I have a recurring dream. I’m running through the crumbling urban landscape of the South Bronx in the 1970s, the neighborhood where I grew up, and I’m filled with a sharp sense of fear for my corporeal safety. New York City was hard then—we all lived under the constant threat of physical danger. By the early 1980s we were drowning in disinvestment and swimming through the broken glass of the crack epidemic, and the city felt like it was on the brink of collapse.

This fear of physical annihilation lived deep in my bones and tunneled into my psyche, but now it lives only in my dreams. Lately I have instead been experiencing a new type of fear, a cold mist that crawls across my skin and seeps into my spirit. It is a fear of existential ruin, the annihilation not of my body but of my whole kind. It feels like something in my city is being irretrievably broken. Back in the ’80s we could never have imagined that the end would not be an apocalypse of violence but rather a clean erasure, an imperialist takeover: gentrification.

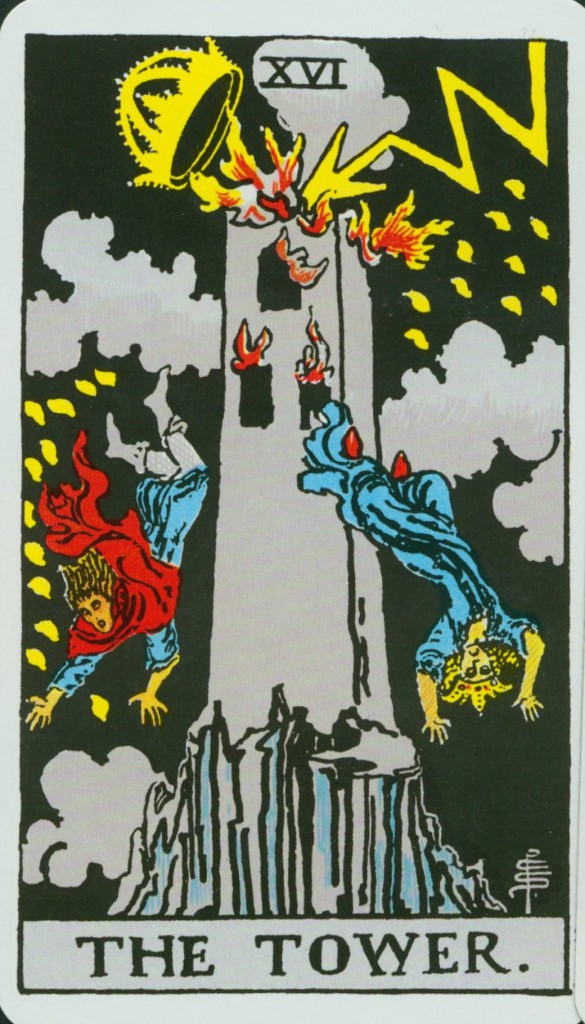

Ruin is the after-death. Architectural edifices become ruins after all use has been leached from the bones of a structure, though the words use and bones and even structure are subjective terms. Who decides what is useful, and what is not? How do we know when something is obsolete, ready to be left behind? How do we use space, and does all space need to be updated? How do we decide which bodies, architectural and animal, are valuable and which are not? Whose structures are we upholding, and whose are we ignoring or actively destroying?

We are rebuilding cities from the outside in and hiding our existential decay under impervious facades, as the warren of rentals becomes a honeycomb of individually owned bits of sky. These “ruins in reverse,” (to use Robert Smithson’s phrase), go up every day in contemporary cities across the globe—behemoths of steel and glass that displace and rearrange and erase what went before. They are like Smithson’s New Monuments: “Instead of causing us to remember the past like the old monuments, the new monuments seem to cause us to forget the future…They are not built for the ages, but rather against the ages.”

In thinking of ruin as a theme for this issue of ART21 Magazine, I was most interested in the non-material aspects of ruin, of the erosion of the social contract as a kind of ruin, and how the erosion of physical infrastructures can be related to a corrupt form of social contract, manifesting in practices like redlining, deliberate racial segregation, gerrymandering, harsh immigration policies, and disinvestment in public resources.

In this Ruin of an issue, we court and adore physical decay for what it can teach us. We question the inexorable slide into prosperity, and we track the contrast between market forces and corporeality. We look for home and ask for mercy. We suggest solutions and promulgate complications.

Ultimately, this Ruin is a celebration of vulnerability—the vulnerability of all matter to decay, the vulnerability of bodies observed and ignored, the vulnerability of social contracts and civic agreements—and a big laugh at the tremendous, precarious nature of the whole teetering system.

Ruin is the after-death. Long live ruin.