Albert Bierstadt. Among the Sierra Nevada, California, 1868. Oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

“[W]ilderness is a matter of perception—part of the geography of the mind.”

—Roderick Nash1

The existence of wilderness has been a consistent cultural myth, shaped by experiences that, in some form, have always been mediated by others. Whether it’s the depiction of an imaginary utopian landscape or a carefully constructed trail that frames a particular view, the representation—and even definition—of wilderness has always been subjective.

The Wilderness Act of 1964 was one of the most significant attempts to manifest the myth by establishing a legal definition: “A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Based on this description, sites were chosen (and debated), boundaries were drawn (and debated), and four government agencies (with different goals and financial resources) were appointed to administer the newly protected land. It turns out it takes a lot of human involvement to protect something from human involvement.

“Far from being the one place on earth that stands apart from humanity, [wilderness] is quite profoundly a human creation—indeed, the creation of very particular human cultures at very particular moments in human history.”

—William Cronon2

We’ve always manipulated the world around us, and the more visible our involvement, it seems, the stronger our reaction against it. As urban industrialization grew in the late 1800s, artists like Thomas Moran and Albert Bierstadt gave eastern Americans an alternative vision: sweeping vistas of the frontier, untamed and uninhabited (the people who had lived there for centuries were conveniently omitted). Composed from a mixture of the artists’ direct observations and romantic imaginations, these images depicted a wilderness that had never been seen before and not just because their audiences hadn’t traveled west of the Mississippi. Their works served as propaganda for something that never existed in the first place: untouched wilderness, perfectly lit and carefully composed. Today, the popularity of magazines like Kinfolk have a lot in common with these paintings; both present highly stylized images of natural simplicity, created through complicated means. While we worry about climate change, we gaze at “cabin porn” Tumblrs and Instagram our excursions into nature, also perfectly lit and carefully composed. Typing hashtags on an expensive device to make sure people know we “#liveauthentic,” while carefully filtering images to depict naturalness, underscores the ongoing duality inherent to our relationship with the natural world.

The myths we construct about wilderness are also shaped by how others interpret it for us. Looking at a rock might seem straightforward, but walk into any park and you’ll see signs that make sure we leave with a specific understanding of what that rock really means. When we hike on a trail, our experience is wrapped up with that of the person who designed it— we’re being exposed to the things they value most.

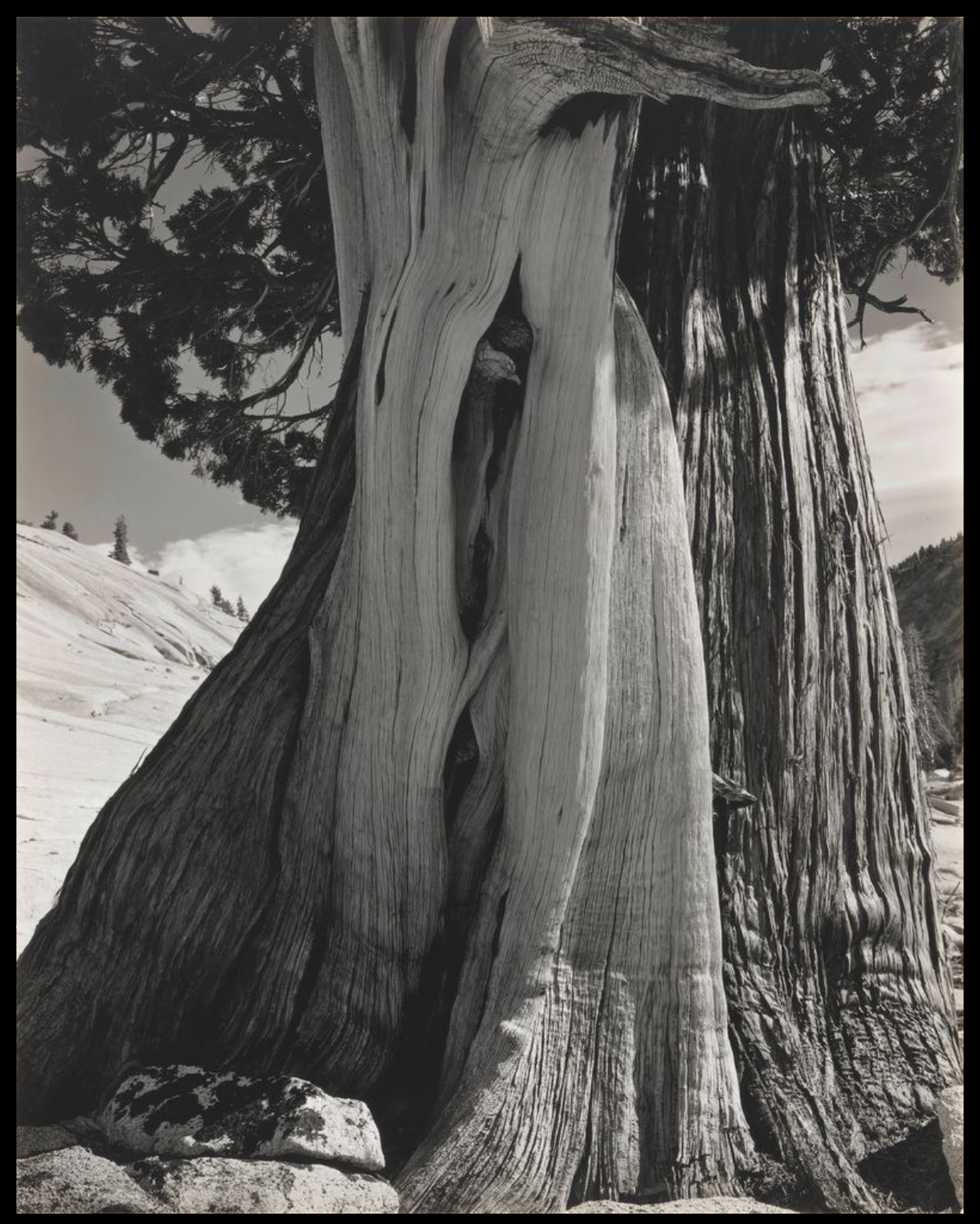

Edward Weston. Juniper, Lake Tenaya, 1937. Gelatin silver print. Collection SFMOMA, Gift of Mrs. Drew Chidester; © 1981. Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“The reason we do interpretation is to help visitors discover and understand the meanings of these sites. For those visitors that already relate the site, interpreters offer opportunities to discover a broader understanding, to see the site with new eyes. The meanings that sites provide can help to inspire and rejuvenate, perhaps leading to an appreciation for the richness and complexity of life.”

—National Park Service3

The interpretive framing of wilderness can also be seen throughout the land-art movement, with artists directly manipulating the landscape to focus viewers’ experiences on a desired impression of a place. As Walter De Maria wrote about his work, The Lighting Field, “The land is not the setting for the work but a part of the work.” De Maria punctuated the New Mexico wilderness with 400 steel poles installed 220 feet apart, shaping how visitors perceive their surroundings based on their positions within or outside the sculpture. Even seemingly direct documentary methods like photography aren’t as straightforward as they seem. For his photographs of Yosemite, Eadweard Muybridge chose specific camera angles and times of day to represent his vision, which differ from the choices made by Edward Weston and by Ansel Adams for their photographs of the same place. Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe physically experienced the perspectives of these photographers by attempting to recreate their views one hundred years later; the merged photographs reveal a nineteenth-century framing of twentieth-century views and, with the medium’s ability to span time, create a mythical portrayal of an otherwise familiar place. Clement Valla examines the subjective nature of another form of seemingly straightforward documentation, Google Earth, from which he collected images that interrupted an otherwise accurate representation of a place—for instance, a ripple in a highway or an upside-down building. Through this process, he realized that Google Earth presents an interpretation based on its processing of the collected data: we see the software’s version of our world, not necessarily what’s actually there.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe. Above Lake Tenaya, Connecting Views from Edward Weston and Eadweard Muybridge, from the Yosemite Project, 2001. Collection SFMOMA, purchase through a gift of Mary and Thomas Field. © Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe.

These interpretations of wilderness only further highlight its intangibility. But while wilderness might not exist in concrete terms, its lack of definition allows us to connect with a place—and an idea—that fulfills a uniquely human need. As Thoreau stated: “We need the tonic of wildness…At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be infinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature…We need to witness our own limits transgressed, and some life pasturing freely where we never wander.”4

1. Roderick Nash, Wilderness and the American Mind (New Haven: Yale, 1967), 333.

2. William Cronon, “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” in Uncommon Ground: Toward Reinventing Nature (New York: W. W. Norton, 1995), 69–90.

3. National Park Service, Interpretive Development Program, “Foundations of Interpretation Curriculum Content Narrative,” March 1, 2007.

4. Henry David Thoreau, quoted by Ernest Partridge, “The Tonic of Wildness,” The Online Gadfly, excerpt from V. A. Sharpe, B. G. Norton, and S. Donnelley, eds., Wolves and Human Communities: Biology, Politics, and Ethics (Washington, DC: Island, 2001).