Cameron. West Angel, n.d. Graphite, ink, and gold paint on paper; 23 3/4 x 36 3/4 inches. Courtesy the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and the Cameron Parsons Foundation, Santa Monica. Photo: Alan Shaffer.

The imminent possibility of magic seems to perennially hover over Southern California, an area long known for its experiments in alternative spirituality and its visionary optimism. Gurus, healers, psychics, and witches are common in Los Angeles, and their worlds often intersect with the world of artists; after all, both are engaged in probing the boundaries of life as we know it.

In October 2014, a retrospective of the work of Cameron (1922–95), an influential counterculture artist and practicing witch, opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Pacific Design Center, generating excitement and substantial media coverage. Not well known outside of Southern California, Cameron has exerted a mythical pull on local artists, occult enthusiasts, and historians for decades. Her drawings and paintings, often depicting fantastical creatures engaged in mysterious rituals, are suffused with an otherworldly energy while her appearances in underground films such as Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) reveal her personal charisma—still potent even now, years after her death.

The idea that magic is possible is always a seductive one, and many are no doubt drawn to Cameron because of the legends that surround her. As the story goes, the rocket scientist and occult practitioner Jack Parsons, who became Cameron’s husband, believed that she was the elemental—the spiritual energy in human form—that he had summoned through a ritual invocation performed with his friend and fellow spiritualist, L. Ron Hubbard. Called the Babalon Working, this spell was one of the few Parsons performed that, he believed, had actually worked.1

Today, younger artists in Los Angeles are continuing to engage with alternative forms of spirituality. Rather than perpetuating a certain mythos, however, some of them are appropriating occult tools within a larger progressive agenda. Two artists, Maya Gurantz and Amanda Yates Garcia, utilize rituals and spells in ways that are socio-politically inquisitive and, ultimately, activist.

In the short video Magick (2011), Maya Gurantz enacts a version of a “sex magick ritual” alleged to have been performed on Jack Parsons’s lawn during his notoriously debauched house parties, in which “naked pregnant women leap[ed] through fire circles.”2 Gurantz read the description of this event while she was pregnant and decided to perform it, with herself as the nine-months-pregnant protagonist.

Although the video has a strong mystical ambience, it is also inflected with humor, as a very pregnant Gurantz thunders around the stage and leaps through the circles of fire three times before coming to a rest. It is also significant that Gurantz is the one who owns the ritual, initiating it and occupying its central space with her body, rather than acting as an ornament or totem. Magick is actually part of Little Thefts, a larger series that “interrogates the fantasy of the Male Genius, to both undermine and, as a female artist, to occupy it.”3 Gurantz aims to expose the anxieties inherent to this fantasy, anxieties that she is “both biologically excluded from, but also inevitably shaped by.”4

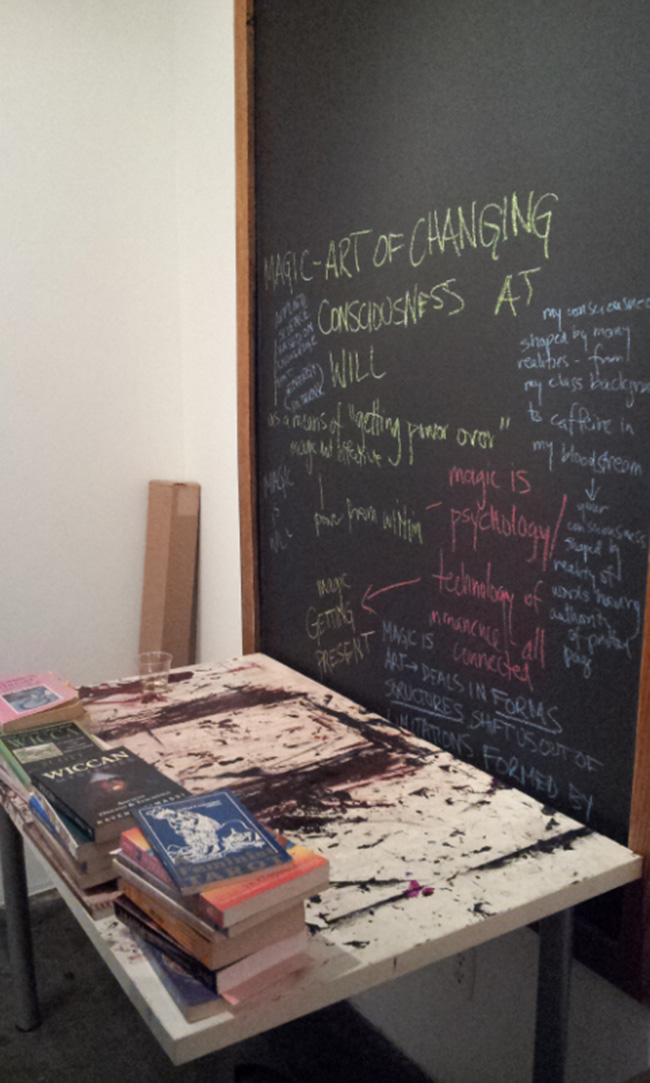

Evidence of Maya Gurantz’s research during her residency at the Institute for Cultural Inquiry, Summer 2014. Photo: Carol Cheh.

A self-proclaimed skeptic, Gurantz hails from a family of atheists and scientists and does not consider herself a follower of the occult. Rather, her work—which incorporates movement, performance, and text—engages in a larger anthropological study and critique of the power dynamics inherent in social and cultural structures. This inquiry sometimes takes her into the realm of the occult, which has historically been a hotbed of hidden anxieties as well as improvised solutions to social problems.

During a recent residency at the Institute for Cultural Inquiry, Gurantz immersed herself in a study of feminist spiritualist texts, delving into the history of magical practices, which often responded to or explained common domestic problems. She mused at length on the nature of magic itself. Reflecting in her blog on her findings, Gurantz wrote: “Because women had no real power, no real choices, they are left with magical solutions or divine punishment or divine threat…Women’s tools are mostly symbolic. And often, communicated with narrative…Perhaps still, magic is all we have.”5 To commemorate the end of her residency, Gurantz invented a participatory autumn ritual to herald the changing of the season.

Amanda Yates Garcia, also known as the Oracle of Los Angeles, practices paganism and various forms of magic and spirituality. She initially inherited the craft from her mother—who abandoned her Unitarian background in favor of Wicca when Garcia was a child—but eventually wed it with an artistic and literary practice to create something new and entirely her own.

Amanda Yates Garcia (the Oracle of Los Angeles). Solidarity Spell, conducted October 12, 2014 at Human Resources, Los Angeles. Photo: Susan Li.

Although Gurantz and Garcia come to spirituality from opposite ends of the belief spectrum, they do have key aspects in common, one being a youth informed by anger at social injustice. Both recall railing as young women against patriarchal oppression, sexism, environmental destruction, and economic inequity; both eventually developed a practice as a means of constructively channeling frustration. Whereas Gurantz chose a path that straddles scholarly study, visual art, and performance-based explorations, Garcia’s path is one that blends magical practice, creative production, and empowerment of herself and others.

As a child growing up in Goleta, California, Garcia found her suburban surroundings to be devoid of magic and beauty. The prosaic strip malls and incessant traffic contrasted sharply with her lively home life, in which she was frequently visited by fairies and spirits while her mother taught her magic and tarot. Similarly, when she entered the art world, she was dismayed by how the commercial demands of the marketplace often tamped down artists’ creative energies and visions. Garcia sees “both magic and art as means of transforming our perception of reality”; she believes that her job as an artist is to “re-invoke magic and point out the ways that magic is already here and present in all of our lives.”6

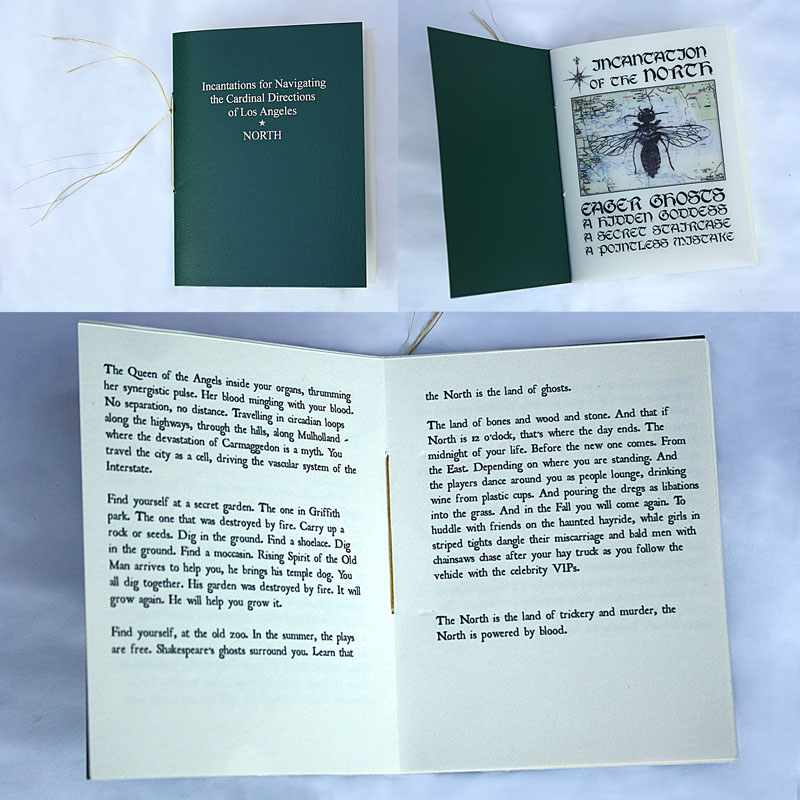

Amanda Yates Garcia. Incantations for Navigating the Cardinal Directions of Los Angeles, 2013. Courtesy the artist.

In a self-published set of books called Incantations for Navigating the Cardinal Directions of Los Angeles (2013), Garcia helps readers to navigate the northern, southern, eastern, and western reaches of the greater Los Angeles area. Something between whimsical guidebook, fractured narrative, stream-of-consciousness poetry, and affirmative meditation, this set of four small chapbooks seems to travel on a road of buoyant words through the many rambling scenarios of the city. The book of the north begins with this directive:

You will seek to find the true spirit of the North

You will ascend the secret staircase

You will find purpose and strength

You will take The 5 North

Your strength will grow tenfold

Your power will grow by the power of The 10

And you will achieve your heart’s desire

In the book of the east—whose thickness reflects the high concentration of artists living and making projects on the eastern side of the city—a variety of funky narratives with shifting protagonists leads the reader on episodic adventures in Chinatown, Highland Park, Mount Washington, Pasadena, and points further east. The speaker/reader walks her dog, attends an art opening, thinks about his next book, quits her office job, contemplates a moonrise, kills Hitler as a child, and is born again. The book ends with an exhortation: “You are the spirit of nature / a living earthly thing. / Rise up!” By effortlessly juxtaposing everyday chores and actions with magical visions and affirmations, Garcia’s highly engaging texts seem to re-enchant daily life and open possibilities for transformation.

As the Oracle of Los Angeles, Garcia makes herself available for consultations and for performing rituals and spells. At a recent organizing event for art-school adjunct faculty, who have faced increasing job insecurity and wage inequality in recent years, Garcia performed a solidarity spell to unite the room and encourage participants to think as a whole. With everyone in a circle holding hands, Garcia led the faculty members in a series of howls directed at a bowl of water in the center of the room, charging it with the energy of solidarity. She then encouraged people to bless each other with the water throughout the rest of the evening, which many did.7

In a contemporary world that is as pragmatic as it is visionary, magic—as practiced by these two artists—is not so much an ineffable phenomenon as it is a tool for change. As Garcia says, “The magic works because we say it works. As we say it, it happens—it’s really about transforming consciousness, and through that, the material world as well.”8

1. Yael Lipschutz, Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman (Santa Monica: Cameron Parsons Foundation, 2014), 9.

2. Mike Davis, City of Quartz (New York: Verso, 2006), 59.

3. Maya Gurantz, “Little Thefts,” Maya Gurantz, https://mayagurantz.com/for-my-enemies/ (accessed December 8, 2014).

4. Maya Gurantz, “Little Thefts.”

5. Maya Gurantz, “Feminist Book Report: Les Évangiles des Quenouilles,” Ten Red Hen, https://tenredhen.wordpress.com/2014/07/08/feminist-book-report-les-evangiles-des-quenouilles/, July 8, 2014 (accessed December 8, 2014).

6. Amanda Yates Garcia, KCHUNG Radio interview, https://archive.kchungradio.org/2014-01-19/Performance_Now-01.19.2014.mp3, January 19, 2014 (accessed December 8, 2014).

7. Marco Franco Di Domenico, “Art, Education & Justice!—Art school faculty across Los Angeles are organizing,” Another Righteous Transfer!, https://anotherrighteoustransfer.wordpress.com/2014/10/27/art-education-justice-art-school-faculty-across-los-angeles-are-organizing-by-marco-franco-di-domenico/, October 27, 2014 (accessed December 8, 2014).

8. Amanda Yates Garcia, KCHUNG Radio interview, https://archive.kchungradio.org/2014-01-19/Performance_Now-01.19.2014.mp3, January 19, 2014 (accessed December 8, 2014).