Editor’s note: This article is the first in a new column titled The New Situationists.

John Giorno reads “Everyone Gets Lighter” (video stills). Credit: Rikrit Tiravanija. Courtesy of YouTube.

New Year’s Day brings a unique brand of church revival to the East Village. Since 1974, the first day of the year has also marked the return of The Poetry Project’s Annual Marathon Reading: a twelve-hour series of performances that the organization describes as “an avenging engine of resistance and eager vehicle of the nascent year.” The marathon serves as a core fundraiser for The Poetry Project, the celebrated nonprofit founded at St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery in the summer of 1966. With a mission focused on the reading and writing of contemporary poetry, the Project also serves as a critical link in fostering dialogue and collaboration between poets and artists.

This year, attending the marathon for the first time, I watched poets, musicians, and performance artists present works ranging from political and reverent to awkward and hilarious. The schedule was packed with a steady flow of twelve to fifteen performances taking the stage every hour, creating a slightly chaotic, buzzing scene for audience and performers alike. I’d lost count as a poet stepped up to the mic, introducing his 2015 piece, “God is Man Made.” As he began to speak, I was drawn by his unique cadence, marked by large, expressive breaths, and the movements of his shoulders, legs, and gesticulating hands. He repeated certain lines three, maybe four, times in his rhythmic chant, and I was caught in the spell.

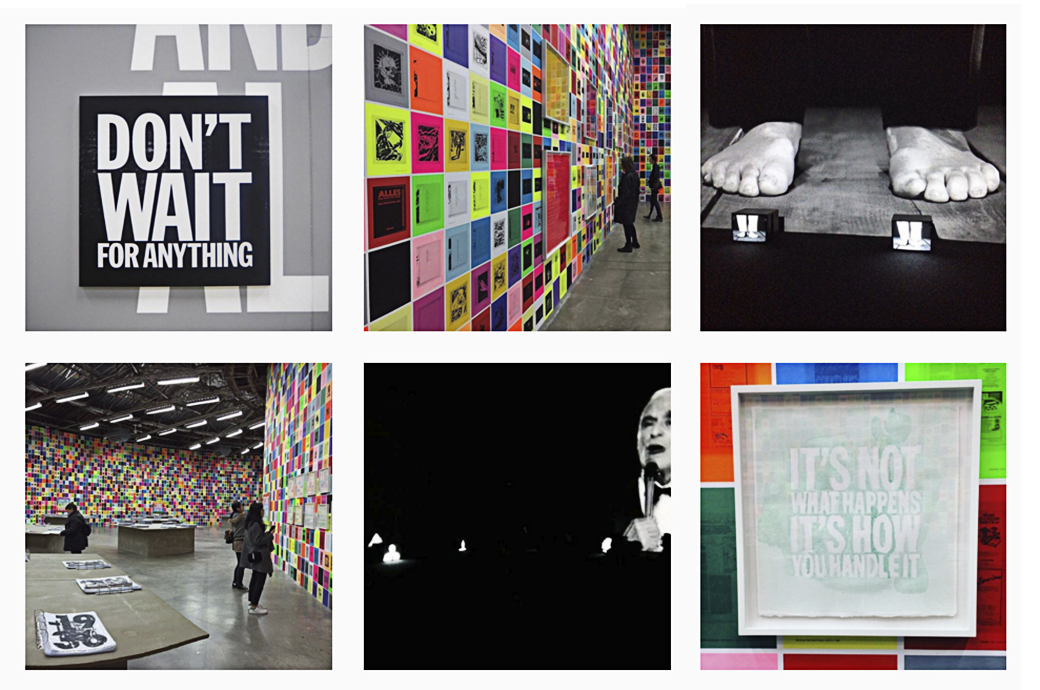

#JohnGiorno, 2016. Courtesy of Instagram.

The voice belonged to John Giorno, the multifaceted poet and artist with a career spanning five decades in New York. An important figure in the Factory art scene (he was Andy Warhol’s lover for a time and the subject of a number of his films, including the 1963 Sleep), he rose with the Beat Generation and gained recognition as a pioneer in performance poetry. A contemporary of many significant writers and artists from the 1960s, he also established Giorno Poetry Systems and the Dial-A-Poem project to publish and promote the work of others, such as William S. Burroughs, Patti Smith, and Laurie Anderson. The poet has since witnessed the radical transformation of the Bowery over five decades, as his living space and studio have expanded into a few lofts in one building located a stone’s throw from the New Museum.

While the poet was no stranger to the role of muse in the underground New York scene of the ’60s, arguably it was not until decades later that he would discover his greatest champion and collaborator. In 1997, Giorno met Ugo Rondinone, a Swiss mixed-media artist, twenty-eight years his junior. Rondinone approached the poet after one of his readings, inviting him to collaborate on a sound installation. The meeting would prove to be the genesis of an ongoing creative and romantic partnership. Last fall, the pair garnered much attention with the critically acclaimed retrospective of John Giorno’s life and work at the Palais de Tokyo, entitled UGO RONDINONE : I ♥ JOHN GIORNO.

Exhibition View, UGO RONDINONE : I ♥ JOHN GIORNO, Palais de Tokyo (10.21. 2015 – 01.10.2016). Photo credit: André Morin Scott Kin. Courtesy of Palais de Tokyo.

For this exhibition, Giorno entrusted his partner to curate items from a detailed personal archive dating back to the 1960s and containing more than ten thousand items, making public much of this personal information for the first time. The show was conceived and organized by Rondinone with a personal and collective sentiment clearly outlined in the title: whether revisiting known pieces, revealing unknown gems from the archive, or introducing new works, the retrospective celebrated the varied oeuvre of an innovator known and loved as poet, performer, activist, and artist. Organizing the exhibition into eight chapters, Rondinone was tasked with presenting a different facet of Giorno’s expansive work in each.

Ugo Rondinone is an artist known for his wide-ranging use of materials, moving with ease from drawing and painting to massive sculptural installations. Text is woven into the work of both artists—in some cases, the same words. The titular phrase of the work, Everyone Gets Lighter, is spelled out in one of Rondinone’s large, rainbow-colored neon arc sculptures; a poem by Giorno shares the title. Thinking about the poet’s archive, personally curated over the course of fifty years, and his decision to release its contents in one fell swoop, one feels his words speak to the sort of renewal that comes with the experience of letting go.

Ugo Rondinone, Everyone Gets Lighter, 2004. Courtesy of Gladstone Gallery.

Life is lots of presents,

and every single day you get

a big bunch of gifts

under a sparkling pine tree

hung with countless balls of colored lights;

piles of presents wrapped in fancy paper,

the red box with the green ribbon,

and the green one with the red ribbon,

and the blue one with silver,

and the white one with gold.

It’s not

what happens,

it’s how you

handle it.

You are in a water bubble human body,

on a private jet

in seemingly a god world,

a glass of champagne,

and a certain luminosity

and clarity,

skin of air,

a flat sea of white clouds below

and the vast dome of blue sky above,

and your mind is an iron nail in-between.

It’s not

what happens,

it’s how you

handle it.

Dead cat bounce,

catch

the falling knife,

after endless shadow boxing

in your sleep,

fighting in your dreams

and knocking yourself out,

you realize everything is empty,

and appears as miraculous display,

all are in nature

the play of emptiness and clarity.

Everyone

gets

lighter

everyone

gets lighter

everyone gets

lighter

everyone is light.

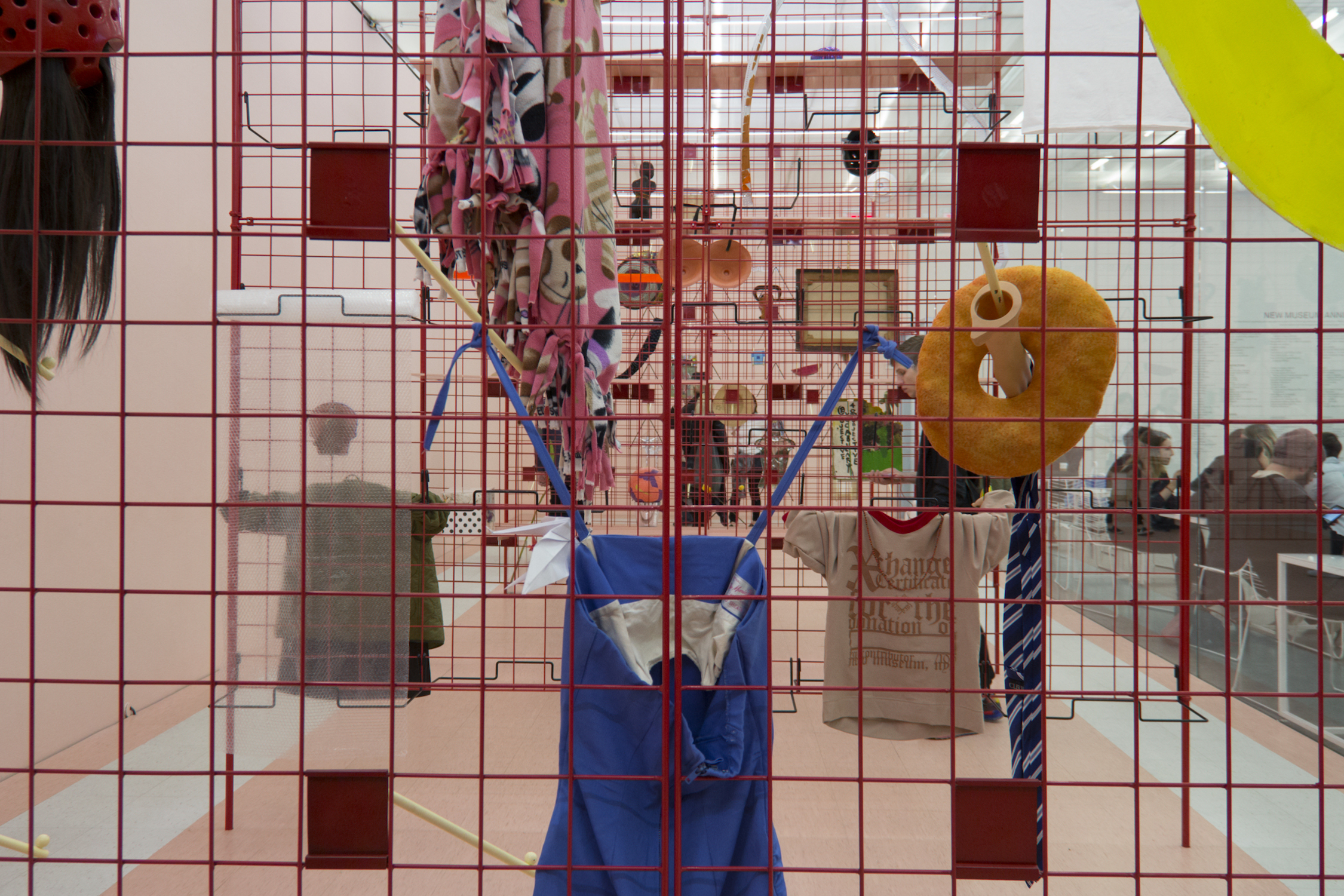

A couple of weeks ago, I walked down the Bowery to check out Pia Camil’s installation, A Pot For A Latch, a work that conveys a similar sense of renewal in the lobby of the New Museum. My visit coincided with one of the show’s “exchange days,” when the public may participate in the ongoing creation of Camil’s piece by exchanging personal objects of significance for others in the installation. As the artist’s invitation explains, “The monetary value of these items is insignificant; their value lies instead in their richness of meaning and in the new life that they acquire on the grid within the Lobby Gallery.”1 As I listened to a few visitors gingerly offer their objects and stories to the exhibition’s curators, I was struck by the coincidence of Giorno’s building across the street and thought again of his archive on display and subsequent revival: everyone gets lighter; everyone is light.

Pia Camil. A Pot for a Latch, 2016. Exhibition view: New Museum. Photo credit: Erin Sweeny.

Pia Camil. A Pot for a Latch, 2016. Exhibition view: New Museum. Photo credit: Erin Sweeny.

1. “Pia Camil: A Pot for a Latch,” New Museum, accessed March 15, 2016, https://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/view/pia-camil.

Editor’s note: This article is the first in a new column titled The New Situationists, by ART21 contributor Erin Sweeny:

A few years ago, I contributed an article to the Praxis Makes Perfect column entitled “New Situationist City.” The article discussed the artistic and political movement known as Situationist International (SI), founded by French intellectuals in 1957 to resist consumerist tendencies related to capitalist society and the influence of mass media. Equating technological advancement and increased leisure with social alienation and growing dependence on commodities, their aim was to “counteract the spectacle.” By deliberately constructing situations that merged art and everyday life, they sought to revive the values of play and authentic desire over routine and systemization.

Revisiting such ideas in the context of contemporary society, I maintain the belief that certain aspects of Situationist theory are more topical than ever. This bimonthly column, The New Situationists, is geared towards an ongoing investigation of these ideas, featuring artists and movements (literal and conceptual) that aim to “counteract the spectacle” in modern terms, interwoven with their/my/our personal experiences of place. The piece above, inspired by my discovery of the poet and artist John Giorno, is a fitting introduction revealing a playful spirit and the embodiment of unfettered renewal.

“Emphasis on experience as a state of flux is on the forefront for many negotiating the cultural realities of late capitalism. Considering the search for meaningful engagement in a society that feels increasingly fragmented, certain aspects of Situationist theory are more topical than ever.”

—Praxis Makes Perfect | “New Situationist City,” April 29, 2013