Ask most photographers how they feel about digital photobooks, and you will likely hear a snicker or see a dismissive scowl. Digital publishing is often identified with glorified PDFs—unsatisfactory facsimiles of what already exists in printed form. The relationship between digital publishing and photography is still an uneasy courtship, with the first recognized digital photobook produced in 2011 (Christopher Anderson’s Capitolio is widely accepted as the first photographic monograph adapted to the iPad and iPhone). These endeavors are variably termed—eBook, iBook, app, digital format project, illustrated digital publishing—indicating the still undefined scope and boundaries of this medium. Photographers and publishers alike appear reluctant to invest in these publishing forms while the results and payoff remain dubious, despite their promise of exciting, unexplored terrain. This reluctance is reinforced by the increasing fetish for printed books and a deeply rooted refusal to accept screen-based fine-art photography; print reigns supreme. And yet there are sound examples that hint at this medium’s potential, instances where the digital form not only is thought provoking in its execution but also is conceptually integrated.

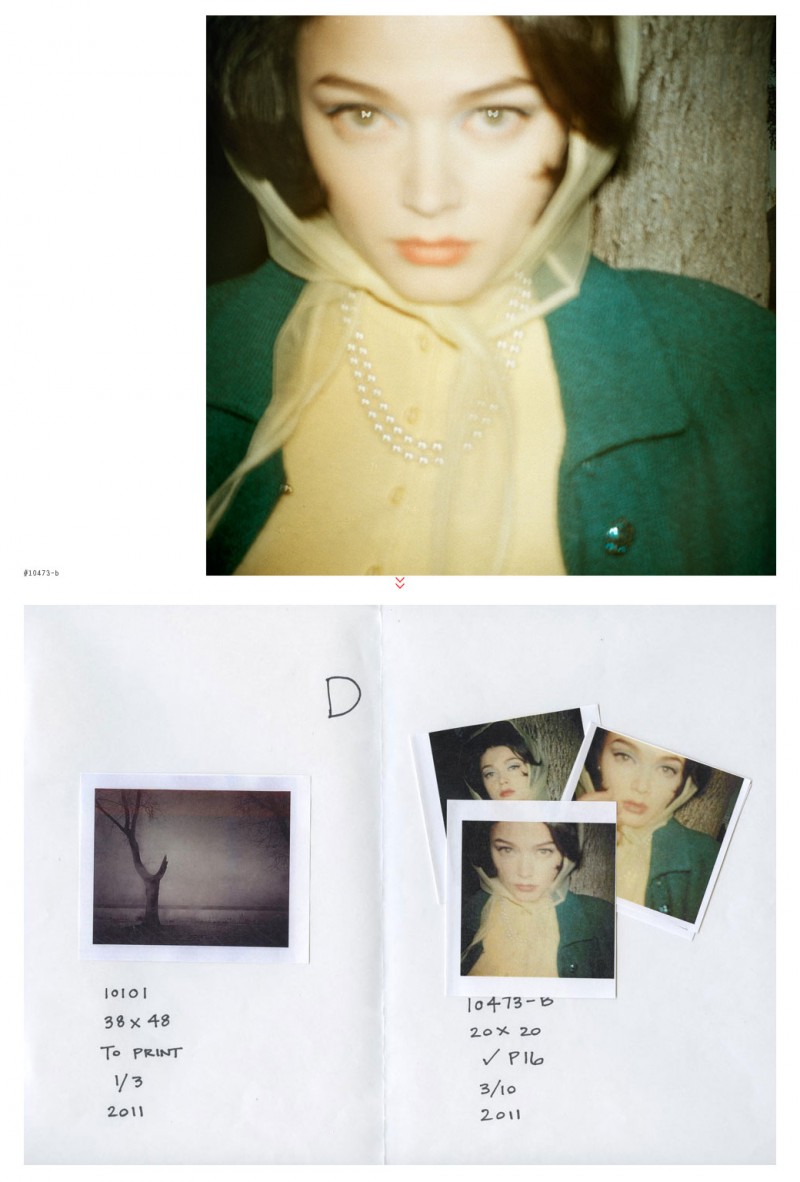

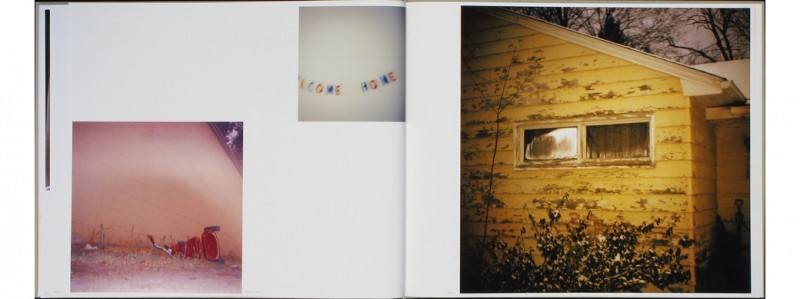

Todd Hido. Excerpts from Silver Meadows. Portland, OR: Nazraeli Press, 2013. Courtesy of photo-eye. © Todd Hido.

The photographer Todd Hido’s forthcoming digital publication of Excerpts from Silver Meadows presents one convincing model. The digital Excerpts embraces its printed counterpart, an exquisite volume published by Nazraeli Press in 2013; the first screens one encounters follow the book’s layout. Long scrolling images approximate the experience of the book’s spectacular gatefolds. Hido collaborated with his longtime book designer, Bob Aufuldish, on this digital project. Aufuldish explains, “We were trying to expand on the experience of the book (not replicate it), and all the design and content decisions were made based on that consideration.” In short, content must dictate form. The screen and other digital aspects should clearly serve the work, as if they are interdependent.

In contrast to the printed book’s concrete, linear experience, the digital version of Hido’s Excerpts employs dynamic navigation and the integration of new content to provide a unique entry point. Where prompted, a vertical swipe directs the viewer to additional content, ranging from project ephemera, exhibition installation shots, and inspirational source material to alternate photographs and videos taken onsite. Hido explains, “I don’t want [the viewers] to be able to change what I did, but I like that they are able to see the choices that I had to make.” These features intimately map his thought process, decisions, and working experience. Moreover, Hido’s combination of content and digital form set a distinctive tone for the viewer’s experience: swipe too quickly and something will be missed. For instance, all of the videos and slideshows initially appear as still images. Through this design, we are not only prompted to take a longer look at each image—antithetical to the widespread, mindless web surfing of today—but also become more acutely aware of the cinematic qualities of Hido’s photographs and the narrative he has spun in Excerpts.

Although Hido’s digital book directly links to a printed book, digital projects of the future are also likely to develop more independently. Already, projects like Jason Evans’s NYLPT seem a far cry from the printed book. In Evans’s project, random sequences of his street photographs are paired with a soundtrack, also randomly generated by seventeen synthesizers. The experience more closely resembles a film than any book, even this project’s book. Stephen Shore has gone a step further with A New York Minute, an exclusively digital project composed of sixteen videos. These three examples from respected, established photographers suggest the wide spectrum of projects conceivable with digital technology and a flexibility that should encourage innovation and experimentation.

Just as the art world in the twentieth century was initially skeptical of color photography, it is unreasonable to assume that digital publishing should be a staple in the photographer’s arsenal four years after its introduction. But the rising generation of photographers, being veterans of the screen, has a different relationship to digital media. As the publisher Michael Mack astutely acknowledged, these photographers primarily use screens to view their work, from the backs of their cameras through to their laptops (Michael Mack, interviewed by the author via Skype, June 9, 2014). The lingering bias against digital publishing will dissipate with time, as photographers, publishers, and designers increasingly explore the depths of this technology. Projects will then earn respect for their distinct merits, shedding the reputation of spurned stepchild to the printed photobook.