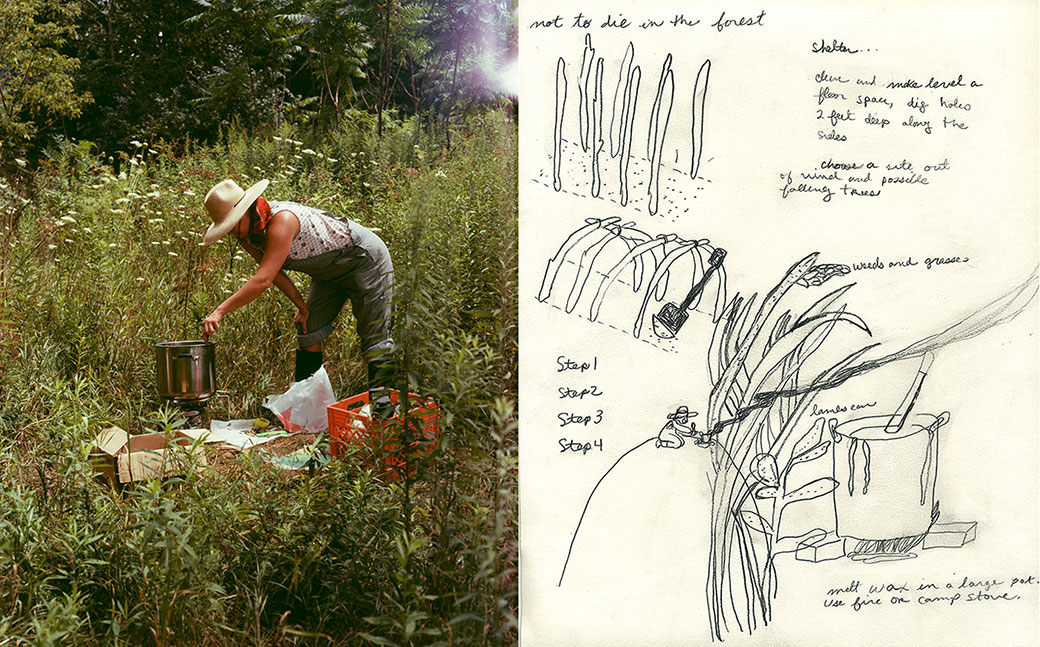

Left: Heidi pouring wax on Cobra Lilly Mountain. Archival pigment print, 2011. Photo: Eileen Mueller. Right: One of Heidi Norton’s drawings from the artist’s book Art in the Earth: A Field Guide from the Soil to the Studio, a collaboration with Monica Westin, 2012.

In the United States, homesteading has historically been linked to revolutionary impulses and radical social initiatives. For good and for ill, the country was founded by homesteaders, who settled on—or, more aptly, occupied—what were originally Native American lands. The twentieth century saw the largest urban-to-rural migration in our country’s history: the back-to-the-land movement of the 1960s and ’70s, in which countless Americans, many of them still in their early twenties, ditched their lives in the city in search of living in greater harmony with nature.

The word revolution in this case refers to the cyclical nature of history and of social and cultural trends. Today, many aspects of the movement have returned to popular practice, albeit in atomized form: urban and suburban backyard chicken coops and bee hives, edible front yards, small or tiny houses, home canning and soap- and candle-making, and the dozens of blogs and websites that enable aspiring homesteaders to gather together—this time, in online virtual communities—to share knowledge, experiences, and sustainable living strategies. Can we still think of these new forms of homesteading as radical, much less revolutionary?

Heidi Norton. Trading Post, 2014. Installation view: Elmhurst Art Museum. Mixed media; dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist.

The work of the artist Heidi Norton reflects on these and other related questions. Her complexly layered photographs and sculptures, on which she often affixes organic materials such as plants, earth, and other living or once-living matter, are rooted in her early memories of living intimately with the land. Her parents, John and Sheila Norton, were back-to-the-land homesteaders in West Virginia forty years ago. I talked to the artist, her parents, and her cousin Ryan Couto (who is currently building a tiny house) about the social, political, cultural, and aesthetic aspects of homesteading, then and now. Our intergenerational conversation looked at the ways that memory and landscape account for a widespread desire among Americans to “go back” to the land—to a sense of place from which they’ve grown far removed—and how the loss of a very particular, intimate relationship to a landscape shapes the artist’s research-based approach to making art.

Claudine Ise: John and Sheila, what prompted your decision to go off the grid when you were twenty-two and eighteen, respectively? How did you live, eat, and travel?

Sheila Norton: We both were disenchanted by the Vietnam War and were afraid of nuclear power. We also loved nature. In 1973 we left Baltimore and moved to a remote property in Lincoln County in southern West Virginia. There, we lived on thirty acres for a year and a half. We didn’t have a car; we hitchhiked or walked everywhere.

Johnny and Sheila’s communal gathering at their wedding in 1975. Courtesy Heidi Norton.

We constructed a three-sided lean-to that served as our shelter. Friends helped us cut down and strip trees, and we traded labor to a neighbor in exchange for him and his team of horses pulling the logs to the site. Electricity wasn’t necessary. We used hand tools to fell the trees and strip the bark, and we cooked on an open wood fire. I baked using a solar oven that John constructed. We ground acorns for flour; we dug a hole in the ground inside the lean-to and sealed it to keep our food cool.

After a year and a half, we moved to the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia, about an hour and a half from Baltimore and Washington, DC. We lived on ten acres in a small area that bordered a quarry. There, we started a food co-op that still exists today.

CI: Heidi, in 2012 you did a residency at Artists’ Cooperative Residency and Exhibitions (ACRE) where you set up a studio in the woods. Did you think of your studio in the woods as a type of homestead?

HN: A studio can be wherever you make it. Its goal is production. Products are created based on [the artist’s] skills and the resources around them. I was thinking about craftspeople and artisans versus Artists (with a capital a). The back-to-the-land movement attracted disenfranchised but educated dropouts (many had only minimal handcrafting and building skills); countless of them moved to the Appalachian Mountains. There, they encountered locals who had been homesteading and making handcrafted products since the land was first settled in the late 1700s: baskets, pots, furniture, textiles. These people were making to survive. This element of crafting based on the terms afforded by the land interested me. My studio in the woods was about performing and creating in a space where I as the human must negotiate with a natural world and those terms would dictate what I produce. Everything around me—the sun, the bugs, the animals, the weeds—informed where, how, and what I made.

CI: Talk about the camera obscura you and your cousin Ryan designed and fabricated for your 2014 Elmhurst Art Museum solo show.

Heidi Norton and Ryan Couto. Camera Obscura, 2014. Installation view: Elmhurst Art Museum. Reclaimed palette wood, corrugated metal, submarine portal window. Courtesy the artists.

HN: A camera obscura’s function is to take light and focus it into an image. It’s a moving image of real time, inverted. It takes invisible light waves and makes them perceptible. Similar to what a photograph does for a memory—it legitimates it. Looking at the projection feels similar to watching a moving photograph of the surrounding area. You see trees blowing, clouds moving, kids playing. The inversion of the image summons thoughts of lying on the ground, feeling the cold earth on your body, watching the trees sway back and forth, the clouds forming creatures. It evokes sentiment and maybe even nostalgia.

CI: Yes, but the difference, as you pointed out, is that with an image you can’t actually feel the earth against your back—you only recall or imagine the sensation. We experience nature as an inverted image, displaced from its real, material context.

Ryan, you’re building a tiny house right now that you’ll affix to a trailer, so you can travel around the country in it. Will you speak about this idea of displacement?

HN: When traveling in the tiny house and trailer, Ryan’s relationship to the land will be in a constant state of de-contextualization.

CI: And constant re-contextualization, too.

Ryan Couto and his brother James Couto’s Tiny House in progress, started in 2013. Courtesy the artists.

Ryan Couto: My experience with this idea of decontextualizing comes from road trips around the country, setting up camp, exploring the area and then moving on after a few days. By being placed in different remote locations, our house will have an ever-changing backdrop. The building plan was just within our skills and cheap enough that we knew we could pull it off. We are using a lot of salvaged building materials that served previous lives in conventional homes. Even our trailer frame was once a more traditional-looking nineteen-foot travel trailer.

CI: John and Sheila, what do you think of the urban homesteading practices that are becoming more widespread today?

John Norton: It’s interesting—mostly vegetable gardening and chickens, living in close proximity to others without offending anyone. I’d like to see the concept expand to a neighborhood thing, with everybody growing something and then having a Sunday potluck and garden exchange with crafts and bartering.

CI: Speaking of bartering: Heidi, your recent exhibition at the Elmhurst Art Museum included a trading post where you invited visitors to take something and leave something. How did that work?

HN: The trading post was originally meant to be a place where people of all ages could commune and exchange and swap stories, tips, and knowledge. It was also about an interchange between artist and viewer, redefining their roles through the act of trading. However, the museum context and the parameters surrounding the solitary act of viewing left the trader without opportunities for face-to-face exchanges—only a space where goods were offered. The trader goes through a series of self-negotiations: “What do I have on me? What do I carry? Is my possession worth that object posing as art?”

The trading post turned out to be more of an offering place, where visitors took pleasure in leaving parts of themselves behind, regardless of what it was—a souvenir marking their own presence within the exhibition, a sign that “I was here.” That part I enjoyed.