Simone C. Niquille. Facebay, 2012. Screenshot of website, facebay.cc; dimensions variable. © Simone C. Niquille

Simone C. Niquille, is a graphic designer and researcher whose work instantly grabbed my attention. Niquille’s work has a bold style and addresses important issues of our time, such as facial recognition, identity politics, and networked optics. Her work was recently exhibited at TodaysArt Festival in The Hague and de Appel Arts Center in Amsterdam, and has been featured in Wired, DIS, The Atlantic, and other publications. Niquille worked with the research studio Metahaven on their recent exhibition Black Transparency and is currently part of a design and research collaborative called Space Caviar in Genoa, Italy. Niquille’s work confronts a present that many thought wouldn’t exist for some time. Social media with built-in facial-recognition and biometric software still sounds futuristic, but it’s already here. I chatted with Niquille via Google Hangouts and email about where she sees social media going, especially in light of recent revelations about the technologies at hand.

Ben Valentine: Briefly paint possible scenarios for the future of social media, one being the future you hope for and the other being the worst possible future you can imagine.

Simone C. Niquille: The worst scenario would be one of social media shedding the social and becoming solely media, an accumulation of data-dissemination channels. In this future media, there wouldn’t be users but contributors. No signup necessary; anyone’s contribution would be greatly valued. Lost passwords would be a trait of the past, solved with biometric-data passwords. Signing in would be obsolete, wiped from the collective vocabulary. A connection to media would be certified free, verified stable, and virtually invisible. Less about connecting and more about understanding yourself as a first step before being able to connect, media would offer a Dr.-Phil-on-steroids self-analysis service. Media would be so eager to help you understand your behavior that it would take over broadcasting for you. Posting would become redundant: what you were going to post would already be uploaded for you. Once in a while there might be glitches, with media posting your next coffee run before you even knew it—but what a handy reminder that would be, of you wanting a coffee. Media will know you so well that it will be your personalized social self. You and your media, forever. The hopeful scenario, one I strongly believe in, would be one of stressing the social, one that separates functions and builds platforms to perform simple tasks well and securely. Twitter’s addition of a tagging function and update of user profiles to look like Facebook’s younger sibling are destructive developments. It would be better to have stripped-down options and separated services, a return to community building, connecting, and sharing, instead of the current obsession with identification and personalization.

BV: With the emergence of all of this collection of metadata, as well as these ideas of the quantified self, questions arise about how to algorithmically define or target a person. Much of your work, especially Realface Glamouflage and Facebay.cc usurp this stringent data-oriented understanding of self, allowing for more play to come into the mix. Given how much data governments and ad agencies collect to quantify us, what decisions can actually be drawn from that data? I fear this type of data-collection understands humans in a very black-and-white understanding of identity, which is deeply problematic.

SCN: What is important in the discussion of the quantified self and the creation of a database of affinity is the human need to identify, categorize, and name. This need predates today’s technological abilities, though, and is an instinctive trait. What cannot be identified—the unknown, the dark—is viewed as a threat. The faceless becomes the enemy. In this case, veils do not evoke an appreciation of mystery; they must be destroyed and transparency provided for the sake of safety. Representations of biometric identification of the body and its parts have in turn become part of the aesthetic vernacular of the War on Terror.

For some time, while I was in college, I was into explosives and small detonation devices. I would cast plaster sculptures and photograph them being blown up. I needed to learn about explosion velocities to calculate the power of discharge and shattering. To do this, I would check out books from the university libraries and spend hours on online forums. The results of this explosives-information-gathering quest are stored somewhere, hopefully added to my database of affinity. As an author, taking on different personas to create a narrative, conducting research and literally creating different identities, is essential. In the current state of data harvest and storage, those fictional characters would all be linked to one persona, the one corporeal person performing the searches. What a perfect way to stir confusion into your data set, to dazzle the affinity. I don’t believe in hiding but rather in living in a way that frees you from restrictive and identifiable bounds.

BV: We talked a little while ago about Vanessa Stiviano, the model responsible for recording Donald Sterling’s racist rants, which ultimately lost him ownership of the Los Angeles Clippers. Stiviano has had some amazing outfits in response to an intense media gaze. Talk more about identity and the idea of introducing noise into our information ecosystem?

SCN: Yes, exactly. Bring the smoke machine. I recently came across a photo of Vanessa Stiviano wearing a large reflective visor covering her face. What is great about the photo is that while Stiviano’s face is covered, the people around her wear caps embroidered with her name. It’s anonymous aesthetics as luxury. Rather than anonymity, the visor provides exclusivity. With her human name-tags beside her, Stiviano’s face becomes a rarity, her identity obvious. It’s similar to Michael Jackson’s past attempts at covering up his kids, most famously with a burka while getting into a car in Bahrain. The act called far more attention than revealed faces would have. Facebook states in its Name Policy, “Facebook is a community where people use their real identities.” Facebook claims to be about real people, real information; no wasted time, no bullshit. Their definition of “your real name” is “as it would be listed on your credit card, driver’s license or student ID.” Imagine if Facebook required your actual face to be used as your profile picture. The portrait you’d upload would be run through a face-recognition algorithm and checked with your state’s driver-license database.

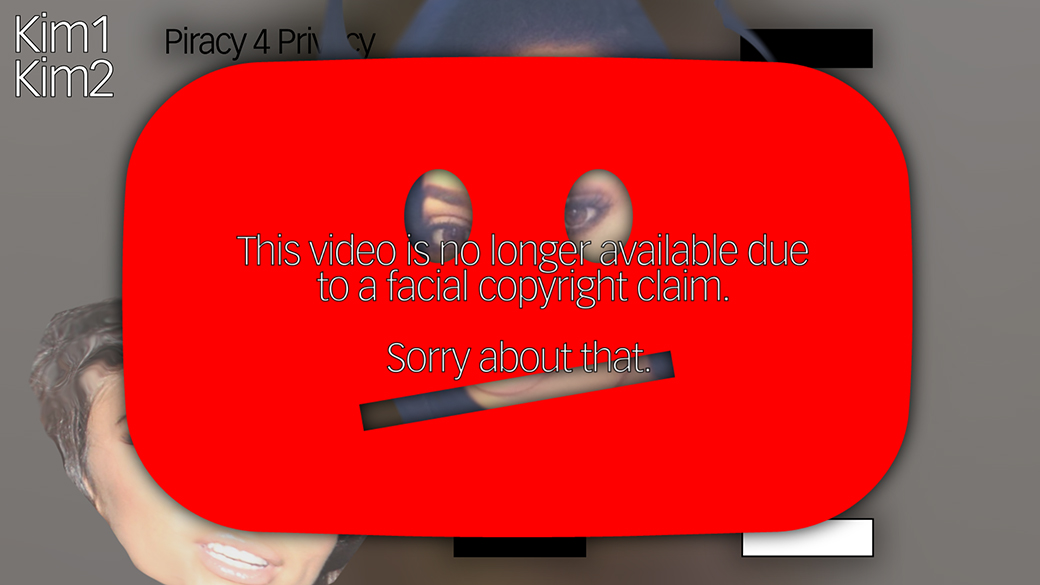

The White House released a document, “National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace,” from April 2011 in which they outline a strategy to enhance online choice, efficiency, security, and privacy by issuing unique online identification codes similar to Social Security numbers. That would be horrifying: forced identification in the name of safety, as well as the limitation to one account per identity. Google’s efforts in unifying each user’s identity across a growing portfolio of products have becoming increasingly aggressive. On YouTube it started with a pop-up window, asking if you want to use your real name or to skip the step. The prompt would vanish for some time, only to return more persistently; now it’s present each time you log into YouTube. It is gracious enough to let me use my old username and account; all this enables, however, is surface-level anonymity. Current privacy policies render other users, not the service or platform, as the threat.

Simone C. Niquille. Realface Glamoflage, 2014. Online store; dimensions variable. © Simone C. Niquille.

BV: In the future of social media, how will ideas of identity and celebrity shift or change?

SCN: Social media made possible self-broadcasting and the creation and cultivation of an image accessible to a broad audience. Traditional media serves as a filter to those in control. My Glamouflage shirt series is based on two types of celebrity. One is the pop star, the politician, or the public figure; those shirts feature celebrity impersonators, never the faces of the actual celebrities. The other is a celebrity through circulation and spreading. The PopUp Girl 1 & 2 shirts were both inspired by the avatars of fake Facebook users from pop-up chat windows. I was curious who the girls were in the profile pictures and how they ended up there. With reverse image search, I found their faces in multiple forums, comments, and social-media profiles, all with different names. Some were obviously fake, others more deceiving. PopUp Girl 1 & 2’s celebrity is caused by existing in multiples—in a way, a privacy through piracy. Traditional camouflage is an attempt to hide in plain sight.

Glamouflage is an experiment in glamorous dazzle, a confusion of facial-recognition algorithms instead of a non-recognition. Glamour suggests something enchanting, magic, or mysterious. In Philip K. Dick’s novel, A Scanner Darkly, the protagonist hides his identity by blending in among others, taking on various human appearances and social identities and ultimately losing himself. In the spirit of PopUp Girl, I imagine a scenario in which taking on different identities doesn’t lead to a loss of self but to a gain, a multiplication into a manifold encrypted identity. I am less interested in the technical feasibility of such a future than in the cultural shift these developments necessitate, one that is arguably long overdue. We need a more fluid understanding of what a corporeal (visual) identity might look like, breaking with our obsession to define, analyze, and categorize ourselves and others.

Pingback: The Future of Social Media: An Interview with Simone C. Niquille | ART21 Magazine | Polly Dory