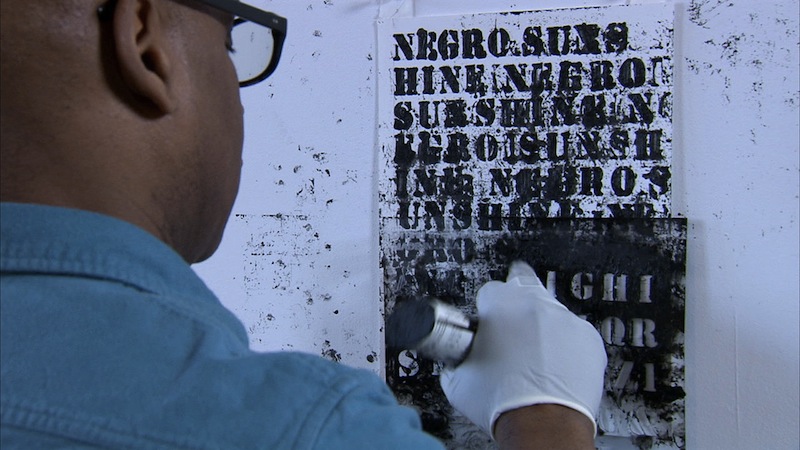

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 6 episode, “History,” 2012. © Art21, Inc. 2012

“The path of least resistance and least trouble is a mental rut already made. It requires troublesome work to undertake the alteration of old beliefs.” ―John Dewey1

“The muse of invention doesn’t exist; you just have to work. It’s a job, and you just have to come. For me, usually, it happens at the last minute of the last hour: I’m utterly exhausted, and I thought it was a wasted day, and then something happens.” —Arturo Herrera2

How can we help students fail productively?

Failure is a bad word in education. It means we didn’t pass the test. It means our teachers are sub-standard. It means our percentages are below national and international passing rates. And the litany goes on. But in most creative contexts, failure is essential. It is a central aspect of creating anything worthwhile, rethinking old assumptions, or critiquing social or institutional norms. In any field, failure fosters new possibilities: the solution we didn’t know was possible, the idea born of a paradigm shift, the singular and original statement. To the artist we often ascribe the audacity and bravery of someone who is either bound to fail or bound for ultimate glory. Failure is always seen as an either/or scenario rather than a constant underlying force. Many artists talk about the role of failure as a productive force in their work. Art21 artist Glenn Ligon describes how he started making his iconic stencil-letter paintings: It was supposed to be neat; the oil stick was supposed to stay inside the lines, but it didn’t. And it took him six months to realize that this failure was actually more interesting than the original idea.

Arturo Herrera describes failure as swimming (productively) with sharks: “When dealing with new works or new techniques, it’s bound to fail. But it is necessary. It is essential for me to go into this state. It’s like swimming in water full of sharks. Just go with it.”3

The space to experiment, fail, try again, rethink an idea, perhaps throw it out, start over, and then do it all over again, over a long period of time, is an anathema in education. It exists in only the most rare schools and classrooms: those that value process over product, play and inquiry over facts and dates.

In popular education, learning is understood as being synonymous with difficulty, with pushing past your comfort zones and the things you already know or believe—that sticky and unsettling place when you, like Dorothy, leave Kansas—when you have to reorient your previous assumptions and common-sense notions.

Teaching students how to think, not just what to think, is becoming more common as a progressive educational mantra. But how do you do that? And how quickly can we turn around a system that is based on rights and wrongs, and successes and failures, in the strictest senses of those words? How do we reward experimentation, spontaneity, and risk taking? How can we help students see the infinite ways to solve a problem, to seek an answer, and to construct an opinion? As John Dewey told us long ago, we learn by doing, but we also learn by examples, many of them.

Following a screening of the film William Kentridge: Anything Is Possible at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Kentridge talked briefly about failure. “We could have a long discussion about the need for failure…a series of less-bad solutions. Some get reprocessed. Some get thrown out.

What would be interesting is having a room of failures.”4 What would a room full of failures look like? Certainly Kentridge’s failures would likely appear far less dismaying than those of many other artists. But what if we asked students to curate a room full of failures—to proudly array the detritus of their processes and to reflect on their intentions and implications—to connect the messiness of not knowing with finally coming to a point of knowing? To hold sight of process in the context of achievement—and to have a healthy understanding of how to pick yourself up and keep going, even after all the mistakes, missteps, and mishaps?

Well then, Toto, we would not be in Kansas anymore.

________

1 The Later Works of John Dewey, Volume 8, 1925–1953: 1933, Essays and How We Think, Revised Edition, p. 136.

2 “Arturo Herrera: Failure,” Art21 Exclusive.

3 Ibid.

4 Quote from a post-screening discussion at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, September 12, 2013.

Pingback: Letter from the Editor | Art21 Magazine

Pingback: FAILING PRODUCTIVELY: ART 21 MAGAZINE | ipad integration

Pingback: Revamping Art Education for the Twenty-First Century | ART21 Magazine