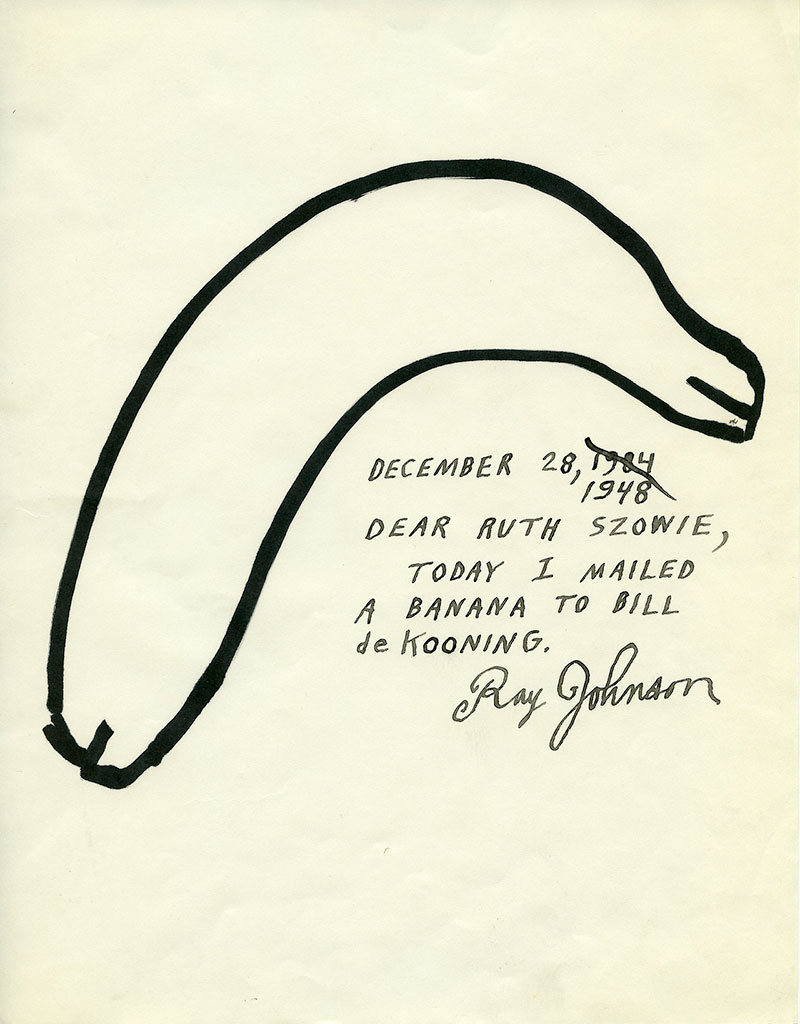

Ray Johnson. Today I mailed a banana to Bill de Kooning, 2013. Courtesy Ray Johnson Estate Tumblr. © Ray Johnson

It’s no secret that the time has come to hash out a plan for getting digital artists paid for their creative work. Our collective consciousness understands this, and yet many big unanswered questions stand in the way of a solution. In a copy-and-paste culture spurred by social-sharing mayhem, how do we create an ecosystem in which artists can earn money for their networked art while recognizing that the context of the Internet is fundamentally unlike the object-focused art market?

Recently, Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash attempted to solve this problem of digital ownership at Rhizome’s “Seven On Seven” conference by creating Monegraph, short for “monetized graphics,” a tool that uses cryptography to create a system in which ownership can be verified, thus creating an illusion of an original.1 But can ownership be satisfying as an idea or an abstraction rather than a concrete assertion of possession in which the term owning is synonymous with the physical possession of an object? And how should we critique the idea of creating scarcity online, where we have traditionally celebrated the fact that anything and everything may be endlessly redistributed through the network?

For digital artwork, context (that is, how, when, and why a viewer is accessing the work) is a key part of how a work is understood. Interestingly, it’s nearly impossible to retain control of the context in which an artwork is viewed online, and artists have proceeded with the understanding that the Internet will often carry their artwork to unknown, uncontrollable places; this is simply a fact of exhibiting art online rather than in a physical gallery. This raises a question: After an artist has created a digital artwork with the intention of uploading the file to an online network, how much of the artwork remains to be completed by its journey through and along that network? If engaging with and sharing digital art are fundamental components of a networked digital-art piece, then creating the illusion of scarcity through Monegraph’s system in order to sell digital artwork would fundamentally alter the nature of the medium.

While all digital works are not networked art, we’re in an interesting moment, when social-media platforms seem to have imposed the network across all online realms. By posting a work online (or even by showing work in a situation where it may be photographed and then shared), one surrenders a degree of ownership, and it’s possible that the work will be copied, decontextualized, remixed, or, worse, stolen. This is obvious on Tumblr, where the nature of the platform is to enable the transmission of content ownership with the click of the Reblog button. The primary vocabulary term of social media is to share, which fundamentally goes against the idea of declaring singular ownership; we celebrate (and even fight for!) the ability to endlessly amass virtual content, all for free. Bringing money into the picture is counterintuitive, mostly because the exchange of a sum of cash for a particular, singular item is counterintuitive to the way the Internet works. What types of payment systems could work with networked artworks rather than against them?

“In 1969, Ray Johnson was invited to participate in the 7th Annual Avant Garde Festival on Ward’s Island. For his contribution, he decided to rent a helicopter and drop 60 foot-long hot dogs onto the unsuspecting lawns and houses below. This performance related to a series of drawings he was then doing: traces of people’s feet. Johnson was later surprised to learn that many people ate the hot dogs, thinking they were food, not parts of an artistic performance.” Courtesy Ray Johnson Estate Tumblr.

The problems of collecting networked art are not new. In the 1950s, the Conceptual and Pop artist Ray Johnson pioneered the practice of mail art, in which he would send artworks to friends and acquaintances via the US Postal Service, asking the recipients to add to or alter his work and then send it to someone else.2 As Jeanne Marie Kusinan so aptly put it in her 2005 Contemporary Aesthetics article, “The Evolution and Revolutions of the Networked Art Aesthetic,”

[Johnson’s mail art was a reaction against] the official art world, with its institutional hierarchies and gallery elitism [representing] a fundamental move away from the paradigm of art produced to sell or own. This was art to give, send, and potentially lose or destroy by the very process of mailing.

For Johnson, the process was the art; the object was just a byproduct. As Johnson’s work shifted away from object-oriented art towards this more conceptual, collaborative form of art-making, the fact that his mail art was never supposed to be sold brought up many new questions, such as: How can one collect an object as an artwork when the work is actually a series of events taking place over time?

Compared to the problem faced by today’s digital artists, Johnson encountered the opposite: his work was not supposed to be collected in the traditional sense, but some people collected or sold the pieces created by the mail art network, regardless of his creative intention. Since physical objects existed, the official art world desired them; the allure of the art object cannot be denied, for better or worse. For digital artists, despite their desire to be considered part of the official art world, the lack of a physical artwork effectively creates an aching hole into which collectors peer, searching for some object to hold onto. While this problem is different from Johnson’s, the underlying concern is the same: What does it mean to own an artwork if the piece is not a self-contained object but rather an abstract manifestation?

While Ray Johnson’s mail art moved through an intimate network of artist friends and acquaintances, today the term networked art has become synonymous with art that moves through the Internet as a whole, via intimate exchanges or anonymous, mass-distributed websites, emails, and/or social networks. As the network has grown larger, so, too, has the networked-art medium become more difficult to pin down. Artists make use of social and digital media not only to distribute and promote their works but also to exchange ideas, find inspiration, find source material, conduct research, read and react to art criticism, and collaborate with other artists. As Brion Nuda Rosch wrote in a 2010 post for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Open Space blog, “Zuckerberg has made an interesting interactive art piece with his project called Facebook. In part it has formed into a dysfunctional meeting ground for the art world.”3 Four years after Rosch’s remark, we’ve come to a time when we’re starting to consider ways of making the networked art world’s place on the Internet less dysfunctional.

Stay tuned for Part II of this article, to be published later this week.