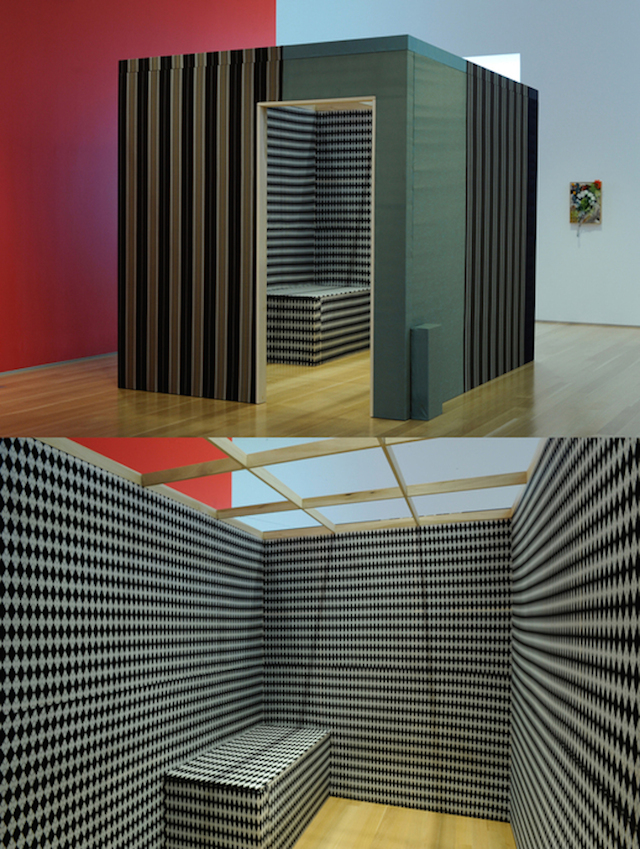

Rashawn Griffin. Fissure, 2013; fabric, wood, lighting fixture, speakers, sound (59:23); 88 x 129.5 x 155.5 in.

I first encountered the engrossing work of the multimedia artist Rashawn Griffin (b. 1980) in a 2014 group exhibition, The Center is a Moving Target, at Kemper at the Crossroads, in Kansas City, Missouri. Drawn into the glow of the interior habitat within Griffin’s sculpture, Fissure, I felt transported. I sensed that this was an artist interested in change—or in creating the sensation of being in many places, and feeling many emotions, at once. That hunch was later confirmed upon learning that Griffin had moved from New York City back to his hometown of Olathe, Kansas, in 2012, following a wave of success upon completion of his MFA at Yale in 2005, including his 2005–06 residency at The Studio Museum in Harlem and his inclusion in the 2008 Whitney Biennial.

In that biennial, Griffin displayed a series of sculptures and suspended-canvas works, featuring found-textile elements collaged upon their surfaces. Able to spread out in his studio in Kansas, Griffin has extended his interests in textile and architecture into larger and penetrable sculptures—often with ambient sound elements and lighting effects that disrupt one’s ability to easily locate identity or place—that imply family narratives and many cultural connotations. For this conversation, Griffin and I delve deeper into the intimate spaces of these enigmatic forms.

Danny Orendorff (DO): Your work indicates a great deal of interest in ancestry and heritage—both real and imagined—expressed through textiles. The tradition of designing tartans (or plaids) for Scottish and Irish kilts, for example—in which particular color pairings and patterning signify different family, professional, or social affiliations—connects textiles and identity in a really status-conscious way. In the patchwork of textile elements that you bring together, are you attempting to work out certain intersecting and maybe conflicting affiliations of your own?

Rashawn Griffin (RG): Exactly-ish. I Googled different Griffin-family tartans on a whim, and their relationship to identity seemed to parallel my understanding of quilts. You’re doing a better job explaining in asking the questions than I. Is representing the self a romantic cliché that people like to talk about because of some material affect, or can identity exist in an abstract object? I don’t know; it’s why I make stuff. Everyone wears fabric, but when you confront those objects, there’s no body but your own. I’m not sure if it’s about you or me, but that’s fine.

DO: Textiles are very intimate and personal. We wrap our bodies in them, like you say, making them potentially very erotic as well. While there’s a living-room-fort playfulness to your sculptures, I can’t help but read sexual possibility into the dimly lit passageways and narrow corridors within them, particularly when there are ecstatic interiors at the core. To me, you’re blending the slumber party with the sex club—and maybe they aren’t that different to begin with. Even the name of your 2012 solo show at the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, a hole-in-the-wall country, sounds like a rural, gay dive bar.

So, could you speak about the spaces, experiences, or sensations you have in mind when creating or designing these sculptures, which elude while perhaps referring to forms of Minimalism?

RG: Amazing—my favorite gay bars are the lone holdouts in communities where there is nowhere else to go. Everyone gets shoved together and they have to figure it out; young, old, black, white, and so forth. In other cities, and the United States in general, it’s easy to segregate. The art historian Kellie Jones introduced me to Nat Love’s autobiography, Life and Adventures of Nat Love, back in 2005, and “a hole-in-the-wall country” was a line from that book. But I began those sculptures really simply: asking what it would be like to be in a painting. I made some drawings of spaces I knew that were both intimate and public. Saunas, for example, have a ritualized way of interpolating the body in space.

I’m not a Minimalist; I wasn’t around during its time. The thing is, much of art history isn’t one’s own history. Once you come to terms with that, there is actually a lot more freedom to maneuver. If the history doesn’t fit you, invent your own.

DO: In that way, much of your approach to art making seems as homegrown and personal as the resulting objects. As you have been traveling and showing internationally quite frequently, what is your relationship to the domestic? Is it a concept or a real place? I wonder how the use of found textiles traces an itinerant domesticity—your portfolio itself as a home.

RG: I like the oxymoron implied in itinerant domestic. Assuming the domestic is fixed, it implies and highlights the disconnection, dislocation, and surreal aspects between the two words in that phrase. We wake up and go about our day, and we think it’s normal, but it’s not. If everyone had gypsum as pants and jeans on their walls, no one would think anything of it, either. Maybe your description is better—it sounds very Proustian.