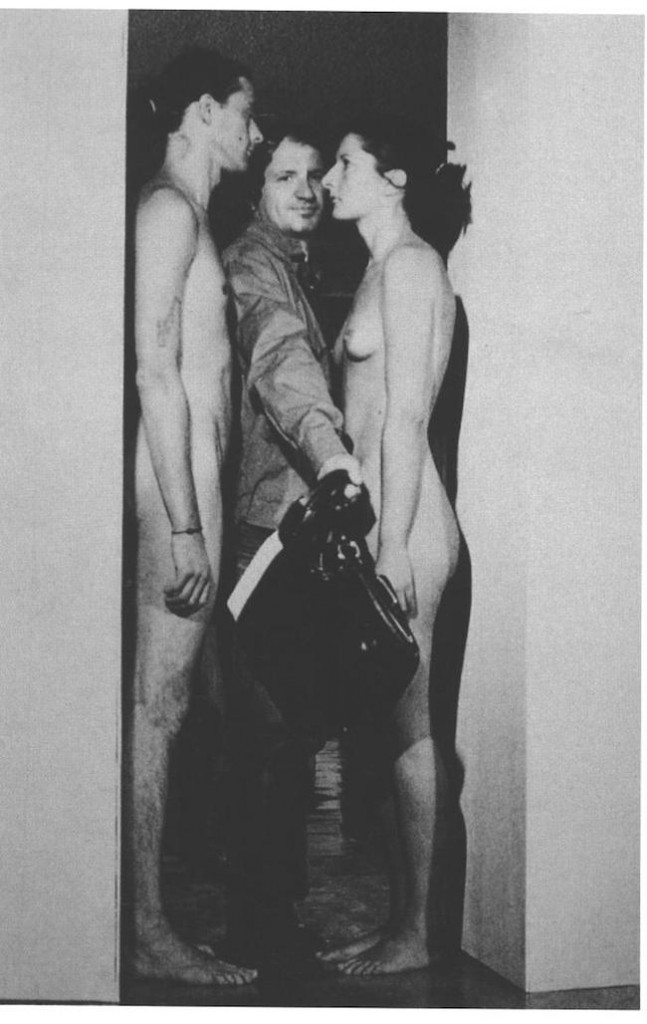

Imponderabilia; exhibition view, Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present, 2010; Museum of Modern Art, New York. Re-performed by Maria S.H.M. (left) and Abigail Levine (right); security guards not pictured. Photo: Scott Rudd.

During the spring of 2010, I spent several hours each day, usually unclothed, either standing, sitting, lying, or perching on a bicycle seat in the sixth-floor galleries of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), reperforming five works in Marina Abramović’s retrospective, The Artist is Present. My most regular assignment was Imponderabilia, a piece in which two naked performers face each other across a doorway. In the work’s first performance in Bologna in 1977, visitors had to pass between the performers, but, as noted by many critics and scholars, significant changes were made to the work at MoMA. The doorway was no longer the entrance to the gallery and was widened, making the passing between the nudes optional rather than mandatory. The most significant shift, from my perspective, was the decision to surround the pair of performers with a pair of security guards.

This new version was a double performance: the passageway between the performers stood within one created by the guards. The postures of the two pairs were nearly identical, though each had a different repertoire of permitted behaviors and a different understanding of their function. Arguably, the guards, interacting directly with nearly every person who passed through the doorway, had as much effect on the viewer’s experience as the performers. Many commentators saw the presence of the guards as constraining the risk that had made the work vital in its first iteration, performed by Abramović and her partner, Ulay. However, in another light, this arrangement served, like the first performance (though surely unwittingly) to make Imponderabilia a reflection of conditions in the art world and the wider society. All the issues raised by passing between the naked, mostly white performers—power and trust, vulnerability chosen and imposed, labor made immaterial and invisible, social contracts and their violation—was refracted in larger terms by passing between the uniformed, mostly African-American and Latino guards.

Imponderabilia; exhibition view, Marina Abramović: The Artist is Present, 2010; Museum of Modern Art, New York. Re-performed by Maria S.H.M. (left) and Abigail Levine (right); security guards not pictured. Photo: Scott Rudd.

I have written about this scene before in relation to questions of labor and performance. At MoMA, the guards and performers were working within parallel conditions of precarious employment. Before the galleries opened, guards spoke about the many challenges of the job and how these resulted in unusually high turnover. The work of the performers didn’t fall neatly into the employment structures of either the performing or visual arts. After receiving an unacceptable initial performance contract, we successfully negotiated to change our status from independent contractors to part-time employees, setting a precedent at MoMA and elsewhere. However, despite our common ground, we did not think to align our employment situation with the work of the security guards or others in the museum with similar situations.

I thought of the MoMA Imponderabilia when the video of Eric Garner’s death played repeatedly in the media. I thought both about our acceptance of the incursions of security-industry apparatuses and the experience of being cared for by the guards in moments of vulnerability. The notion of staging Imponderabilia without the guards was never seriously entertained by the museum, and the performers knew intuitively that this kind of risk was not something that an American institution of MoMA’s size would take on, even in the context of an exhibition that celebrated an artist for assuming exactly that kind of risk. So, the work became a performance of this acceptance and the experience, economy, and relationships that resulted from it. It is hard to speculate as to what could have been, how museum visitors would have handled the responsibility of an unpoliced relationship with the performers. As press accounts noted, even with the guards in place, visitors did cross lines with performers, including instances of touching. This became part of the work, as did the increasingly attuned and intimate choreography between the guards and performers.

Around its margins, the MoMA version of Imponderabilia was usefully, if dispiritingly, revealing. The choices that compromised the work, particularly the installation of the security guards, speak to points of crisis in both the microcosm of the art world and society at large: the institutional aversion to risk; the acceptance of a lack of trust between citizens, largely along race, gender, and class lines; missed alliances among different classes of labor; and the continued failure to equitably ensure even the most basic rights to bodily safety.

Coda: On the closing day of the exhibition, the performers and guards enacted a low-key ceremony of reversal. Standing in the now-empty sixth-floor galleries, one guard said he had always wondered about what it was like to perform Imponderabilia. With little pause, two guards took up the performers’ positions in the doorway. The performers lined up to walk between them, with the guards’ usual posts vacant. Performers moved between the guards, without rushing and without stopping, looking each other in the eyes as we passed. When it was over, we embraced, gave thanks, made promises, gathered our belongings, and moved on.