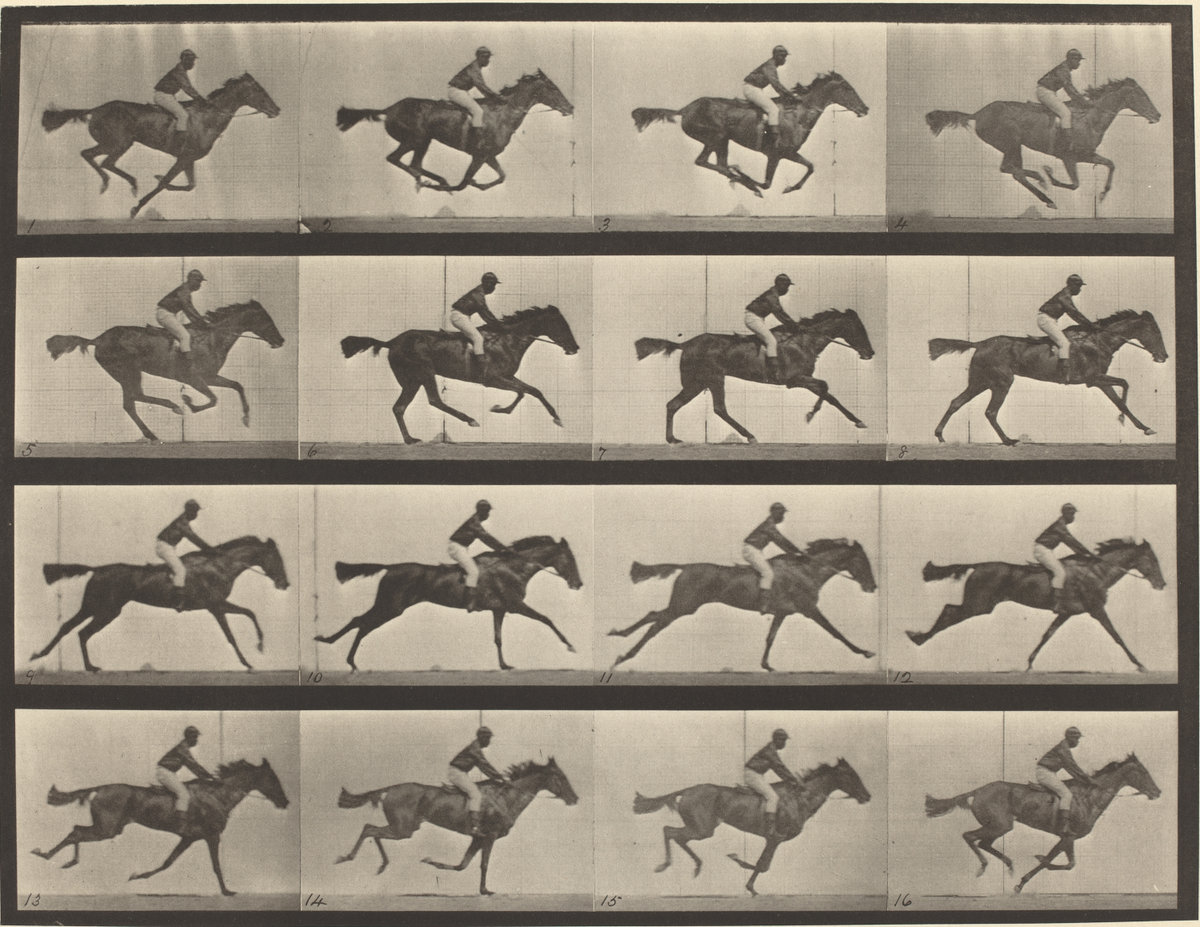

Eadweard Muybridge. Horse galloping (Plate 626), Animal Locomotion, 1887. Collotype photograph. Courtesy of National Gallery of Art. Open access image in public domain: PD-1923.

We live in a fast-paced, ever-changing world, and as such we are constantly moving our head and eyes around. Yet photography, since the mid-1800s, has offered a way to hold time still and capture the moment in a seemingly permanent form. From crisp, stop-motion images to blurry, long exposures, photography has enabled both artists and scientists to see the world in a way that previously was not available to the human eye. The static medium’s capability to represent movement remains compelling.

Eadweard Muybridge was the first to photograph precisely how animals move. In 1872, he settled a bet made by Leland Stanford, the railroad magnate, who argued that his prized trotting horse, Occident, had all four legs off the ground at some point in its gait. Muybridge placed a series of cameras along a racetrack, and a thread attached to each shutter was strung across the track. When the horse ran along the track, it broke the threads, tripping each shutter in succession and thus giving Muybridge a stop-action sequence of the animal’s motions. Stanford’s claim was affirmed: Occident did have all four legs in the air at a certain point. Muybridge went on capturing images of horses at various gaits as well as the movements of many other animals—including humans, from gymnasts to the physically impaired. Muybridge’s photography enabled scientists to study animal movement with exquisite clarity and artists to depict rapid motions, such as that of racing horses, more realistically.

Inspired by Muybridge’s work, the French scientist Étienne-Jules Marey built a camera that could shoot twelve frames in rapid succession onto a single piece of film. The camera looked like an old-fashioned machine gun. Marey would aim the device at a moving object, pull a trigger, and record multiple shots of the object, each slightly displaced. These images offered compelling representations of the mechanics of motion, such as the positions of a bird’s wing during flight. Scientists marveled at the way Marey’s images depicted the flow of movement. Marcel Duchamp’s painting, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, paid tribute to the artistic quality of these multiply exposed chronographs.

Étienne-Jules Marey. Bird Flight, Pelican, 1886. Open access image in public domain: PD-1923.

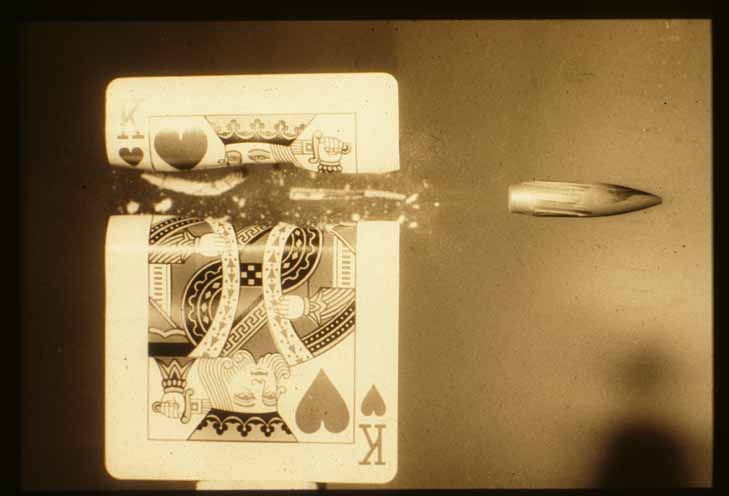

During the latter half of the twentieth century, Harold Edgerton, a professor of electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, extended the work of Muybridge and Marey and became famous for his artistic and scientific studies of stop-action photography. He captured fleeting instances of time using electronic flashes with exposures lasting only ten microseconds (1/100,000th of a second) and repeating them at stroboscopic rates of 120 flashes per second. His camera-and-flash arrangement was so precise that it could capture the instant a balloon burst or, as shown in the figure, a speeding bullet after it pierced a playing card. These images are fascinatingly surreal, for they reveal to us common objects as never seen before.

At the same time Edgerton was experimenting with stop-motion photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson walked the streets of Paris and other locales with his inconspicuous 35-millimeter camera and captured extraordinary moments of ordinary people doing ordinary things. One of the most prominent photographers of the twentieth century, Cartier-Bresson depicted the dynamics of life through his creative ability to identify and make indelible what he called “the decisive moment.” This phrase was used for the English title of his photographic book, Images à la sauvette (“images on the sly”), originally published in French in 1952. He snapped one photograph, Hyères, France (1932), from the top of a curving staircase as a bicyclist sped by, down on the street. In another photograph, Behind the Gare St. Lazare (1932), he captured the precise moment of a man in mid-jump across a large puddle. In both works, moving objects are out of focus, which accentuates the dynamics of the scene. In contrast to the precise clarity of Edgerton’s images, Cartier-Bresson depicted movement with blurs. These images are so expressive—both visually and emotionally—that one feels the need to conjure a story about the individuals portrayed.

Harold Edgerton. Bullet Through King of Hearts, ca. 1964. Vintage gelatin silver print. The Edgerton Digital Collections (EDC) Project. Courtesy of MIT Museum.

We sense movement in a variety of ways, though exactly how the brain performs this feat is not fully understood. In photographs, moving objects often appear as unfocused blurs because the exposure duration is long enough to record the trajectory of an object that streaks across the field of view. The brain doesn’t record motion in terms of discrete frames; in everyday experience, fast-moving objects, such as the rotating blades of a ceiling fan, appear as blurs. In artistic renderings, intentionally blurring the depiction of a moving object enhances the sense of movement. This fact was made apparent by animators who discovered that a cartoon character’s movements appeared jerky and unnatural if they drew them with sharp clarity, such as Road Runner’s legs as he speeds across the desert. Blurring the drawings made rapid movements look more natural.

How do we sense movement in a static, stop-motion photograph when there are no perceived cues, such as blurring? We must appreciate the significant role that prior knowledge plays in sensing movement. That is, we know what certain objects look like when in motion, and we know about natural forces, such as gravity. Thus, when we see a photograph of the dynamic posture of a baseball pitcher in the act of throwing or an Olympic diver in a mid-air somersault, we sense motion, because we know from prior observation that the individual is in the act of moving. When we see such photographs, including Cartier-Bresson’s shots of decisive moments, the sense of movement is so compelling that we can almost feel it. Photography has provided a means of seeing movement in a static image, and artists have creatively played with that sense of embodied feeling, both relying on and expanding our shared knowledge about a dynamic world.