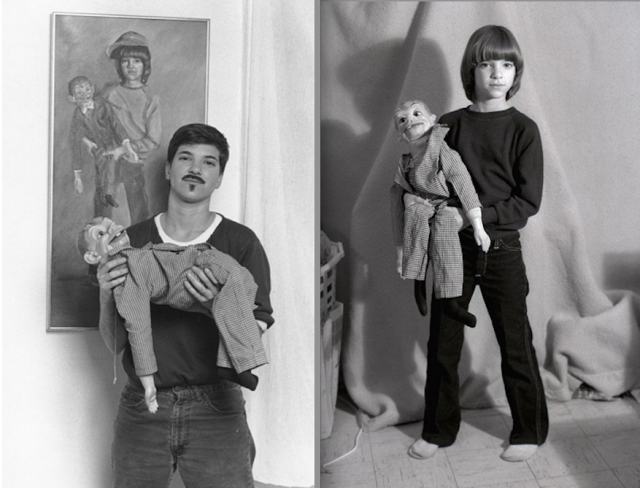

(left) Lisa Ross. Grown with Mortimer and Original Painting, 1993. (right) Lisa at 10 with Mortimer Schnerd, 1974; reprinted 1993. Both photographs by Susann Ross; silver gelatin print; 40″ x 60″. Courtesy of Lisa Ross.

In December 2013, I received a master’s degree in psychoanalysis at the Center for Modern Psychoanalytic Studies in New York, the same institute where my mother trained, starting in the fall of 1985, when she was pregnant with me. The courses were structured like process groups, and most of my professors had been her peers. Sitting in the Center’s brownstone in the West Village was fulfilling my inevitable calling.

After a few semesters, I wanted to rid myself of my mother, to not wear her so openly on my skin through this unavoidably distinct name and the anecdotes that I let leak out about my own childhood. Many of the papers I wrote were about the decaying relationship with my girlfriend at the time, but many were about my relationship with my mother. By the time I completed my thesis on Alina Szapocznikow, a Polish sculptor who died in 1973, I felt I had created my own space at the Center; I no longer inhabited hers.

More than a year after I’d finished the program, amid a break before my next phase of training, I sat next to my mother in a large, windowless conference room in the Hyatt Regency San Francisco, where the annual American Group Psychotherapy Association (AGPA) meeting was taking place. It was full of therapists of all kinds, from around the world, masterfully simulating a process group—what felt like a massive enactment of a regression. It didn’t feel bad, necessarily, just a little too familiar.

Later that night, my mother received a short e-mail from a patient, the photographer Lisa Ross. I had been aware of Ross’s work for some time; a book of her Living Shrines project is on my parents’ coffee table. Ross has exhibited widely. She had a solo show at the Rubin Museum in New York, and has been reviewed by the New York Times, Artforum, and the Wall Street Journal, to name a few. The note included a link to her work from the early ’90s, the Drag series, which neither my mother or I had ever seen. Laying in the queen bed in the San Francisco hotel room that we were sharing that night, I saw us reflected in the tiny little iPhone screen.

Lisa Ross. In the Looking Glass, Mother/Daughter, 1990; silver gelatin print; 20″ x 24″. Courtesy of Lisa Ross.

The photograph of Ross and her mother in bed was taken in Ross’s parents’ Miami Beach home in the early 1990s. The whole house was apparently mirrored—very ’80s Miami. At that time in New York, where Ross still lives, the drag king scene was just starting to come up in a real way [1]. Ross, an out lesbian entrenched in the queer community, had started to play with images of herself in different gender presentations, in her photography, outside of the nightlife realm in which this gender play was deemed acceptable. She employed the very controlled space within her photographs to explore the fantasy of crossing very off-limits boundaries.

Ross, in a set of nine images, manages to playfully address and simultaneously dismiss the questions of integration between a mother and a child—where one ends and the other begins—and the Oedipal conflict’s affect on developing sexuality and gender presentation.

As a lesbian, I have found it difficult to situate myself comfortably within the psychoanalytic discourse. There is, of course, important work by Nancy Chodorow, Jessica Benjamin, and many others about issues surrounding gender and sexuality within the psychoanalytic community. But there has been an active history of exclusion of queers, as well.

Development as it’s laid out in the classical psychoanalytic literature, is a progression, and I may have skipped the step of rejecting the mother and choosing the father as the desired object. Fundamentally, and may be as the product of long-term, internalized homophobia, I had the secret fear that I wasn’t born this way and that I never managed to resolve my Oedipal fixation, actually and finally separating from my mother.

The implication here is not that Ross’s image of herself in bed with her mother—that I first saw when I was in bed with my mother, Ross’s analyst—resolved any of these conflicts. But there is an ease that comes with play, an ease that relieves some of the tension caused by these conflicts. There is something of the uncanny in Ross’s images, rendering the level of intimacy a bit uncomfortable. But they also possess a fundamental humor in their honesty that manages to translate that this is what it is, and it’s impossible.

In the Drag series, Ross acknowledges these conflicts: how much of gender and sexuality results from the unconscious interaction between parent and child? Does the child’s presentation and preference eventually reflect some encrypted desire of the parent’s? How can we be sure where one ends and the other begins?—and simultaneously, they elegantly throw their proverbial hands up in surrender. There is nothing we can do but make the choice, over and over, to separate.

—-

[1] Maite Escudero-Alías, “Long Live the King: A Genealogy of Performative Genders,”. (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, December 18, 20082009), p. 87.