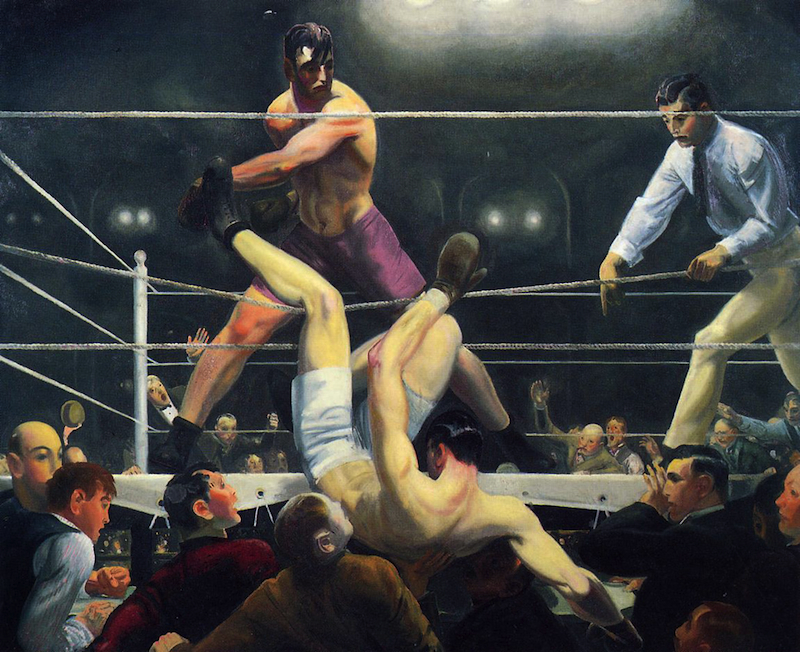

George Bellows, Dempsey and Firpo, 1924; oil on canvas; 51 × 63 ¼ inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art

In September 2013, in the sold-out MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas, the boxer Floyd “Money” Mayweather, Jr. stepped into the ring to fight the undefeated Saúl “Canelo” Álvarez. A longtime boxing fan, I was watching and rooting for Canelo, the 23-year-old redhead from Mexico. I wanted to see him do what Mayweather’s previous forty-four opponents could not: knock him out cold. In theory, it should have been an easy win for him: throw vicious left hooks to Mayweather’s body and watch him crumble. After all, Canelo is bigger and thirteen years Mayweather’s junior. But Mayweather had his own plan: deliver hard, pinpoint punches to the chin, nose, and temple, and throw them lightening-quick. He did more than just beat Canelo; he destroyed him and so outclassed his opponent that it looked like a grown man whipping a boy. By the time Canelo threw a punch, Mayweather had already delivered a blow to his nose and was standing on the other side of the ring. That’s a feeling I identify with all too well as an artist.

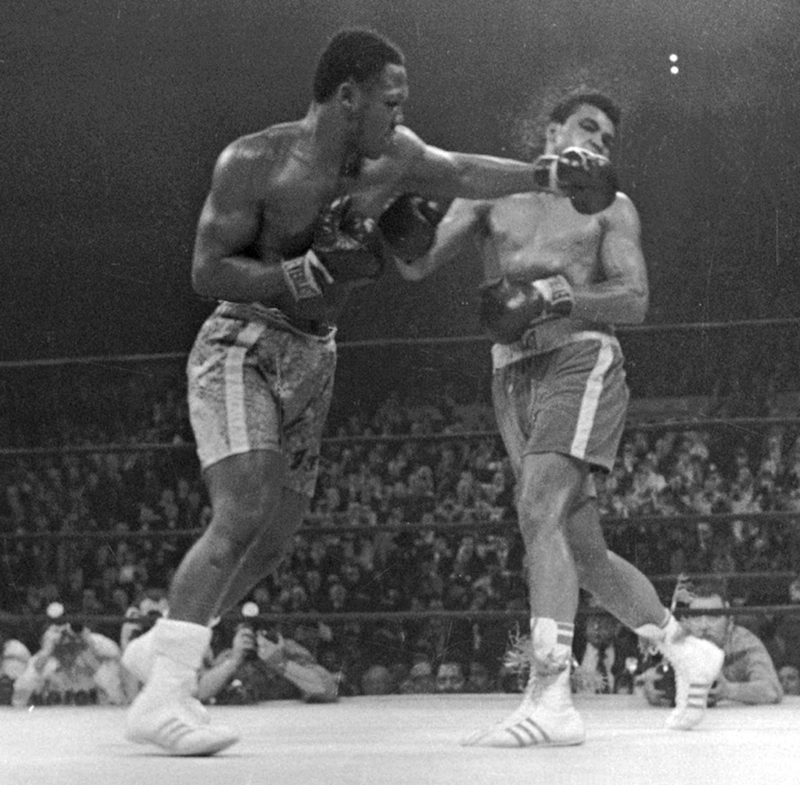

Manny Pacquiao following a devastating right-hand counterpunch delivered by Juan Manuel Marquez. Courtesy Al Bello/Getty Images

On the surface, the life of a prizefighter appears quite different from the life of an artist. The fighter deals in aggression; his sole aim is to render his opponent unconscious. It is a brutal trade, a blood sport. By contrast, the artist’s mission is to make things or create situations that affect people emotionally and intellectually, not necessarily inflicting bodily harm in the process. Where the fighter and artist do meet is at the intersection of passion and isolation. The fighter, like the artist, is compelled to stand alone, independent, outside the system, without an organization to fall back on. Art making and boxing are solitary trades for solitary souls.

Boxer at Rest (detail), Greek, Hellenistic period, late 4th–2nd century B.C.; Bronze inlaid with copper; H: 50 inches. Museo Nazionale Romano – Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, inv. 1055. Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen

Imagine what a fighter must feel like as he walks into the ring alone, stripped to the waist with nothing more than his skill and heart to protect him, as his doppelganger stands in the opposing corner waiting to beat him senseless. The closest parallel I can draw is the feeling of being in my studio, alone, facing the computer screen or blank sheet of paper. Hollywood stars do not sit ringside here. Those seats are saved for doubt, anxiety, and indecision that neither noise nor silence can subdue. No matter how difficult, my experience doesn’t involve the physical pain that fighters endure in the ring, of course. One blow to the head can cause a fighter’s brain to hurtle against the back of his cranium. To be honest, I’ve never even been punched in the face. But I have caught a metaphorical beating or two in my studio.

Film still from Cutie and the Boxer, 2013. Left: Noriko Shinohara. Right: Ushio Shinohara. RT 82 minutes. Director: Zachary Heinzerling

Since the age of eighteen I have devoted my life to making art. As a student, I wanted stardom: blue-chip gallery representation, museum shows, and world travel. Those goals changed as I matured and simply wanted to do what I liked and make decent money doing it. Like Canelo, I had good training. Mine came in the form of a BFA in painting and drawing and the Bronx Museum’s professional-development program, Artist in the Marketplace (AIM). Museums and galleries have exhibited my work, and yet many of my goals elude me. As I write this, I am sitting in my studio, located in the small bedroom of an apartment that I share with my wife, Marie, and our 21-pound beagle mix, Hammer. I have no gallery representation, no exhibitions lined up—none, zilch, zero. And my income streams have dried to a trickle. I can identify with Canelo in the sense that no matter how hard he tried, he failed to implement his game plan.

Muhammad Ali (right) takes a devastating left hook from “Smokin’” Joe Frazier (left) during the “Fight of the Century,” March 8, 1971. Associated Press

I have often measured my artwork and career according to a success/failure paradigm. On one side is success, where my work shows, sells, or receives critical acclaim. On the other side is failure, the absence of these events. This black-and-white perspective leaves little room to breathe, much less thrive. On the cusp of my fortieth birthday, I have to ask myself, as Julia Cameron suggests that artists do in the face of failure, now what?1 Perhaps there is an answer in the fight game: be resilient. Canelo lost to Mayweather in front of millions of people, but he isn’t quitting. He’s picking up his gloves and going back into the ring.

________

1 Julia Cameron, The Artist’s Way (New York: Putnam, 1992).