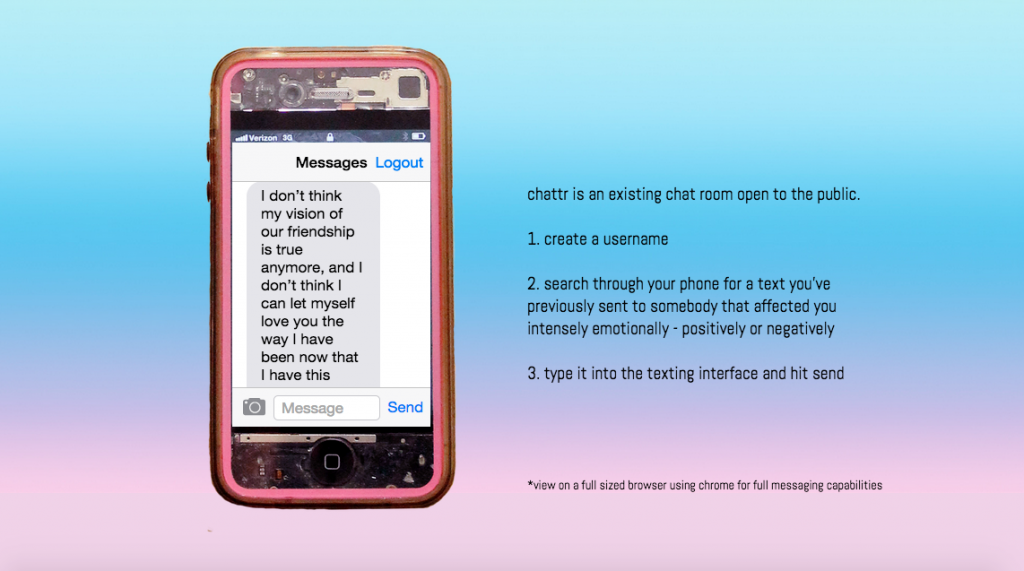

Cybertwee, “shared memory emotional infiltration” screenshot of performance. 2015. Courtesy of the artists.

During a particularly unpleasant heat wave this past summer, I had a fever dream in the middle of the day. A conversation was unfolding over my text messages with someone to whom I had briefly been close. The tone of our dialogue was apologetic but distressing, as if we were both trying to decipher the reasons for our falling out. The nuances of holding these text exchanges were subconsciously felt: the anxiety of waiting for a response while imagining the other party’s thoughts, lacking any telling eye contact or body language. The blinking, symbolic ellipses, fraught with impatience and uncertainty. Alarmed by how an ordinarily casual act was causing so much tension, and unable to tell if I was actually dreaming, I awoke abruptly, searching for my phone in a hazy panic. I found it in its usual place, under my pillow, awaiting my command.

Perhaps by pure necessity, contemporary life in a capitalist information society dictates the prevalence of the archive. Traditionally referring to a meticulous shelter for the conservation of objects—such as a library or museum collection—an archive is now instinctively personal. Text threads, however dated or immense, can be effortlessly summoned, and public declarations on social media, however branded or filtered, authenticate that nostalgia is an ever-evolving document. Memories are monetized, and as Facebook’s algorithm solicits users to re-share previously posted content, our past selves seem decidedly reincarnated by the corporations that own our data.

Compelling in their relevance and urgency, these themes have generated an insurgence of new digital projects. Among certain artists, a confessional attitude and a willingness to disperse personal archives is a seditious plea against marketing rhetoric. Paraphrasing this ethos, sharing shouldn’t foremost be incentivized by its potential commodification.

https://t.co/21aaWhLsAN pic.twitter.com/M7vmUZBszl

— so sad today (@sosadtoday) July 10, 2015

The interactive work, shared memory emotional infiltration, hosted on the publishing platform NewHive by the feminist art collective Cybertwee and artist Molly Soda, enables visitors to retype a previously sent text message within a public chatroom. Through an interface designed to mimic a used iPhone, the artists asked for immediate reinterpretations of emotional language. Meant to elicit shadowy memories of experiences, this iPhone’s transparent glass acts as evidence of a digital life inhabited and possessed by the realities of existence. We are all archivists; we carry our archives with us.

Although the work’s desktop interface cannot convey the physical intimacies of holding a smartphone, through it a certain remembrance lingers. The ritual of grasping a ubiquitous object to impart a transference of memory carries with it an unexplained sentience, a sort of uneasy déjà vu, similar to what I had experienced in my dream. This work offers participants a sympathetic, uncensored point of view through sharing private messages with strangers. Caring for our digital objects, and their contents and methods, means accepting these systems as embodiments of our personal experiences. In his essay, “Archivist Manifesto,” the Chinese theorist Yuk Hui positions the personal archive as an extension of the psyche in a Foucauldian sense, meriting responsibility and cautious protection. Hui writes: “Care is not only, as we say in our daily life ‘taking care of something’ but also a temporal structure that creates a consistent milieu for ourselves…At the heart of the question of [the] archive is the question of care, and in order to care, one must think of the archive as the exteriorization of our memories, gestures, speeches, movements.”[1] In this vein, archiving can instead become a practice of self-care to a demographic of individuals conditioned to self-actualize through data dissemination. Subliminally transcending traditional notions of care (say, the physicality of touch) within networked digital spaces is the needed association that could liberate our digitally encoded memories from their capitalist constraints to resemble individuality, thus abandoning collective efficiency in favor of a more unique self-awareness. Hui’s manifesto continues to call for a development of a noncommercial platform that could allow “archivists” rather than “users” to freely share personal data, suggesting welcoming parallels to the passé notion that Internet interactions cannot result in close relationships.

happiness got cancelled

— so sad today (@sosadtoday) June 2, 2015

Known for its pith, Melissa Broder’s ongoing Twitter project @sosadtoday presents a self that fluidly merges with virtuality. Driven by the allure of this ironically depressed persona, followers of the artist seek alleviation for the born digital’s inherent anxiety: what is the meaning of real life? Even with each Tweet being surveilled and converted into metadata, shuffled into an archive of its own pseudonymous isolation, Broder and her audience together build entwined connections through the commonality of networked language. In broadcasting her melancholy, and making it emotionally accessible, her followers can heal, possibly finding spiritual consolation.

For me, the fundamental difference between a memory that’s triggered from re-encountering archived data and one that’s triggered by an object or situation is the technological assurance that I have already lived that memory: I am experiencing a meta-reflection, reflecting on something I have already reflected on. This produces an aura of solitude. In creating cognitive distance from a newsfeed’s hyper-current stream, re-visitation feels secretive, as if I am exploring a past self, void of present networks or observation. In moments of insecurity, such as the loss of a friendship, the ability to refer back provides comfort. Maybe, with a bit of alacrity and a belief in this process, our archived memories can attempt to recall in us something akin to happiness.

———–

[1] Yuk Hui, “Archivist Manifesto,” Mute, May 22, 2013, https://www.metamute.org/editorial/lab/archivist-manifesto.