Damon Davis. Untitled, from Negrophilia series. Bookprint, ink, watercolor, and adhesive, 2015.

For centuries, artists of color have been largely excluded from major institutional collections in the United States. A recent New York Times article spotlights growing efforts to correct this legacy of neglect and incorporate more artwork by Black artists into the permanent collections of various institutions. In the article’s closing statement, Thelma Golden, Director of the Studio Museum in Harlem cautions that “progress is not simply about numbers, but understanding this work, in the context of art history and museum practice, as essential.”[1]

Golden’s caveat reminds us that in spite of these reported efforts to increase racial equity in national collecting trends, statistics alone do not signal substantive recognition of these works “in the context of art history and museum practice.” In the aforementioned NYT article, numbers—the tally of artists/artworks or comparable market prices—are the primary benchmark by which racial progress is measured. However, these seemingly positive figures do not address the lingering structural issues that persist in the art world. Deploying these numbers as evidence of progress can deflect attention away from much-needed critiques of the institutional systems and policies that have made it possible for these artists/artworks to be excluded for so long. By point of fact, the Black artists who are now so sought after by many institutions are older (now, critically acclaimed) icons who were ignored in their youth, not unlike the way that major museums still overlook young Black artists today.

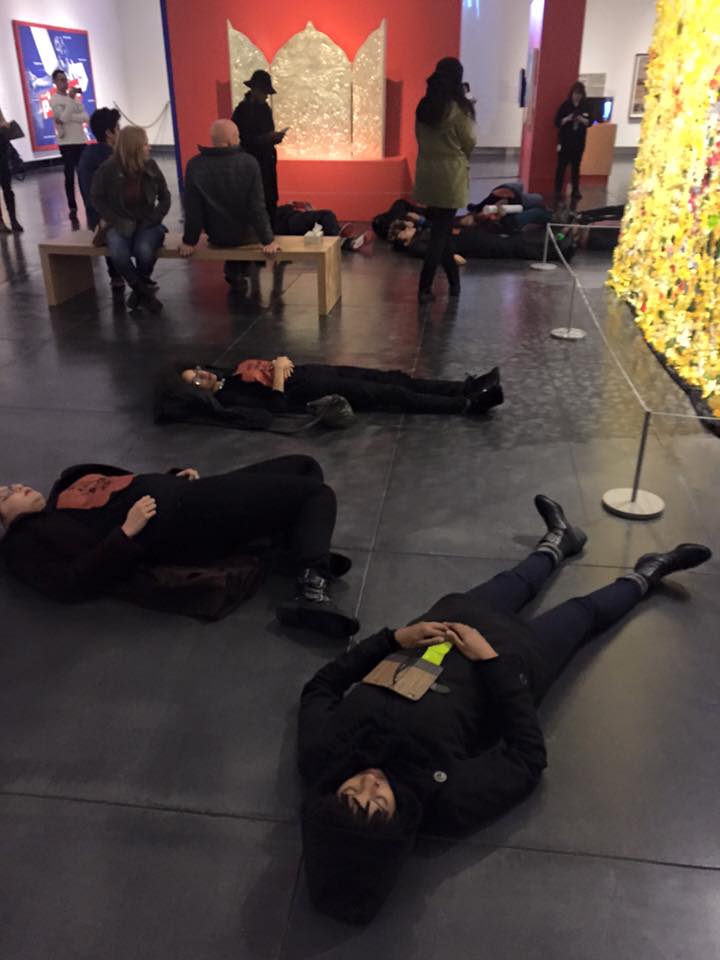

One would be remiss not to situate these shifts in collecting trends in relation to the recent prominence of the Black Lives Matters (BLM) movement.[2] Rooted in longstanding Black Liberation Tradition, BLM’s emphasis on racial justice is ideologically aligned with demands for racial equity in the contemporary art world. The rhetoric (end to the erasure of Black lives and experiences) and the tactics (protests and die-ins) made popular by BLM were deployed in response to recent episodes wherein young artists and audiences accused gatekeeper institutions of racial erasure. In December 2015, a group of activists organized by the Tacoma Action Collective organized a die-in to protest the marginalization of Black experiences[3] in “Art AIDS America”, a recent exhibit at the Tacoma Art Museum that intended to “[introduce] and [explore] the whole spectrum of artistic responses to AIDS.”[4] In this staged in-gallery protest, participants demanded that the museum “Stop Erasing Black People.” Importantly, even the nominal inclusion of young Black artists in predominantly white institutional art spaces does not translate into substantive representation. Case in point: the circumstances that led HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?, a collective of predominantly black and queer artists, to withdraw from the 2014 Whitney Biennale suggests that some young Black artists may find the ideological cost of participating in uncritical (yet illustrious) art spaces unattractive.[5] Certainly, not all artists of color are concerned with anti-racist institutional critiques, but for those who are, these concerns are often reflected in their art practice and production. It is unfortunate that institutions targeted by these critiques lack the will and agility to substantively respond to these critiques.

The actions and responses of these young artists and audiences are good barometers by which to judge the substance of perceived shifts within the art world. These, and other, incidents suggest that in spite of the apparent uptick in collecting the work of Black artists, crucial institutional changes still have not come to pass.

Tacoma Action Collective. Die-in Protest at Tacoma Art Museum. Decmeber 2015. Courtesy of Tacoma Action Collective.

[1] Randy Kennedy. “Black Artists and the March Into the Museum.” 28 November 2015.

[2] That is, these shifts in collecting trends may be the result of the public dialogues around race that have been instigated by BLM activities, rather than an organic transformation borne from considered, institutional critique.

[3] CDC, “HIV Among African Americans.”

[4] On view at the Tacoma Art Museum (1701 Pacific Avenue, Tacoma) October 3, 2015 – January 10, 2016: Tuesday thru Sunday, 10 am–5 pm.

[5] Eunsong Kim And Maya Isabella Mackrandilal. “The Whitney Biennial for Angry Women” April 4, 2014.