Dave Kennedy. Studio view of A view to a passageway (in progress), 2015. Photo copies, green tube, wood block, & plastic mounted to Tyvek, 93 x 74 x 6 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

The Seattle artist Dave Kennedy finds familiarity in refuse and abandoned space. The idea of illusion is central to his practice, as he recreates urban scenes by mapping them with his camera. He takes hundreds of detailed photographs, prints them on flimsy copy paper, and stitches them together on clean, white walls. There is a tension, both between mimesis and distortion, and between safety and disarray, as he questions the assumption that photography can perfectly represent the world. While inherently distorted, these representational collages are convincing windows into the scenes he collects and reassembles.

Kennedy’s approach harks back to his origins, growing up in low-income housing in Tacoma, Washington. At first glance, the spaces represented in his works appear empty and lonely, but further viewing reveals they’re full of bustling activity in the form of trash, signage, organic materials, and failing architecture. Sometimes the city leads a double life, and Kennedy highlights these duplicitous moments. Ultimately, his work is a portrait of urban America, a personal inquiry of neglect and ignorance.

Dave Kennedy. A view to a passageway, 2015. Photo copies, green tube, wood block, & plastic mounted to Tyvek, 93 x 74 x 6 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Mark Reamy: How does the idea of illusion enter your work? Can you talk about the relationship between photography and illusion, and between photography and the real world?

Dave Kennedy: I am interested in taking away the blinders that can make someone into a predetermined something. I believe that being a person of color in America involves a process of moving through and adopting from many different cultures. Realistically, to settle on superficial assumptions that define what’s authentically Black or White, or anywhere in between, is virtually impossible. There are as many ways of being as there are people. So I point to layers, and the many ways of seeing an object, as a way to get beneath the skin of things.

Putting a camera up to one’s eye begins the process of manipulating what’s in front of us, to create a representation of what was there. In this way, photography is both documentation and manipulation at the same time. I want to exploit both of those aspects of photography to point to the way we accept the things we see. Creating an image of an image of an image, the work I make ends up appearing in so many ways: real, not real, facsimile. When viewers realize that there’s a trick involved, they take a longer look than usual.

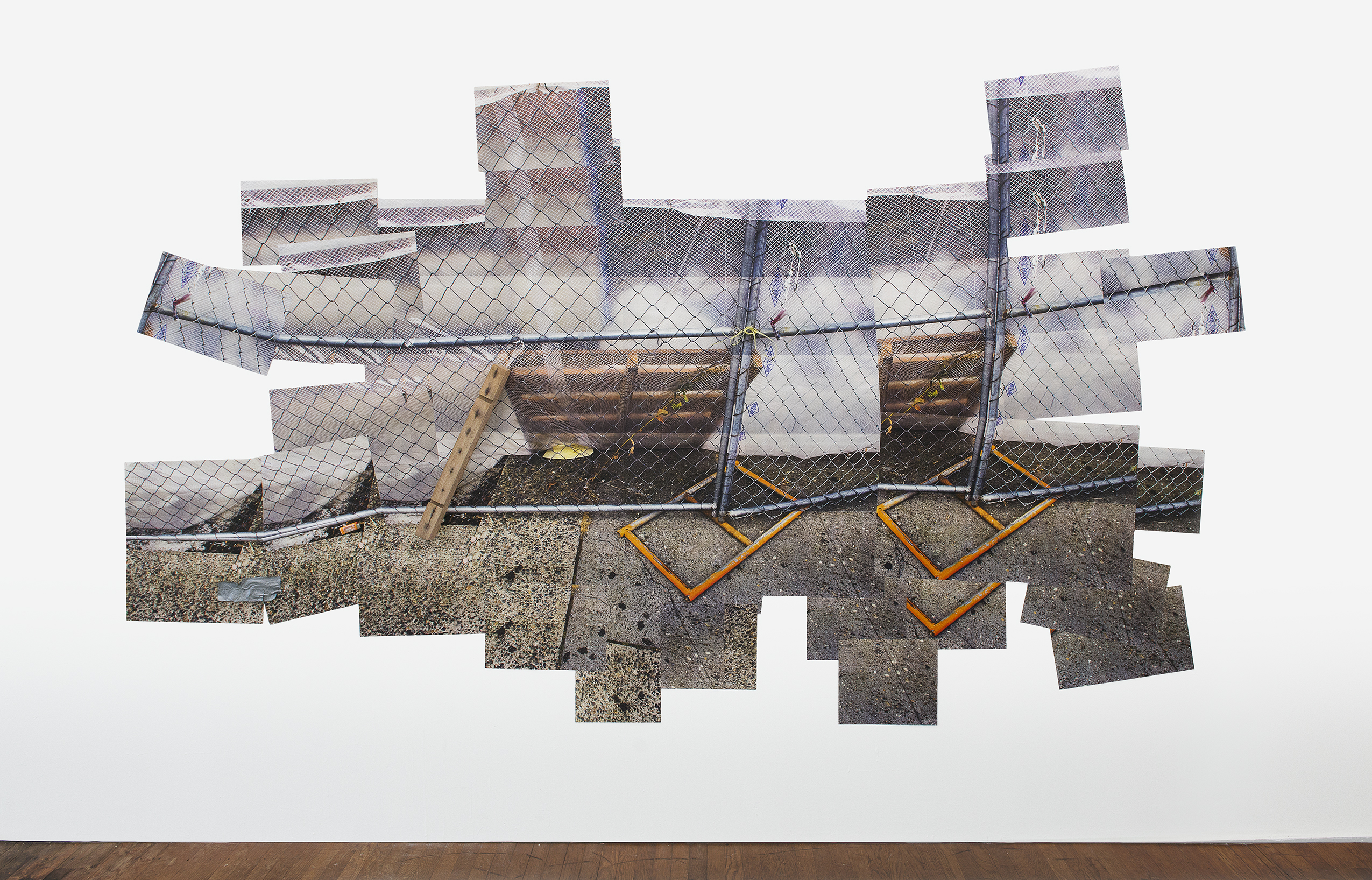

Dave Kennedy. The window and the landscape, 2016. Photo copies, fence stick, orange lighter, duct tape & adhesive mound mounted to Tyvek, 132 x 78 x 4 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

MR: Why do you use cheap photocopy paper? Why do you return some of the objects you photograph to three-dimensional space?

DK: Photography has a problem: it’s too precious and mechanical. The physical medium describes a sole, two-dimensional, framed experience. The work I’m making represents my experiences. Life is not flawless; things don’t always perfectly match up. With its many [image] artifacts, the photocopy seems closer to this [imperfect condition]. I have yet to find a copy machine that can print accurate color consistently from one day to the next, let alone one page to the next. Sometimes there are toner globs that appear on the page. Sometimes the image comes out with streaks. I take whatever the machine gives me on any given day. Adhering the tiled sections together feels like a performance of investigation. The photocopy allows me to physically take apart the image and put it back together. I do this in part because I believe that social constructs are stories that can be taken apart and told differently.

MR: Can you describe your childhood growing up in Tacoma? How does that influence the content of your work?

DK: I grew up in a housing project where there was a lot of racism bred of misunderstanding. Each street seemed to have many ethnicities represented. However, my mother is Italian and Eritrean, and my father is Irish and Native American, so I didn’t look like one [ethnic group] or another. I would walk these multicultural city blocks alone, looking for someone else like me. It was common for people to make assumptions of what I was: Mexican, Samoan, Black. My response to these objectifying guesses is imbedded in my practice and my exploration of an expanded view into unseen subjectivities.