The year 2014 brought many commemorations in Germany, but one historical turning point was met without significant fanfare: at the Berlin Conference, one hundred thirty years earlier, Europe’s imperial powers met in the capital city to slice up the African continent. The conference marked Germany’s emergence as a colonial heavyweight, a role that lasted until the end of World War I, and has gone largely unacknowledged even though it resulted in more than three hundred thousand deaths.

How does this historical omission affect our understanding of Germany’s present as it publicly grapples with the influx of people fleeing war and a deeply rooted rhetoric of otherness? Without awareness of this shameful event, it’s harder to contextualize current battles against systemic racism and easier to relegate hate speech and xenophobia to the legacy of National Socialism or fringe right-wing movements.

Colonial Neighbors, a project at Savvy Contemporary—a multifunctional art space, community hub, and archive in Berlin, initiated in 2009—seeks to uncloak Germany’s role as an occupier through an expanding collection of donated and acquired objects. When I visited, Anna Jäger, one of the artist-members, showed me an early-twentieth-century scrapbook of photos of taken by a German soldier of a colony in Cameroon. The book was found in the attic of a relative of Savvy’s founder, Dr. Bonaventure Ndikung. At the edges of the photos, viewers can detect hints of the violence and destruction that were hallmarks of what is known as the Scramble for Africa. Also in the Savvy archive are board games, puzzles, ivory necklaces, and mid-century books that instruct German schoolchildren about “exotic” African cultures. Jäger insists that Colonial Neighbors is definitely not about fetishizing objects and instead focuses on these historical fragments so that we can arrive at a more complete collective memory, one that will allow us to reckon with our present.

Gerda Steiner and Jörg Lenzlinder. Aus dem Urmeer zwischen Afrika und Europa, 2013. Photo: Elsa Westreicher.

Savvy Contemporary is situated in a preserved crematorium built in 1911, itself a historically significant site that may have served darker purposes during the war. The sprawling complex lies in the Wedding district of northern Berlin, where, at the turn of the twentieth century, the African Quarter was the proposed site of a human zoo showcasing so-called primitives from Germany’s colonies. There are streets named Togo and Cameroon, and several still shamefully bear the names of famous German colonialists, like Adolf Lüderitz.

The historical complexities of Savvy’s physical location are echoed by its heady and nuanced exhibition program, which centers on thematic concerns rather than conventional notions of Western and non-Western art. With each exhibition, curators and artists from Africa, South America, Asia, or Australia are invited to engage in a critical dialogue with other art professionals from Europe and North America.

What is the role—and responsibility—of institutions and art spaces dealing with history to disrupt the presumptive Western, male narrative? Should it tell a broader, arguably messier story arc? The urgency of projects like Colonial Neighbors questions the museum as a sacred site of education and purported neutrality. Increasing numbers of survey shows explore issues of race, sexuality, overlooked movements, and outsider artists, but in what ways do these special exhibitions mimic and genuflect toward broader colonialist leanings—by briefly showcasing a collection of oddities that have been quickly erected to support a historical framework already in place?

Exhibition view of Dierk Schmidt – Broken Windows 6.3 at KOW, Berlin, 2016. Photo courtesy of Ladislav Zajac and KOW, Berlin.

In Savvy’s last exhibition, What the Tortoise Murmurs to Achilles: On Laziness, Economy of Time, and Productivity, the Swiss artist duo Gerda Steiner and Jörg Lenzlinger appropriated museum tactics to critique institutional adherence to a historical timeline. In the work Aus dem Urmeer zwischen Afrika und Europa (2013), they arranged a number of objects with a label—“from the ancient seas between Europe and Africa”—such as items resembling oceanic fossils alongside rubber shoe soles. This positioning subverted the organizing principles of age, worth, and institutional validation that comes with Natural History Museum modes of presentation.

For a recent exhibition at KOW in Berlin, Dirk Schmidt’s Broken Windows 6.3 literally collapsed the tools of colonialist oppression with those of bureaucracy. In this work, Schmidt referred to Germany’s imperialist past through a series of cracked and shattered glass vitrines atop pedestals. The vitrines were devoid of objects, and the outsides were scratched with mechanical notes that implied theft or cultural appropriation, “emptying” our conception of the museum as an unsullied purveyor of universal truths.

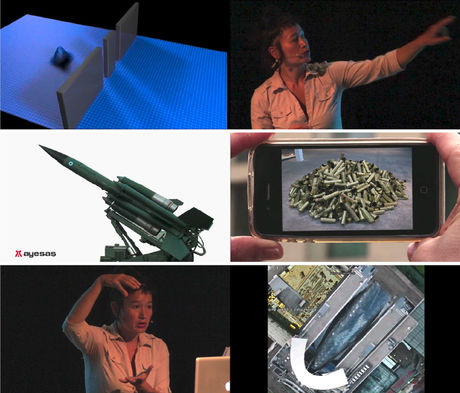

Earlier in the year, the artist Hito Steyerl’s exhibition at KOW explored the museum as a nonsacred site, one inexorably enmeshed with the military industrial complex. In a video of her lecture, Is The Museum a Battlefield? (2013), Steyerl traced the origins of the ammunition casings used to kill her childhood friend, Andrea Wolf, a fighter for the Kurdish Workers’ Party, who was executed in Turkey in 1998. Following the detritus, Steyerl was led to the corporate lobbies of weapons manufacturers, many of which are designed by Frank Gehry and house works by contemporary artists like Anish Kapoor and, to Steyerl’s horror, herself. She eventually followed the rocket shells to Lockheed Martin, a company that sponsors both the Istanbul Biennial, where Steyerl gave her lecture, and her exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago.

In another video lecture, Duty-Free Art (2015), Steyerl demonstrates how the Louvre Museum, the British Museum, and the architect Rem Koolhaas became involved with the murderous Assad regime in Syria, helping to plan and design a future museum in Damascus. Steyerl patiently points us to the dark, moneyed undercurrents that steer the art world and its interests while she aptly acknowledges her complicity in it.

In a subsequent video lecture for the 2012 Creative Time Summit, Steyerl describes the museum as a historical site of revolution and upheaval, referring to the Hermitage Museum’s starring role in the October Revolution of 1917 and stating defiantly that we need to “storm the museum again.”1 What seems especially true now is that museums have not been spared from a collective loss of institutional faith. By questioning the transparency and accountability of our institutional narratives, artists and initiatives like Steyerl and Savvy Contemporary bring us one step closer to rupturing the illusion of transparency and neutrality encased in glass and obscured by pedestals.

1. Paul Schmelzer, “Hito Steyerl: Is the Museum a Battlefield?” Walker Art Center blog.