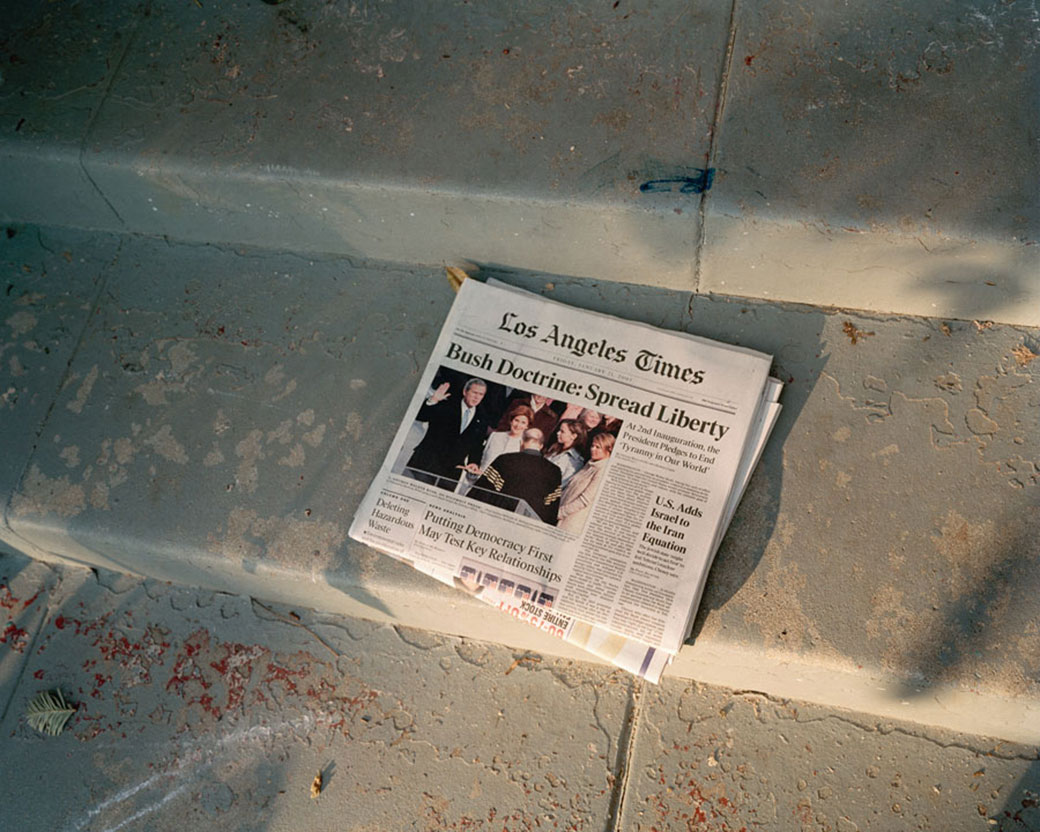

Catherine Opie. Friday, January 21, 2005, 2005. From the series In and Around Home. C-print; 16 x 20 inches. Edition of 5, 2 AP. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Catherine Opie

Catherine Opie investigates the ways in which photographs both document and give voice to social phenomena in America today, registering people’s attitudes and relationships to themselves and others, and the ways in which they occupy the landscape. In this excerpt from a newly published ART21 interview, conducted in 2011 at Opie’s Los Angeles studio, she discusses concepts of utopia and dystopia, her personal style of documentary photography, and the idea of America as the great democracy.

ART21: You come from a part of the country that had utopian colonies. How do notions of utopia impact and maybe reflect out of your work? And how might you talk about this to someone who wouldn’t have connected utopian thinking to your work?

Catherine Opie. Untitled #2 (Boy Scout Jamboree), 2010. Inkjet print; 18 x 24 inches. Edition of 5, 2 AP. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Catherine Opie

OPIE: I am really interested in utopia and also the dystopic. I’ve read a lot of sci-fi novels that play with those ideas, and I’m a huge Octavia Butler fan. I’m interested in how she constructs ideas—not only of sexuality, but also what is utopic and dystopic. In a way, it’s the same kind of binary as normal and abnormal. Supposedly we construct those binaries to be able to create a model to live by. My utopic notion is humanity: I’m utterly devoted and dedicated to being a humanitarian and trying to live my life in a way in which both my work and myself allow a kind of representation that creates kindness and a way to observe the world in relationship to how I think about it and view it.

I have a hard time with mean photographs. There is already so much meanness and discouragement in this world. I’m not sure what it means to create representations of people that show them in their worst light. So I believe in creating representations that are sometimes tough but, at the same time, the core of humanitarian ideas exists within that. Even though there are some tough ideas in the work, it’s still done in such a way that’s not meant to ever be disturbing. So, my perfect world (which I’ll never see because I don’t believe that it exists) is about acts of kindness. It’s about the fact that we have the ability not to have people starve. We have the ability not to go into war over religious ideology. We could become a sustainable country; we could stop global warming if we chose to. We choose not to. And that’s the dystopic nature of us as humans. I could represent that, but I’m not interested in representing that. That’s my everyday; that’s the front-page newspaper. That’s the Channel 4 News that I’m interested in creating a dialogue with in relationship to my time and what I observe. But I’m not interested in trying to make images that reflect what is so prevailing.

Catherine Opie. 30 Minutes After the Inauguration, 2009. From the series Inauguration. C-print; 16 x 20 inches. Edition of 25, 5 AP. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Catherine Opie

ART21: Are there were one or two bodies of work within your exhibition Empty and Full at the ICA Boston that you want to concentrate on in this conversation?

OPIE: I think Inauguration is interesting to talk about. Describing that event photographically compared to what the media was showing also hinges on ideas of utopia and dystopia. I decided that I wanted to create a portrait of our time in America, in relationship to the incredible opposition discourse. What I’m interested in is the notion of America being the great democracy (and I’m not sure that it’s the great democracy). Within this notion there are always binaries—normal-abnormal, utopic-dystopic, Republican-Democratic. I really wanted to make American landscapes in terms of identity—through Tea Party rallies, the Inauguration, Boy Scout jamborees, the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, immigration marches. I became really aware of people taking space—exercising their freedom of speech. I was more interested in the way they occupied landscape, whether or not I believed what was being spoken.

Catherine Opie. Untitled #2 (Tea Party Rally), 2010. Inkjet print; 16 x 24 inches. Edition of 5, 2 AP. Courtesy of Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Catherine Opie

All of these things are always coming up in relation to the nightly news, and I’m fascinated with it as a construct. I love the nightly news; I have watched it since I was a kid. And that’s probably because I was born in ’61, and the nightly news was the constant of information: Vietnam and the civil rights movement. Those were the images that profoundly affected me—that formed me as a person—like the images of the Renaissance and paintings that I saw as a child in the art museums. And that’s also probably, going deeper, the relationship to the notion of document or documentary in my work.

Catherine Opie. In Protest to Sex Offenders, 2005. From the series In and Around Home. C-print; 16 x 20 inches. Edition of 5, 2 AP. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles. © Catherine Opie

Right after 9/11 or when I had finished Wall Street (2001), I was looking at exhibitions around Chelsea, and there was just one flower exhibition after another. The way that photography was radically changing within the art world was frustrating for me. If you made work that had street-photography language within it, you were thought of as a photojournalist, and “documentary” as a language started getting wiped out. I was like, “Why aren’t people observing anymore? What’s wrong with this kind of observation?” I was compelled to pick up a camera and start photographing. I think it started with In and Around Home (2004–05), and I ended up photographing crowds of people. There are photographs in that body of work that are really important to me, that signified this shift of wanting to begin to photograph larger groups… I was back on the street with a camera in my hand, like I was in the early ’80s in San Francisco. I was looking at groups of people that had come together, and I realized that it was really important for me to no longer empty out the landscape, but to fulfill this other notion of creating documents of our time, in relationship to going out and observing—creating another way of looking at American landscape.

Read the complete transcript, “Catherine Opie: Shifting Observations,” at art21.org.