarring, if strangely illuminating, unintended success, so she may continue to play and tinker and maybe even fail some. She apparently didn’t fail hard enough this time. She will have to try again. Fail again. Fail better.

________

1 Rozalia Jovanovic, “David Smith’s Estate Demands ‘House Arrest’ for a Young Artist’s Works,” Blouin Art Info, March 10, 2013.

2 Jovanovic.

3 Nicholas O’Donnell, “Lauren Clay, the David Smith Estate, David Dodde, and Fair Use: Are We Learning Anything?” Art Law Report, October 18, 2013.

4 Sergio Muñoz Sarmiento, “Artist and Smith Estate Settle Copyright Dispute,” Clancco: The Source for Art and Law, October 15, 2013.

5 Alfred Steiner, comment 29293 of “The Perils of Copying David Smith Sculptures,” Clancco: The Source for Art and Law, October 4, 2013.