“Purge the world of bourgeois sickness, ‘intellectual,’ professional and commercialized culture; Purge the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic art—PURGE THE WORLD OF ‘EUROPANISM!'” [1]. Written with cambered handwriting, the first Fluxus manifesto was released in 1963 and clearly illustrated the movement’s mindset. Members of the Fluxus movement felt a deep sense of purification of their artistic practices, especially in their reconsiderations of music and sound art. During the mid-1960s golden age of Fluxus in the United States, spiritual communes across Southern California were formed to create their own utopias, purging existing notions of living correctly in favor of spiritual liberation, not unlike the Fluxus awakening. Frontiers of the new, as defined by these emerging generations of artists and spiritual seekers, claimed agency of their respective histories and collectively created meanings on their own terms.

Artists associated with Fluxus were heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism, a spiritual practice in favor of philosophies of impermanence, compassion, and acceptance. Resulting from the artists’ various purges, their avant-garde works transformed existing definitions of performance and music by equating art with living with profound absurdity.

With their manifesto, artists associated with Fluxus were enabled to perform acts of artistic rebellion, in order to shed the burden of ideology associated with consumer capitalism. In New York City, the New School offered classes such as “Experimental Composition,” first taught by John Cage, who would influence a tight-knit family of artists inspired by his famous 4’33” (1952), known as his silent piece. His students would take his brazen curiosity many steps further, with durational, improvised works driven by the Buddhist concept of sunyata, representing spaciousness, openness, and the void.

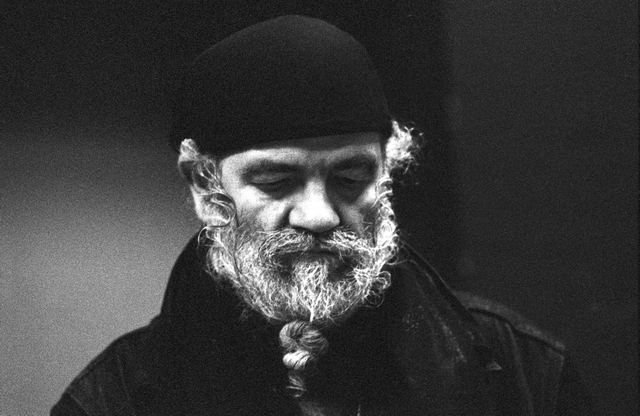

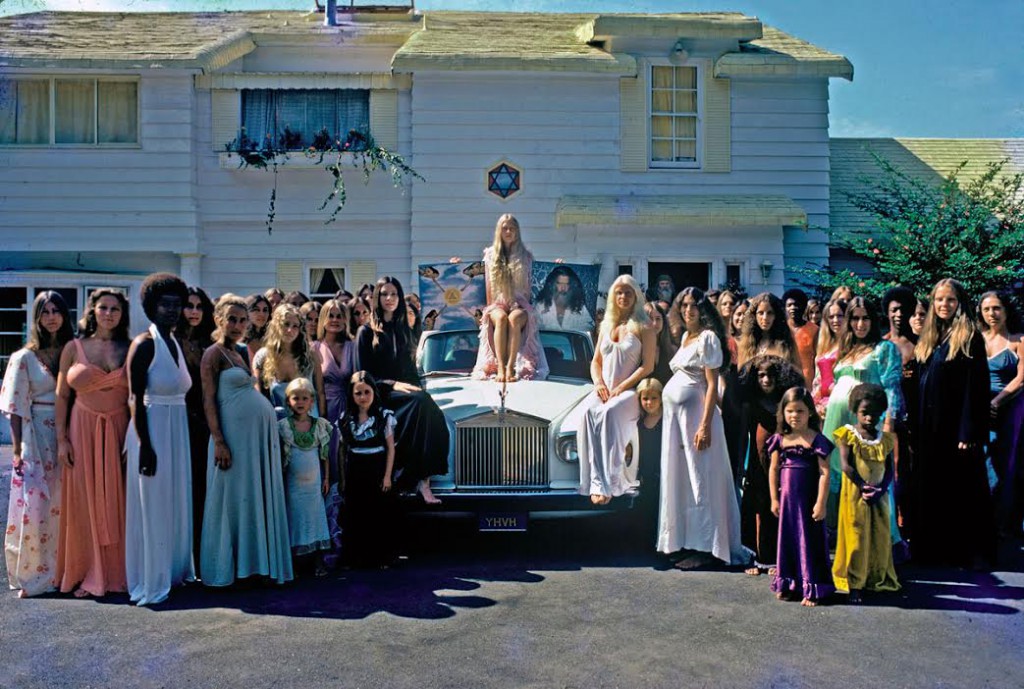

While East Coast avant-garde composers embraced possibility and liberation to redefine music, West Coast cults cropped up to liberate the spirit. The Source Family, the quintessential spiritual commune of Southern California, was formed in Los Angeles at the end of the 1960s. Widely recognized as a religious cult at its inception, the Family was led by the restaurant–tycoon–turned–patriarchal–spiritual–leader Jim Baker, otherwise known as Father Yod (and later, God) to his devotees. The Source Family’s tailored doctrine appropriated teachings from a number of world religions. Though the Source Family was short lived (lasting from 1969 to 1977), its legacy continues to pervade the region in the form of alternative, health–food restaurants and Kundalini meditation centers, such as Golden Bridge Yoga, that dot Los Angeles.

The Source Family, gathered for a portrait in front of the Father House. Courtesy of The Fox is Black.

The explorations of the Family’s insular, spiritual utopia were inevitably channeled into the arts, leading to the formation of the rock band, Yahowa 13. (To this day, psychedelia aficionados exalt the rare, experimental albums produced by the cult rockers of the Source Family.) After group meditation every morning, the members of Yahowa 13 would gather in their practice space, a garage at the Father House, to produce rhythmically appealing, improvised rock music interrupted by the abrasive chanting and pounding of drums coming from their intuitive leader, Father Yod. When I interviewed Isis Aquarian, the Source Family historian, she recalled the sessions as such: “Father had fun with it, as did the family — it brought us joy. It was exciting to create spontaneously and know it was the higher self connection with the cosmic.”His absurd interventions disrupted their harmonious instrumentation but allowed for a more pure form of music making.

Yahowa 13 performed with a mindset akin to that of the experimental composers of Fluxus. Several years earlier, in 1964, the Fluxus composer La Monte Young introduced his highly regarded improvisational composition, The Well-Tuned Piano, a pivotal piece that melded an array of subtly off-kilter notes with cascading lofty phrases and melodic fragments. These fragments were soothing, despite the unconventional progression of tones that broke away from the accustomed, Western, eight-note musical scales. Influenced by Indian classical music, and channeling the guidance of his avant-garde predecessors, John Cage and Richard Maxfield, Young asserted his authorship and publicly performed the piece for upwards of five hours. By embracing musical dissonance, the art-making approach of Fluxus and the Source Family liberated spiritual identities and mundane absurdities by breaking down the walls that separated art from the rest of their lives.

Today, the Source Family is regarded as a kitschy relic of California history and has become as well known in mainstream popular culture as the absurd Happenings and anti-art antics of Fluxus. Allan Kaprow, a veteran of Fluxus, pointed out the absurdity of the movement’s growing recognition, in a statement penned in 1961: “Some of us will probably become famous. It will be an ironic fame fashioned largely by those who have never seen our work.” Seeking direction within themselves and through each other, the artists of Fluxus related to one another with the sentimentality of a family, even when they were geographically separated. Resounding through history, the vast assemblage of experimental sound art from this era speaks volumes of the creators’ expanded consciousness, one characterized by mental fluidity, unbound by time.

—

[1] Clive Philpot, “Fluxus: Magazines, Manifestos, Multum in Parvo,” George Maciunas Foundation, https://georgemaciunas.com/cv/manifesto-i/.