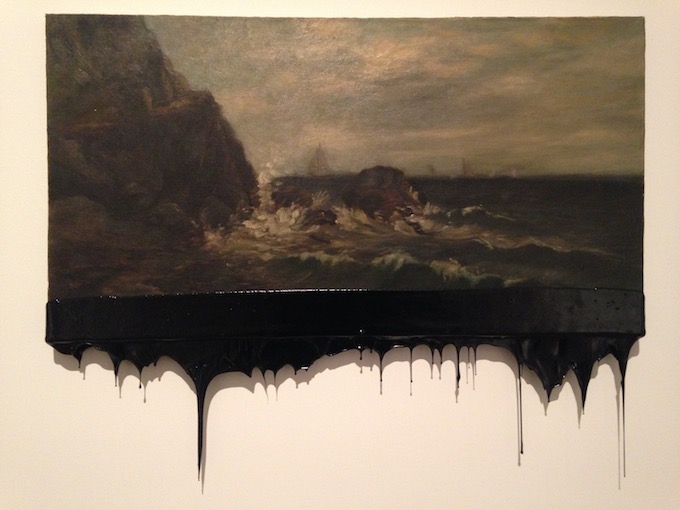

Minerva Cuevas. Offshore, 2014. Oil on compressed wood covered in tar; 40 x 36 ½ inches. Photo by the author.

Collapse: Abandoned to the indifference of physical nature, any neglected artifact disintegrates. Places too are social artifacts, architectural masses sustained in space by forms of life. When customs falter or vanish, the unsupported mass falls in on itself. Etymologically, “ruin” means collapse.

“Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought / As doth eternity”: Despite its fractured state, ruin remains a legible sign of ephemerality. Tableaux of disrepair have been conveyed to us—by despondent romanticism, modernist utopianism, total war, and now environmental catastrophe—charged with the negative knowledge of inevitable deterioration. Although literally powerless to affect what is already ruined, figurative language and imagery can recover from silence the outline of a muted address. Rilke contributed the most effective expression of this literary process by his ekphrastic sonnet “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” For the poet, the marble fragment evokes its own lost form, a lyrical reconstitution that culminates with the imperative, “you must change your life.”

Varieties of rubble: Etymology notwithstanding, ruin lacks a fixed definition in language or image. Practically and politically, our evaluation of it is inconstant: to be ruined is neither always lamentable nor always desirable. The criteria for what counts as a ruin or when something is ruined are uncertain and disputable. Rhetoric of ruin justifies a diversity of political programs. Exemplary critical projects of reclamation, like those of Hölderlin and Benjamin, coalesce in its figures. Its visual rhetoric has often aestheticized obsolescence; Joel Sternfeld’s phenomenal series of photographs of the Highline on Manhattan’s West Side played a crucial role in the successful campaign to renovate the disused elevated railway into a pedestrian mall and art destination in the gentrified industrial district. Images of natural rampancy stilled in eloquent equilibrium with fabricated uprightness suggest the naturalization of culture. Alternatively, Robert Smithson thematized an entropic stasis into which both nature and culture dissipate. This sort of letdown may prefigure more contemporary practices of impertinence and indifference (being a bummer, spoiling the fun) that perhaps hold the potential to ruin situations and undermine the authority of institutions and ideologies.

Scorpion-Bird Man (detail). Basalt; Tell Halaf, Syria. Pergamon Museum, Berlin. Photo by Genealogist, Wikimedia Commons.

Prior to the massacre at the Bardo Museum in Tunis: A damaged Neolithic sculpture of a winged scorpion with human features was recently on view in Assyria to Iberia at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York [see figure, Scorpion-Bird Man]. The massive basalt carving was excavated at Tell Halaf in northern Syria and later taken to Berlin. During an Allied air raid in 1943, an incendiary bomb struck the museum where it was stored and the superheated stone block shattered under the cold water dousing the blaze. After reconstruction, the sculpture is a maze of cracks and gaps and missing parts. When I viewed the piece, I first thought its condition unremarkable, even typical. I imagined it battered by centuries of desert wind, vast and austere like Baudelaire’s”ancient Sphinx omitted from the map/forgotten by the world, and whose fierce moods/sing only to the rays of setting suns.” The provenance of this broken object invalidated my assumption regarding the antiquity of the ruination of the ruins of antiquity. The degradation of many ancient artifacts is a recent phenomenon – not antique but contemporaneous to us. Today, these monuments to ancient idolatry—Nineveh, Nimrud, and Hatra—have been despoiled again.

Mislaying the ruin: Gilda Mantilla and Raimond Chaves, the exceptional Lima-based partners representing Peru at the Venice Biennale in the summer of 2015, have named their installation Misplaced Ruins. In the project Dibujando America (Drawing America) the partners traveled through South America, illustrating their experience with sketches and temporary murals. The artists knew that by depicting unfamiliar places they risked perpetuating historical misrepresentations and contemporary instrumental abstractions. To qualify their intent Mantilla & Chaves employed handmade processes like sketching and threading [see figure, Mapa sobre Mapa]. In their upcoming installation they will codify and de–territorialize “signs of belonging” from the landscape of Peru, including pre-Columbian ruins, under present-day conditions of global mobility and intangible communication. Ruin is “recoded” as a vestige of familiarity across an emergent landscape of shared uncertainty.

Gilda Mantilla and Raimond Chaves. Mapa sobre Mapa, 2014 (detail). Macramé thread, nails, wall; ephemeral wall mural installed at SITE Santa Fe. Photo by the author.

Rake to release: These days, ruin is more likely to appear as the outcome of a process than as an emblem of transience within a depicted setting. In 2008, Lee Mingwei reformatted Picasso’s Guernica (1937) as a Tibetan sand painting on the floor of the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art. Halfway through its exhibition, Mingwei invited the audience to walk across the granular surface of the image before he and his assistants raked it. The horizontal image of devastation was itself obliterated under a combined gesture made to sublimate suffering in an experience of non-monumental impermanence.

Tides: While Lee’s process of ruination follows a well-rehearsed logic of de-differentiation, the ruin practiced by Minerva Cuevas is strikingly pictorial and compositional. For the series Hidrocarburos (Hydrocarbons) (2010), Cuevas plunged an antique painting of the sea in chapopote—a petroleum tar common in Mexico—until the tar, rising like the tide, aligned with the depicted shoreline [see figure: Offshore]. Thus the chapopote appears to wash ashore and spill out of the painting and down the wall. Cuevas declares her intent by compromising (“hacking”) both nostalgic picture and toxic substance. The composite object dramatizes their opposition in a series of resemblances and reversals. The unframed painting and the fine tapers of black tar look to possess a common vulnerability, but the hardened drip of lustrous oil and the spray of crashing waves are hideously unlike. Cuevas’s act transforms the quaint image of nature into a degraded artifact of environmental unease. If it once seemed obvious that to make something look old you needed to ruin it, ruining something old may now be the best way to bring it up-to-date.