Erin Dunn. Oceanic Dancer, 2016. Still, HD Video. Courtesy of CUE Art Foundation, New York. © Erin Dunn.

Erin Dunn grew up on the Jersey Shore and spent her childhood exploring the Pine Barrens, the vast patch of forest known for misshapen trees and fantastic tales. This odd, little-explored expanse of land, in the middle of a region famous for its turnpikes and boardwalks, deeply influences Dunn’s airbrushed paintings and stop-motion animations, in which the artist mixes the natural with the grotesque to create mythic illusions.

In Dunn’s latest stop-motion animation, Oceanic Dancer, the Pine Barrens are subtly indicated by a background of artificial pine trees. The scenario includes strings of colorful lights, faux flowers, and mounds of sand, representing the contradictory visual worlds of Dunn’s girlhood. The puppets that she animates in this setting capture the fantasy of performance: the ideal of the dancer who can let go of her inhibitions and allow her body to lead. Inspired by the idea of Sigmund Freud’s “oceanic feeling”—in which an infant experiences a oneness with the world before it learns that other people inhabit it—Dunn seeks to express that feeling through motion.

Erin Dunn. Oceanic Dancer, 2016. Still, HD Video. Courtesy of CUE Art Foundation, New York. © Erin Dunn.

A captivating and upbeat tempo anchors the work, which is enhanced by dramatic lightning. It begins with a strange pink bird, dancing on the whimsical stage, its feathers blowing with each twirl. Dunn makes all of her characters by hand; her puppets resemble plastic dolls or, in the bird’s case, feathered Muppets. Oceanic Dancer features female dancers outfitted in eclectic embroidered tops or beaded headpieces, each performing alone on the colorful stage, moving between plié and pirouette. One dancer, her skin a vibrant red, even dances with paper umbrellas in hand, amplifying the theatrics of the performance. Close-ups reveal Dunn’s attention to detail: the puppets’ eyes open and close during particularly expressive moments. Through gesture and song, Oceanic Dancer visualizes the freedom of letting go as a kind of purity.

While this essay was written before Oceanic Dancer was finished, there is little doubt that the work’s momentum between dance, lightning, and sound will continue to grow until it is completed. Judging from the artist’s previous works, particularly the 2012 stop-motion animation, Rapture’s Adagio, Dunn will increase the complexity of these elements to create unpredictable and elaborate expressions full of mesmerizing movement.

Erin Dunn. Oceanic Dancer, 2016. Still, HD Video. Courtesy of CUE Art Foundation, New York. © Erin Dunn.

Dunn’s stop-motion animations are imbued with the artist’s sensibility as a classically trained ballet dancer. She understands the subtleties of movement—the gesture of the hands or the point of a toe—which adds a sophisticated elegance to the aesthetic of her work. She subverts this elegance, however, with grotesque imagery derived from old-time fairytales. Also referring to Surrealist film and painting, she embraces odd, distorted shapes and dense spaces, layering elements on top of one another to create elaborate sets and eccentric characters. Dunn’s works also have a deliberate girlishness to them: the artist is unafraid of the stereotypical pinks and purples, or glitter and sequins often associated with female adolescence. Dunn’s work is thus a complex aesthetic of contradictions. It is at once elegant and kitschy, natural and artificial. Her works are full of illusion and fantasy yet feel relatable and familiar.

While Dunn’s work is certainly in dialogue with a number of contemporary artists who embrace stop-motion animation and the fantasy of its methodology, such as Allison Schulnik and Nathalie Djurberg, her practice more importantly harks back to earlier animators. Stop-motion animation from Eastern Europe, such as the work of the Czech artist Jiří Trnka and his studio, had a clear influence on Dunn’s artistic development. Beginning his career as a set designer, Trnka, like Dunn, came to animation through the stage, merging the tradition of Czech puppet theater with film and maintaining a commitment to the handmade. As an illustrator for tales by the Brothers Grimm, Trnka also took inspiration from myths and children’s stories about love and friendship that were full of strange and frightening details.

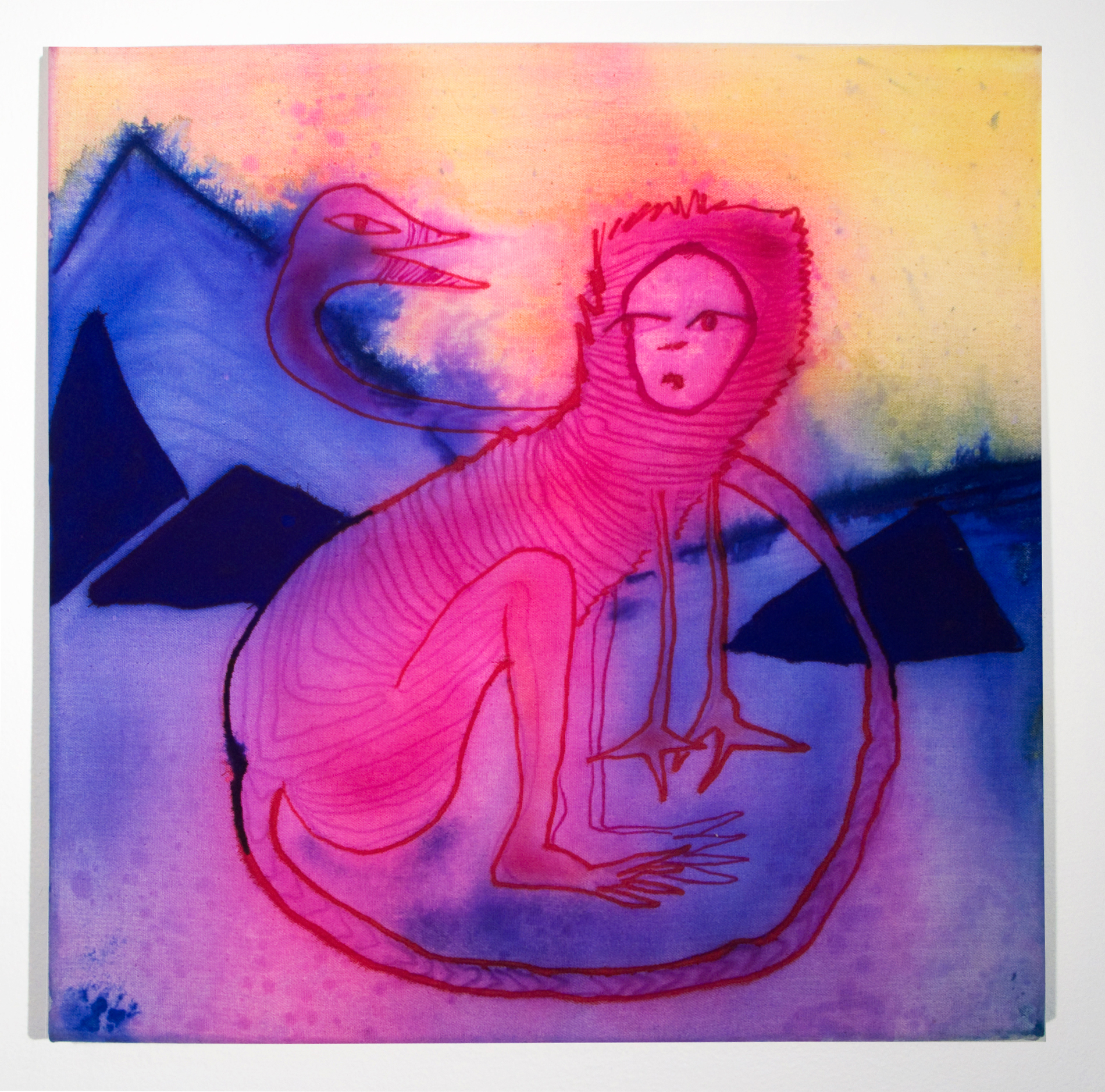

Erin Dunn. Connected, 2016. Watercolor on canvas, 20” x 20”. Courtesy of CUE Art Foundation, New York. © Erin Dunn.

For Dunn, this reference to childhood stories is important. Citing her interest in myths and fairy tales from around the world, she intentionally celebrates the fantasies of youth while reminding us that these stories are very often dark, with their meanings imbedded in the complexities of life. Indeed, as much as Oceanic Dancer speaks of the freedom of letting go, it is also full of nostalgia, particularly the nostalgia for the carefree ethos of adolescence. The work also speaks of desire and the act of looking at the female body. In this way, the artist’s experience of growing up in the sexualized environment of dance, where the body is constantly on display, makes its way into the work, with Dunn inviting viewers to ask: Are the figures dancing for themselves, as if alone in their bedroom? If not, who are they dancing for?

Painting and drawing are also central to Dunn’s practice. In her latest series of watercolors, she airbrushes canvases to create brightly colored portraits of female characters or made-up creatures, some anthropomorphic, others recognizably animal. Though Dunn often exhibits these works apart from the animations, the relationship between her painted characters and sculptural puppets is evident: their odd-shaped bodies and exaggerated, black-lined eyes evoke the same mythical presence. The semi-translucent airbrush aesthetic—referring to the caricaturists and material kitsch of boardwalks on the Jersey Shore—also heightens the sense of fantasy in her work.

Erin Dunn. Spectra, 2016. Watercolor on canvas, 20” x 20”. Courtesy of CUE Art Foundation, New York. © Erin Dunn.

Furthermore, Dunn frequently incorporates painted elements in her animations. Rapture’s Adagio, inspired by Piero Camporesi’s essay “The Prodigious Manna,” begins with stunning, hypnotic abstractions overlaid with film sequences of beaches and forests. The abstractions evoke the hallucinatory visions of the main character, Chiara da Montefalco, a medieval nun whose heart (as the story goes) was pierced by the Cross, giving her lifelong hallucinations and pain. These abstractions first appear as colorful dots floating in the center of the work, animated to resemble fireworks or kaleidoscope patterns that appear and disappear as the film progresses. Like her puppets, Dunn’s painted abstractions move and change with the rhythm of the work—at first mimicking the slow, haunting tempo of an accompanying male voice and later simulating the pulse of a heartbeat—offering a new, animated take on optical illusion.

The eleven-minute-long animation leads the viewer through moments in Chiara’s life as a nun, and the abstract animations become the background of a more formal setting for the puppets’ performance. From ritual acts to the dissection of a human heart, depictions of movement—including an impressive synchronized duet—remain the core of the animation. Moving from animated illusion to concrete reality, the work culminates with Sister Chiara, her hallucinations and chest pains gone, dancing naked on an actual beach, with her long dark hair cascading down her back—representing, once again, the freedom of letting go. Both Rapture’s Adagio and Oceanic Dancer underscore the deep sense of spirituality that runs through Dunn’s animations. Whether pulling from the performance of Catholic rituals or reminding us that dance can be a spiritual exercise, Dunn shows how the body is central to systems of belief.

Erin Dunn. Rapture’s Adagio, 2012. Still, HD Video. Courtesy of CUE Art Foundation, New York. © Erin Dunn.

Following in Trnka’s tradition, Dunn imbues her training as an animator with her sensibility as a craftswoman. Producing nearly all of the components that make up her animations, from painted backdrops and costumes to lightning and sound, Dunn enjoys the process of making; the hot-glue gun is just as important as the camera. She is committed as much to knitting and sewing as to painting and animation, and actively employs new techniques and processes. For instance, for Oceanic Dancer, she learned from YouTube tutorials how to make anatomically correct dolls from silicone molds. Embracing the labor of art, Dunn emphasizes the time and energy involved in the production of stop-motion animations.

In this process, Dunn continuously blurs reality and illusion. She explains, “I am tricking the audience to enter a world, when really it is just sand on my table.”1 Indeed, throughout her work, she invites us to consider the contemporary place of fantasy, asking what reality and illusion are. What appears to be a dancer seamlessly moving through space is merely a puppet posed in each graceful arc or twirl. The real movement comes from the artist herself, invisible to the viewer’s eyes, slowly orchestrating the entire fantasy behind the scenes.

1. Quote from Dunn during a studio visit on February 29, 2016, Brooklyn, NY.

Editor’s note: This essay was written by the ART21/CUE Writer-in-Residence in conjunction with the exhibition Erin Dunn: Oceanic Dancer, curated by Rujeko Hockley and on view at CUE Art Foundation June 4 – July 9, 2016. This text is included in the free exhibition catalogue, which is available at CUE and online here.

The ART21 + CUE Writing Fellowship provides each writer with a mentor—an established art critic appointed by the International Association of Art Critics USA Mentoring Committee. Rachel Heidenry worked with the art critic, commentator, and filmmaker Amei Wallach.