As we experiment with ways of bringing digital art into the fold of the mainstream art market, it’s important to think about the ways in which traditional models of collecting art are at odds with the fundamental structures supporting art of the digital age. Rather than relying on ways of making digital art more similar to physical, in-real-life (IRL) art, such as with the earlier Monegraph example in the first part of this article, we should examine examples of creative networks that are rethinking the system in ways that shake up the traditional notion of the arts patron.

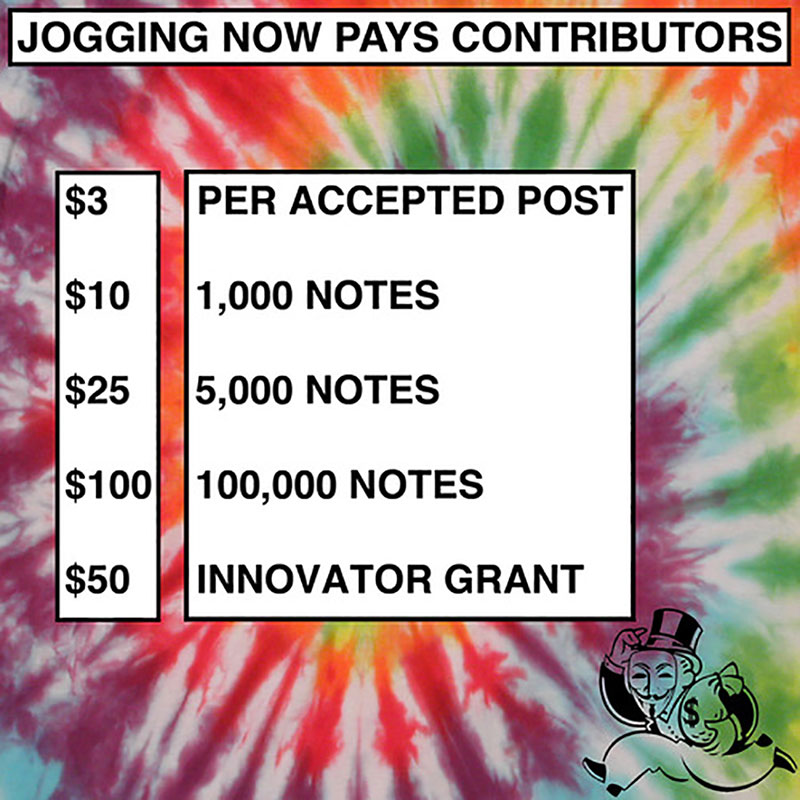

The Tumblr site The Jogging is very aware of the network in which it exists, as both the aesthetic of the content it publishes and the artists it showcases seem to live and work by the laws of the social media age. I’m particularly interested in the recent announcement of a new artist-compensation system, rewarding those who submit artwork to the site with micro-payments based on how far the submitted work moves through the network (that is, how many likes and reblogs the post accrues). The idea of payment by popularity is fascinating, as it mimics the traditional art market while inventing a new value system based on the amount of enthusiasm shown for any given work by the engaged followers.

Similarly, the networked-art platform New Hive is interested in testing models for sharing and supporting creative expression online. In Proof of Work, a recent exhibition that I co-curated, New Hive participated by showing work in the form of web pages by the Internet artists Molly Soda, Alexandra Gorczynski, and Labanna Babalon. While other artworks in the show were available for sale in the traditional sense, viewers who appreciated a particular New Hive work were requested to consider leaving a tip for the artist via Venmo, a payment app. This presents an intriguing idea: the desire to own a tangible object is superseded by an appreciation of creative work and an acknowledgement of the fact that artists who do not create physical, object-based artworks still need to make money. The tip-your-artist proposal recognizes that these works are in a sense public, and if a viewer gets something from the artwork’s existence, she should do her share to support the work’s creator(s). If cultural consumers take online artwork for granted—thinking of it as a public utility, almost—can a payment system be put into the scenario without jeopardizing the flow of information and the nature of digitally networked artworks? The public radio system of pledge drives wouldn’t be right for the digital-art world, but perhaps there is something in that model that might be adapted, to remind people of the intrinsic cost behind something that appears to be free.

Another potential model for creating financial viability for digital artists is the platform Depict, which allows users to purchase an edition of a digital artwork to add to their virtual collection. Works that users have paid for may be streamed to screens, thus bringing the digital work into the physical realm in a more traditional, image-on-the-wall context. In this system, artists are able to set the price and the number of digital editions that may be sold, which brings some degree of scarcity into the equation while allowing for a network of buyers to own the same work. In this instance, when one “owns” the work, one only owns the right to stream the work to a screen; as soon as the stream is stopped, the work is gone until the next time a collector thinks to conjure it by streaming it. The value of the artwork depends on the structure and longevity of the platform, prompting another concern: When there’s nothing tangible to anchor the artwork to reality, there’s nothing to stop it from dissolving into nothingness, and it’s hard to bring financial viability to this model.

As we move into a future in which digitally networked art will become more prevalent, it is interesting to look at another feature of the New Hive site, the Remix function. Unlike Tumblr, which allows a user to reblog an artwork to her personal microblog in order to virtually accession it into her archive of content, New Hive lets users digitally manipulate another artist’s work—it is a digital version of Ray Johnson’s mail art process, in which ownership is shed over time as the work becomes a communal project. Since fifteen percent of all Internet users remix online material into new creations, this Remix button takes appropriation to the next level, acknowledging the fact that the network has become so collaborative that ownership of a digital artwork can be as fluid as the Internet itself.4 While we work to define systems for paying digital artists, we also need to think about modes of attribution that reflect the collaborative spirit of the Internet and recognize artists as creators who own the ideas behind the works that they bring into the world.

While Ray Johnson did not wish to see his mail art exchanged for money, today’s digitally networked artists do need to be compensated in order to sustain their creative practices. In a world where ownership of artwork is confusing for both the creators and the collectors, we need to imagine ways in which making and sharing art can be financially viable. It may mean a complete reassessment of the fundamental systems on which the art world has been built.

Pingback: From Mail Art to Tumblr: Making the Future ’Net Work, Part I | ART21 Magazine