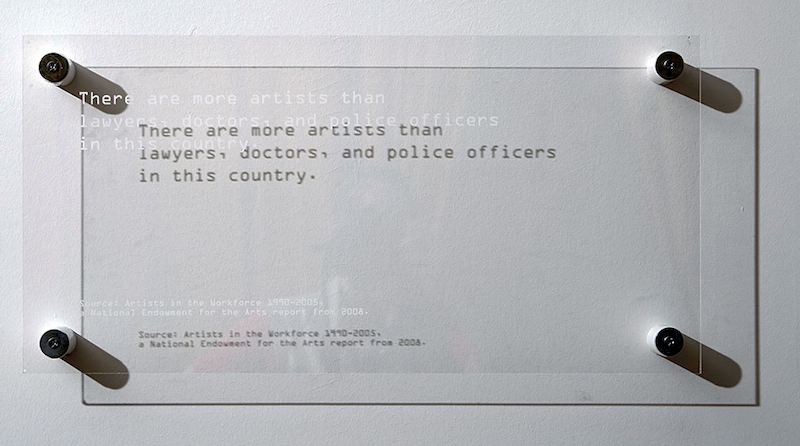

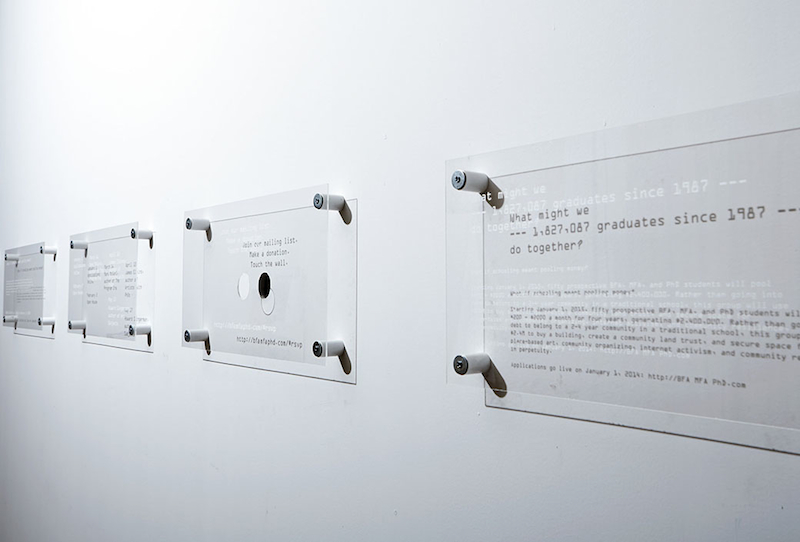

Caroline Woolard. BFAMFAPhD installation, 2013. Etched plexi and hardware; dimensions variable. Open access exhibition, https://BFAMFAPhD.com. Photo: Martyna Szczesna. Courtesy BFAMFAPhD.

Caroline Woolard, an artist, activist, and community organizer based in Brooklyn, New York, was inspired to initiate the project BFAMFAPhD following Cooper Union’s announcement last April to start charging tuition. For 154 years, Cooper Union had been among a very small number of institutions, including the nation’s military academies, to offer a free undergraduate education. In the fall of 2014, each newly enrolled undergraduate student will receive a half-tuition scholarship, approximately twenty thousand dollars per year. While the school intends to offer full scholarships to selected students with financial need, the majority of students will now pay some portion of the remaining twenty thousand dollars. A few students cried as the Cooper Union’s board chairman, Mark Epstein, broke the news in the school’s Great Hall.

Woolard, who graduated from Cooper Union in 2006, was also deeply disappointed.

Since 2008, Woolard has been researching how artists are professionalized in this country. According to that year’s census, there are more than three million artists in America. There are more artists than police officers, lawyers, or doctors in this country. Every decade, one third of that lot receives a bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral degree in the arts. From 1987 to 2012, there were 1,827,087 graduates with a BFA, MFA, or PhD in the visual and performing arts.1 Despite the recent criticism of MFA programs, these numbers are growing.

Many professional degrees for creative fields have hefty price tags, and often artists are saddled with significant debt as a result of student loans. For example, the Rhode Island School of Design’s current tuition is $42,622 per year for graduate and undergraduate students alike. An MFA from Columbia University averages about $100,000 over two years. Given the high cost of living in a city like New York, these expenses can haunt artists in the form of monthly student-loan payments that continue for several decades.

BFAMFAPhD is an open-ended project that endeavors to unite artists in order to address the problems of their rising population in this country. The application form to join the project (available on the project’s website) states that this ongoing research and organizing initiative “visualizes the number of students graduating with creative degrees, generates dialog about our collective power, and elicits proposals for organizing efforts.” If artists opted to put their money into cooperative loans rather than tuition, this capital could be pooled for the benefit of the community. Moreover, if schooling were free, as it is in many countries abroad, artists might be granted the financial liberty to focus on politically engaging and provocative work instead of feeling pressure to create sellable, sometimes conservative, work. The initiative, its website, and its related installation and talks at the Queens Museum of Art aim to raise awareness about these issues.

The collective is currently accepting new members. Woolard believes that the first step, once artists have amassed as a group, is to understand the needs of this constituency. The resulting activities of this organization will yet be determined. Woolard explained, “This is the first phase of an organizing project, so it will lead where our collective desires and abilities take us.”2 The members will shape how the project unfolds over the next few years.

Caroline Woolard. BFAMFAPhD installation, 2013. Etched plexi and hardware; dimensions variable. Open access exhibition, https://BFAMFAPhD.com. Photo: Martyna Szczesna. Courtesy BFAMFAPhD.

Woolard, along with her collaborators, have been investigating what the collective might be able to achieve. One proposal, put forth by a member of the collective, envisions communal living arrangements for students at an alternative art school. Another option would be to create a labor union for visual artists. The Actor’s Fund was founded in 1882 to support all professionals in the performing arts, but there is no equivalent for professionals in the visual arts. The money from a collective fund could also be used to buy a building for affordable housing or studio spaces for artists. These are among the many proposals that BFAMFAPhD is currently exploring.

When Peter Cooper founded the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in 1859, his mission was to give working-class New Yorkers access to a quality education with no financial burden. As this mission has been eroded, a community of thinkers in BFAMFAPhD—an imaginative school of thought—is getting organized. The project is assessing the collective powers of artists in this country and forming an invaluable cultural front. Woolard said, “I don’t know yet where BFAMFAPhD will go, but we have a lot of potential.”3

BFAMFAPhD members include Annelie Berner, Luis Daniel, Michele Graffieti, Ann Chen, Brian House, Lika Volkova, Ben Lerchin, Alex Mallis, Vicky Virgin, Jeff Warren, Mira Rojanasakul, Agnes Szanyi, and Caroline Woolard.

On May 17, 2014, 3–5 pm, Howard Singerman, the author of Art Subjects, will join BFAMFAPHD in a conversation about his work and collective power at the Queens Museum of Art.

________

1. “Data,” BFAMFAPhD.com, March 7, 2014. https://bfamfaphd.com/#data

2. Caroline Woolard in conversation with the author, February 2014.

3. Ibid.