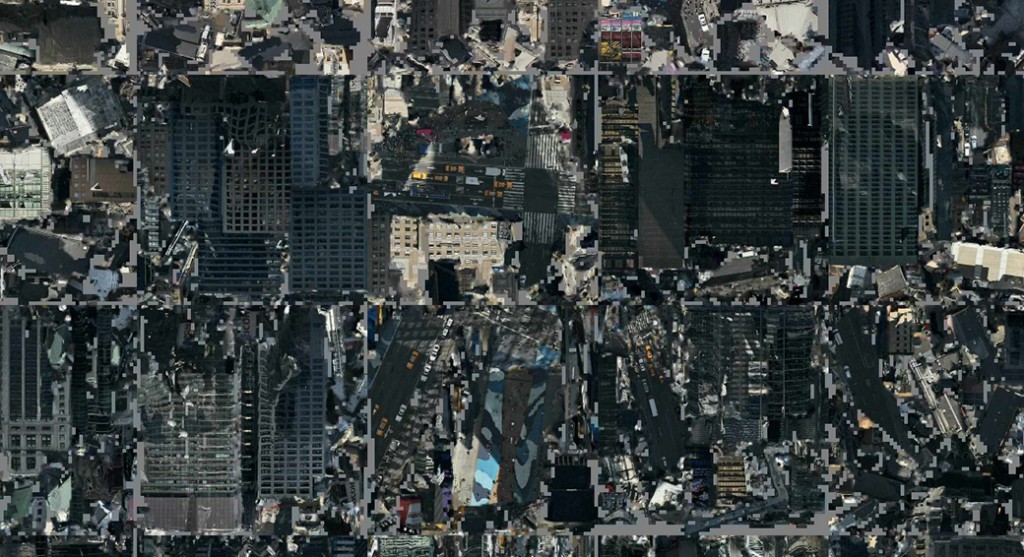

Clement Valla. The Universal Texture, 2012. Inkjet on canvas; 44 x 92 inches. Courtesy the artist.

For thousands of years we have sought to map our world. In the 1670s, Giovanni Domenico Cassini began what became the first accurate, countrywide topographical map of France. The process took over a hundred years to complete; the map had to be finished by his children and later his grandchildren. As our technology has grown more precise, faster, and scalable, so have our maps, becoming globally comprehensive.

Clement Valla, a Brooklyn-based new media artist and Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) professor, explores the underlying processes that produce contemporary maps. Valla focuses on our maps’ fringe conditions, the edges where their perfect sheen frays. While intellectually we understand that our maps are always only representations of the world, sometimes we forget that. Via email, I conversed with Valla to get his perspective on these maps.

Ben Valentine: In “No to NoUI,” Timo Arnall wrote:

“Invisible design propagates the myth of immateriality. We already have plenty of thinking that celebrates the invisibility and seamlessness of technology. We are overloaded with childish mythologies like ‘the cloud’; a soft, fuzzy metaphor for enormous infrastructural projects of undersea cables and power-hungry data farms. This mythology can be harmful and is often just plain wrong. Networks go down, hard disks fail, sensors fail to sense, processors overheat and batteries die.” (Timo Arnall, “No to NoUI,” Timo Arnall, March 13, 2013.)

As these mapping technologies become more comprehensive and precise, windows into their inner workings like those that you have documented will disappear, leaving us with a false impression of a comprehensive, seamless, and perfect map. What are the embedded politics of a map such as this?

Clement Valla: I’ll start with the first part of that question. I’m not so sure the ruptures or windows into the inner workings of mapping technologies will ever disappear. Rather, the representations of these maps will start looking more ordinary. For example, the current trend is for maps to look more like photography, using 3-D, perspectival points of view. So we have developed a kind of habitual, unquestioning response to them because we are so conditioned to a particular way of looking at photographs.

Or perhaps the maps will evolve into some new form of representation, new images, that we will also become habituated to. The key thing is that in their everyday use, the representations become habitual and ordinary. But then there will always be a way to take this completely ordinary, plain thing and reveal its biases, its brittleness, and the particularities of its representation and mediation.

Getting back to your question: the politics of such a map is as old as mapping itself but with some new particularities. Maps have always been representations of space produced by entities with financial or political power. These representations become problematic when they take on the air of objective truth through use and habit. A common example is how strange it is to look at a south-up map. So the map or territory issue here is pretty well staked out.

What aggravates the problem in this era is automated symbolic manipulation by algorithmic entities. In other words, the apparatus producing the map is automated to such a degree that it becomes easier to believe it is truthful. It is harder to spot the biases and easier for us to imagine that algorithms deal with the data objectively. So the work of understanding the gap between the map and the territory becomes the work of understanding the biases in the algorithms, the sensors, and the mechanics of the map-making apparatus as a whole.

BV: In “The Universal Texture” you write,

“Nothing draws more attention to the temporality of these images than the simple observation that the clouds are disappearing from Google Earth. After all, clouds obscure the surface of the planet so photos with no clouds are privileged. The Universal Texture and its attendant database algorithms are trained on a few basic qualitative traits—no clouds, high contrast, shallow depth, daylight photos.” (Clement Valla, “The Universal Texture,” Rhizome, July 31, 2012.)

What do you see as the endgame here? What else will be erased from our maps?

CV: Wow, great question, but I really have no idea. This comes down to what is deemed useful to those building the apparatus. In my essay I tried to make the maps sound like the equivalent of shopping malls and contemporary airports: spaces that are always on, full of sedate spectacle, cheap and glossy, and perfect for pushing consumption—basically the kind of space described by Rem Koolhaas in his essay “Junkspace.”

So as the maps evolve, and data collection and advertisements evolve, the designers of these systems will gravitate towards elements that are the most monetizable and try to edit out elements that cause any sort of friction in the use-data-mining-advertisement cycle. What will keep users mildly entertained enough to keep contributing? What functions will be useful enough to keep users clicking? What will divert attention away from the maps?

Pushing the mall/airport analogy, I’m assuming the maps will tend towards the colorful antiseptic: just enough flavor to seem wonderful but no real representation of poverty, war, ecological catastrophe, inequality, or anything no one wants to talk about while shopping for the perfect screen-cleaning solution or trying to get from highly ranked point A to highly starred point B.

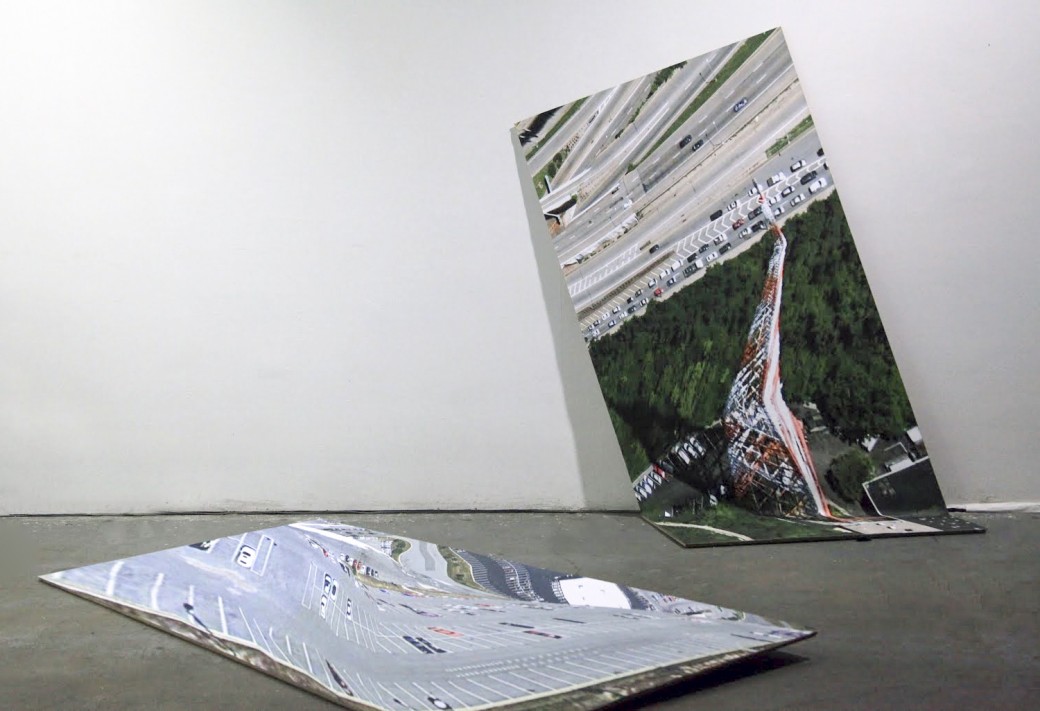

Clement Valla. Postcards from Google Earth, 2010. Website and postcards. Courtesy the artist.

BV: Your 2010 series Postcards from Google Earth, the 2012 essay “The Universal Texture,” and your 2013 project 3D-Maps-Minus-3D all bring to the fore the hidden systems and limitations of these new mapping technologies. As these technologies rapidly advance and the limitations you have documented are programmed away, what level of detail and capabilities do you envision these mapping programs will possess in our lifetime?

CV: That’s a tough question as I don’t think I’m so good at speculating on the future. The one place I see much of this going is the increasing integration of geographic data, and geo-location functions within the other services of these tech companies, like self-driving cars, mobile platforms, invasive eyewear, and so on. The financial incentive for all this will probably still be based on advertising and monetizing our attention, using the very data we generate while using these services—so, kind of, an infernal loop. Geographic data is just another part of the metadata that we will generate for free to get to use some nifty new techno-thingy, and that will be aggregated, mined, and sold.

My sense is that the big mapping battle between Nokia, Google, Apple, and Microsoft has a lot to do with owning the infrastructure that will collect the most metadata from our devices and cars. I could be wrong, but I almost think the self-driving car is the logical solution to the Streetview car problem: How do we get more Streetview cars? How do we update the map more frequently? How do we know where everyone is on the map? Well, why don’t we stick everyone in a Google car?

Clement Valla. 3D-Maps-Minus-3D, 2013. Website. Courtesy the artist.

BV: Do you see open source mapping projects like Open Street Map becoming more robust and used? What role will they play in the future?

CV: I am actually quite pessimistic about this one. I am excited by the tools and the development of open-source mapping projects, but I think there’s an imbalance in terms of access to data. Google Glass, i-Phones, self-driving cars—all of these devices will eventually be used as data-gathering points to feed the maps of the corporate giants. Until people realize their data has actual value and are unwilling to give it up for so-called free services but rather direct their data consciously and politically, it will be increasingly hard for open-source projects that rely on large data sets to compete. Furthermore, the only options seem to be either corporate or open-source, whereas traditional big data and mapping had been the province of governments. Open-source tools could work out extremely well using open, taxpayer-funded, government-produced data. But the scales seem to be tipping in favor of privatized, ad-funded data instead.