Last year, as part of ART21 Magazine’s “Revolution” issue, feminist new genre painter Anne Sherwood Pundyk rewrote the lyrics to Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” to create “The Revolution Will Be Painted.” Named after one of her large scale, latex and acrylic works, the collection of phrases from artists, writers, art historians and critics advocated for the crucial role that the visual arts—especially painting—play in propelling social change. This year, she’s looking back on the months that followed the creation of her anthem and eponymous painting, investigating the ways in which expressive abstract color creates a revolution of its own.

Anne Sherwood Pundyk Mattituck Studio. Photo credit: Andrew Berman Architect. © Andrew Berman Architect 2015.

Which came first, the revolution or the painting? Actually it was the drop cloth under a painting-in-progress that sparked my revolution. More precisely, late in the summer of 2014, I was in the process of moving my studio to a place where I could spend days on end working in a rural environment—a place pulsing with natural life. I looked down and realized the configuration of spilled paint and blue masking tape X’s inadvertently generated on the plastic tarp protecting the floor of my new studio was more compelling than the stretched linen piece on which I was working. The tarp’s large scale and language of pure color presented a way to embody the unpredictable natural forces around me. Upon returning to the city, I felt myself succumbing to the charms of the accidental Rorschach blots aligned with small, crisp crisscrosses I had just seen in Mattituck. I started what would become the painting, The Revolution Will Be Painted, (TRWBP), on a 12 by 15 foot canvas tarp on the floor in Tribeca.

Anne Sherwood Pundyk. The Revolution Will Be Painted, 2014. Latex, acrylic and colored pencil on unstretched canvas; 12 x 15 feet. Courtesy the artist and Christopher Stout Gallery, New York. © Anne Sherwood Pundyk 2015.

Looking back over the year since finishing the resulting unstretched painting, I can trace the transformative powers I first felt looking down at the plastic sheet on the floor of my studio. The painting itself, composed of large freeform pools of indigo latex paint interlaced with multi-colored vertical parallel zig-zag bars held in place by a vast field of bright red adjacent to a plot of raw canvas, is a conduit for wild thoughts, feminist discussion and action. Created on the heels of several years spent engaging in provocative collaborative publications and performances, I had learned to take risks, get up when I fell, and most importantly how to trust my intuition. Working with artists such as Suzanne Lacy and Bianca Casady had taught me about speaking out and the role of dialogue as a means of implementing meaningful change. My new painting incorporates these lessons.

“The Revolution Will Be Painted” video reading by Anne Sherwood Pundyk and Julia Winser Fiorino as part of HYSTERIA Magazine NYC Launch, OtionFront Studios, Bushwick, NY, September 3, 2015. © Anne Sherwood Pundyk 2015.

TRWBP is more than a single painting. It is my anthem, my signature—the place my art, politics and personality intersect. It says, “Be badass.” It keeps me thinking, painting, and moving forward. The premise behind my first essay on revolution for this magazine was a simple call to action: showing is better than telling and doing is better than showing. It is homage to Gil Scott-Heron’s song, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” (1970) advocating Black Power. In crafting my version of Scott-Heron’s verses I scrounged through 30 or 40 books and articles on art history and criticism, looking for specific language describing the transformative power of painting. I spotted and snatched revelatory phrases and collected the voices of many writers to form a chorus of “stolen” ideas. I wanted to show that the lessons for survival of the self are there for the taking; our history has yet to be written.

“The Revolution Will Be Painted” Paint/Dance Performance by Leah Raphael Curtis, Samadhi Arts Launch, Brooklyn, NY, August 29, 2015. Courtesy Leah Raphael Curtis and Samadhi Arts.

That essay empowered me to build on the discoveries uncovered in the first TRWBP painting, and has given the painting a life as a Zelig-like backdrop for my feminist community. The painting went first to a gallery exhibition in New York’s Lower East Side. During that show TRWBP became the staging ground for a suite of radical feminist performances and consciousness raising circle discussions. It has been central to my involvement in a steady stream of events, panels, performances and publications including artcritical and the London based feminist quarterly, HYSTERIA, whose editor, Bjørk Grue Lidin, selected the painting for the cover of the magazine’s fifth issue. During the New York launch of that issue in the fall of 2015, I did a video reading with my sister, Julia Winser Fiorino, of my ART21 Magazine anthem, while showing a stop motion documentary of the making of TRWBP. Also last fall, Leah Raphael Curtis integrated the painting into a dance performance for the launch of Samadhi Arts in Brooklyn—a platform for social transformation. Early this winter, I was asked to discuss the painting, in the context of feminist activism, in an interview with Jade French for a new arts publication, Contemporary Zine, launched at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.

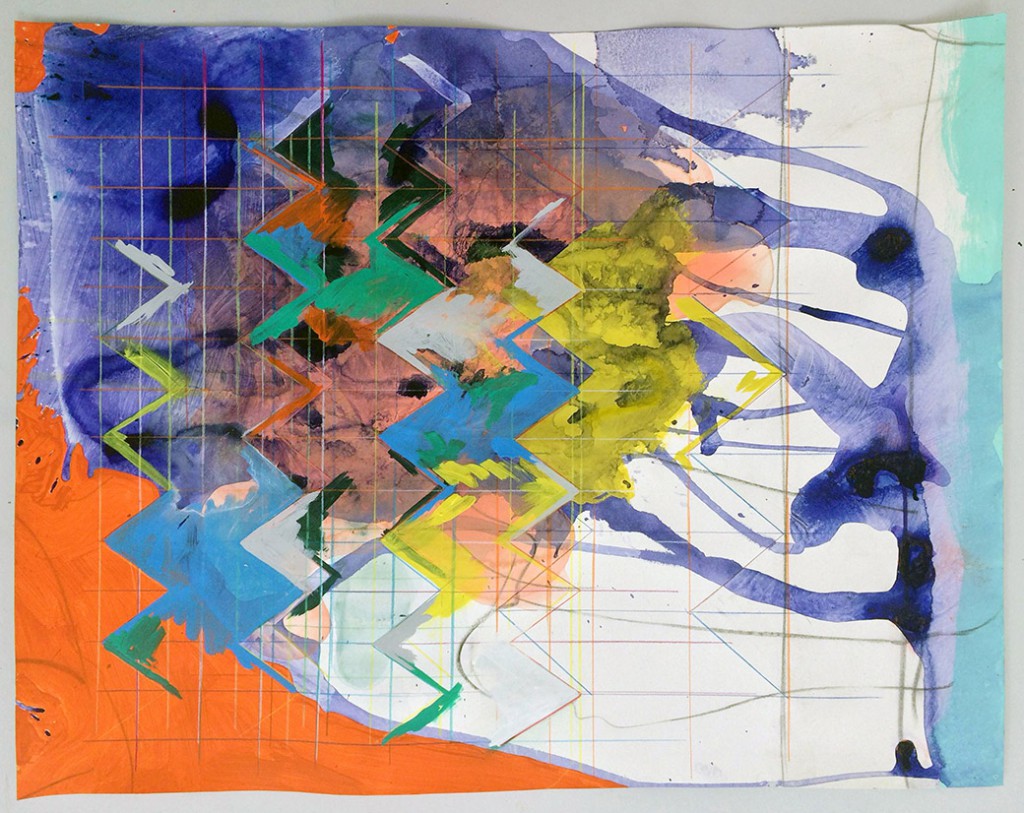

Anne Sherwood Pundyk. Wind O, 2015. Latex, acrylic and colored pencil on unstretched canvas; 86 x 95 inches. Courtesy the artist and Christopher Stout Gallery, New York. © Anne Sherwood Pundyk 2015.

Anne Sherwood Pundyk. Yours and Mine, 2015. Latex, acrylic and colored pencil on paper; 28 x 36 inches. Courtesy the artist and Christopher Stout Gallery, New York. © Anne Sherwood Pundyk 2015.

In the meantime my studio work continues to evolve as I happily remain under its spell. I will be showing a suite of new large canvas paintings in a solo exhibition at Christopher Stout Gallery, New York this coming spring. This work channels deeper into the expressive possibilities of unruly abstract color. In these works, “Painting will no longer create space as a theatre, it will give space itself a theatre”1—to quote a line from my essay. Adah Rose Gallery in Kensington, MD will also be presenting a solo show of new works early next year.

I recently spoke about my painting to a group of curatorial students at Marymount Manhattan College’s art department. Once again, I turned to TRWBP. I asked the 16 students to read the anthem aloud collectively, passing it from person to person. Next, going from speech to action, I invited the class to follow my instructional calls during two square dances. Everyone moved together through the sequence of patterns, merging each of their individual performances into a unified flow. Scott-Heron’s lyrics retain their capacity to agitate because locked into their rhythm and rhyme is a challenge: Take a step back, his words instruct, and question your assumptions. Scott-Heron’s message is encoded within the spills and patterns of my paintings. Signify. Represent. Painting is the revolution.

Marymount Manhattan College Guest Artist Lecture by Anne Sherwood Pundyk, “Painting and Activism,” with video screening and square dancing, November 11, 2015. Courtesy Hallie Cohen, Chair of the Art & Art History Department, and the college, and the students in the NYC Seminar class, “Curating the City.”

Anne Sherwood Pundyk. Diving Bell, 2015. Latex, acrylic and colored pencil on unstretched canvas; 82 x 92 inches. Courtesy the artist and Christopher Stout Gallery, New York. © Anne Sherwood Pundyk 2015.

- Clement Greenberg, “Cezanne,” in Art and Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 54.