Banksy, Better Out Than In, New York City, October 2013. Photo: Scott Lynch

Failure is seductive. Just take a look at the narrative arc of any of the most-watched soap operas, across different languages and cultures, to see that family discord, marital breakdown, personal incompetence, and financial problems are what we are drawn to witness in droves. Failure indulges morbid fascination with what went wrong in a situation while offering a soapbox for the critics (never in short supply) to tell us what the remedy is. Nowhere is this equation more evident than in the debates over urban spaces.

To wit: Banksy, Manhattan’s unofficial artist-in-residence during October 2013, offered his two cents on the new World Trade Center designed by Daniel Libeskind with David Childs of the firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM). (The New York Times declined to publish an op-ed offered by Banksy that, among other shaky generalizations, suggested the new building was “vanilla” and that it “looks like something they would build in Canada.”) The graffiti artist echoed a long line of other voices—those with experience in urban planning and architecture, those who lost loved ones on 9/11, and many others who have nothing more than their individual subjectivity to offer—who have condemned as an unmitigated failure one of the most costly twenty-first-century interventions in urban space.

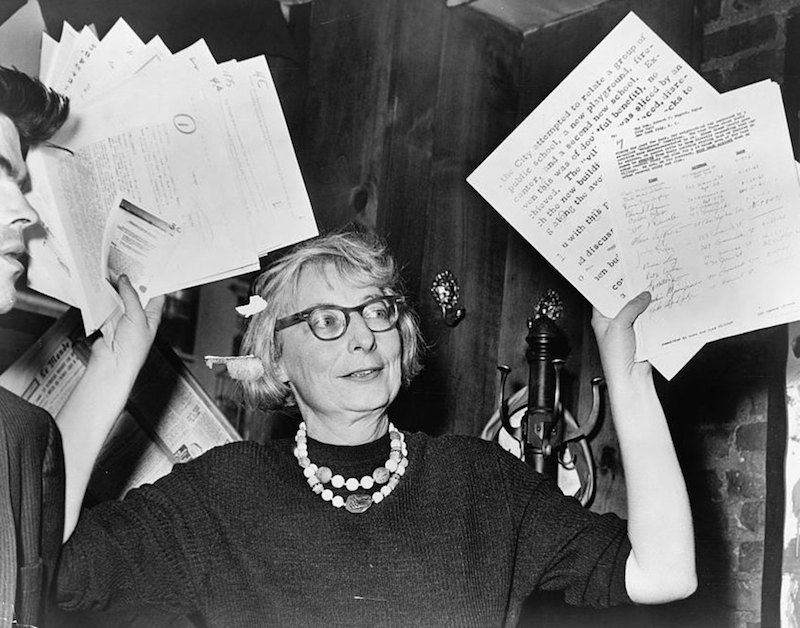

Mrs. Jane Jacobs, chairman of the Committee to Save the West Village, holds up documentary evidence at a press conference at Lions Head Restaurant in New York City. Photo: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ-62-137838

Repetitious as they may be, these cries express a fundamental right. Our cities are shared spaces, places that—as Jane Jacobs so rightly told it in her 1961 masterwork, The Death and Life of Great American Cities—need everyone in them to participate in their creation. Jacobs was first mobilized to write about urban space as an activist in response to its wholesale takeover by, among others, New York City’s “master builder,” Robert Moses, who flogged public lands to private interests and racially segregated them in the process. Jacobs’s bugbear was not Moses alone, however. She lamented the broader inability of mid-century architects and city planners to respond humanely to urban populations: “The pseudoscience of planning seems almost neurotic in its determination to imitate empiric failure and ignore empiric success.”1 Others agreed. It might be argued that the architectural critic Charles Jencks wrote the most famous line of his career a few decades later—sounding the death knell of the modern movement on July 15, 1972—when he equated failure and urban space in his infamous obituary for the Pruitt-Igoe complex.2

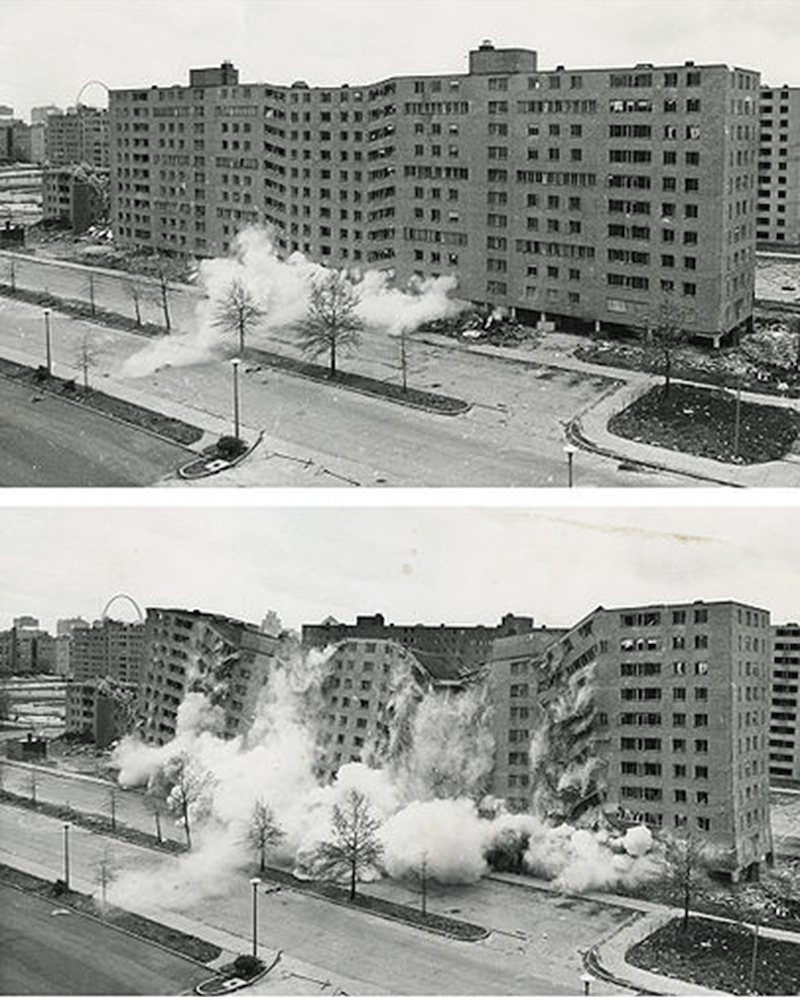

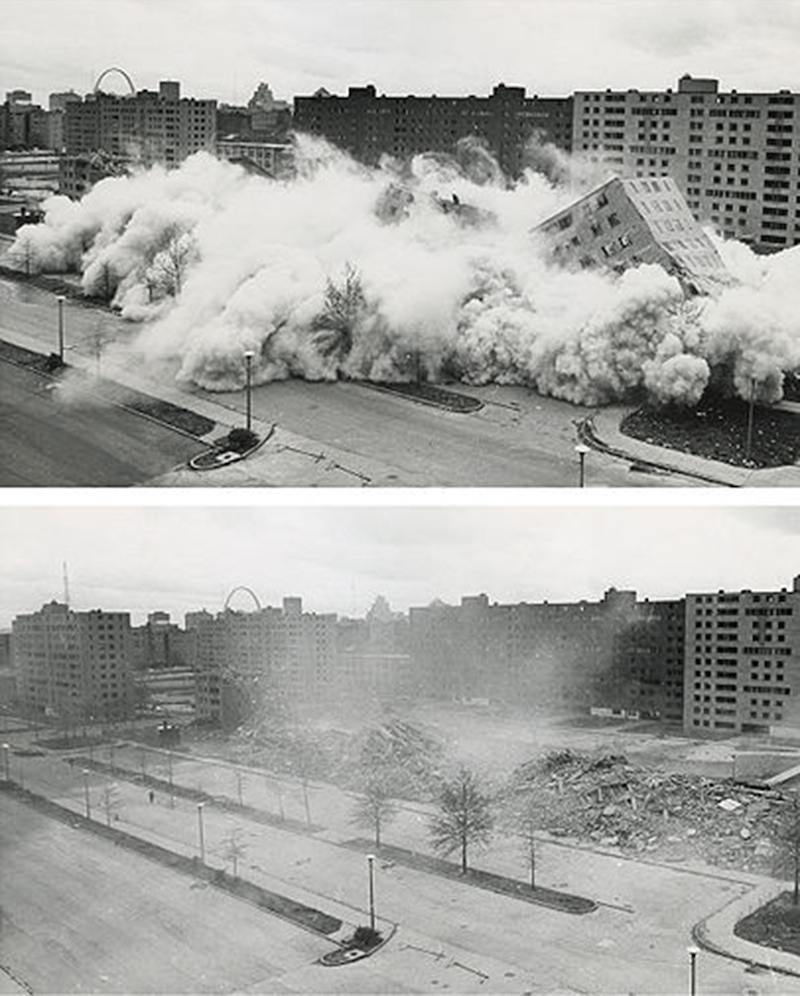

Demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St. Louis, Missouri, 1972. Photo: US Department of Housing and Urban Development

And that, for the most part, has been the story for the past fifty years: Planners and architects were monsters. They caged the urban poor. They failed.

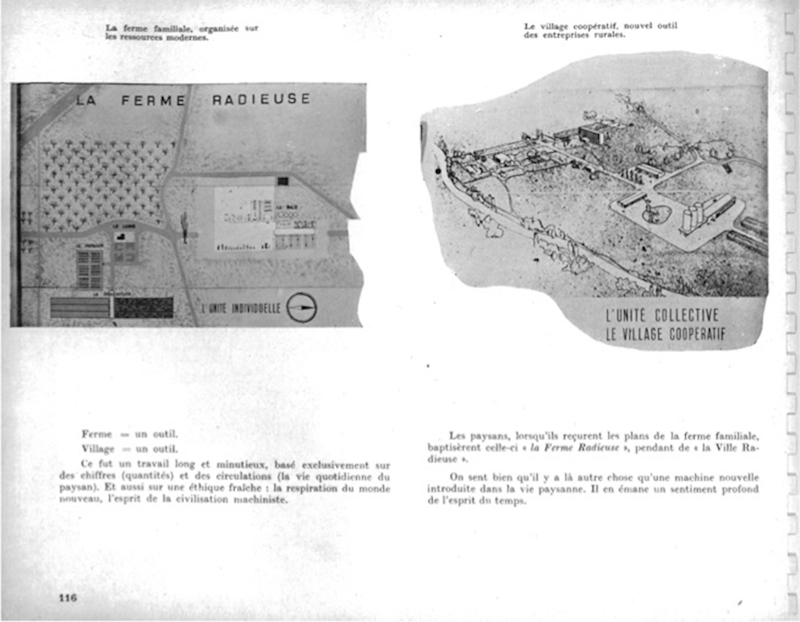

The grandfather of this conversation is, of course, Le Corbusier, whose legacy of urban plans such as the Ville Contemporaine (1922), Plan Voisin (1925), and the Radiant City (1933–37) has been mythologized and often maligned. Collectively, such plans have been used to condemn the architect, during his life and posthumously, on formal and social terms as the progenitor of reviled “towers in the park” that proliferated across postwar Europe and North America and gave rise to imitations like Pruitt-Igoe.

Demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St. Louis, Missouri, 1972. Photo: US Department of Housing and Urban Development

Yet in the past few years, paralleling a coincidental reinvigoration of urban space by the Occupy movement, architectural historians, urban sociologists, and architects have provided nuances to this particular narrative of Modernism’s failures. Without understating the mishandling of postwar public spaces and building projects undertaken in the name of Modernism, new voices have been given room to reflect: the residents of urban spaces.

A recent documentary, The Pruitt-Igoe Myth (2011), quite powerfully reassessed the received critique that the architecture and its inhabitants had caused the demise of the project and others like it. Instead, in compelling oral histories, former residents trace a more complicated route—through the Great Migration, the initial success of social housing in the postwar period, “white flight,” shrinking tax bases, and inhumane local welfare policies—demonstrating the multilayered network that contributed to Pruitt-Igoe becoming a slum. The residents don’t shy away from what went wrong, but they take issue with its oversimplification, as well they should. No one’s home is uncomplicated, cut and dried, a success or a failure.

Heidrun Holzfeind’s documentaries Za Zelazna Brama (2009) and Colonnade Park (2011) also tell stories of high-rise urban housing, in Warsaw, Poland, and Newark, New Jersey, foregrounding the lived experiences of tenants. This approach replaces the reductive binary of failure/success with the nuances of individual hopes, dreams, disappointments, and connections. Owen Hatherley’s populist recuperation of Brutalism in A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain (2010) and Nicholas Dagan Bloom’s richly academic rethinking of social-housing projects in New York in Public Housing That Worked (2009) provide reconsiderations of the problems of urban housing, a topic that has until this point been jettisoned as beyond hope.

Le Corbusier’s utopian ideas about cities became springboards for anonymous city-council architects. The Radiant City (and Village and Farm) were adapted and realized in far-flung places like Arizona, Glasgow, and Warsaw, places in which “Corbu” never set foot. Tracing these architectural translations means understanding the complexities of intercultural relationships between architects, local and national administrations, residents, and planners (a methodology that has gained traction in recent exhibitions on Corbu at the Canadian Centre for Architecture and the Museum of Modern Art, New York). Rejecting the polarizing account of Le Corbusier as a twentieth-century visionary, or as a scapegoat for the perceived successes and failures of the modern movement, is decidedly less sexy but ultimately more productive.

Le Corbusier’s The Radiant City, first published as Ville Radieuse, 1933. Image taken from Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret: Oeuvre Complète de 1934-1938, Volume 3 (Les Éditions d’Architecture, 1964).

Shortly before his death in August 1965, Le Corbusier began to collate two decades of his writings, which resulted in the understudied volume, Mise au point (1966). It is an idiosyncratic and highly personal summation of his life and work that offers a subtler alternative to the contrary image molded by critics and accepted by the public. The architect outlines what Jencks later characterized as the “tragic view” of his career, lamenting a life devoted to the study of housing that was, in Le Corbusier’s eyes, underappreciated by the French government and the wider public.3 Shunned in the postwar rebuilding of Paris, the architect only partially achieved his Radiant City in the form of the controversial Unité d’Habitation housing block in Marseille (1947–52). Reflecting on the fact that his first and only French governmental commission was granted at the age of sixty, Le Corbusier begins and ends Mise au Point by noting that in the end “nothing is transmissible but thought, the fruit of our labors.”4 This is a prescient epitaph given that his ideas concerning standardized high-density housing and urban planning were far more influential than any of his built projects. It seems that Corbu called himself somewhat of a failure, despite what the historical record might now argue. I can’t think of a better contradiction with which to continue the project of redefining so-called architectural failures and really getting to grips with the grey areas that constitute our own lived experiences in urban spaces.

________

1 Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House Digital, Inc., 1961), 183.

2 Charles Jenck, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1977).

3 Charles Jencks, Le Corbusier and the Tragic View of Architecture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973).

4 Le Corbusier, The Final Testament of Père Corbu: A Translation and Interpretation of Mise au point by Ivan Zaknic, ed. Ivan Žaknić (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 41.

Pingback: Letter from the Editor | Art21 Magazine

Pingback: Complaining about architecture: easier than talking about race