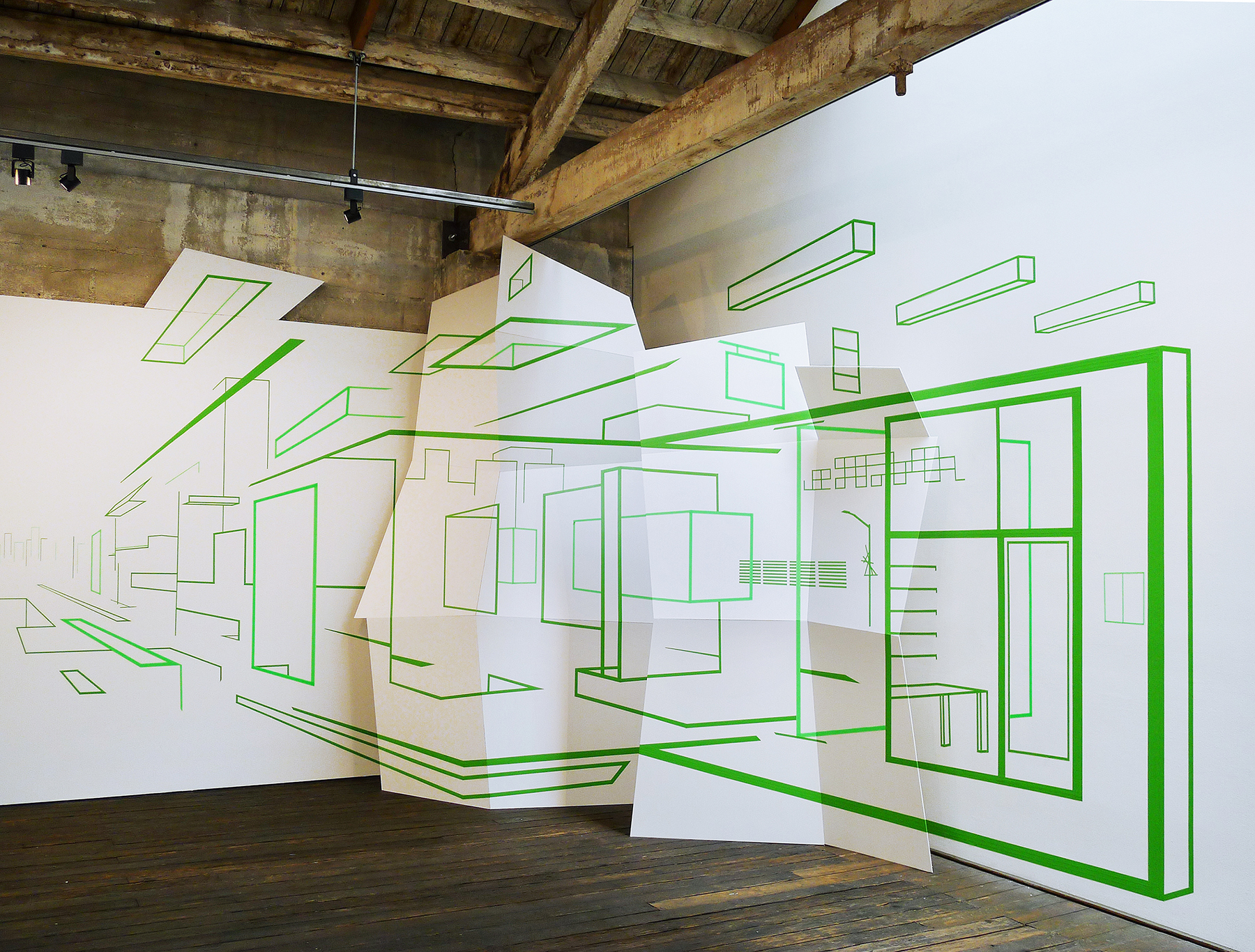

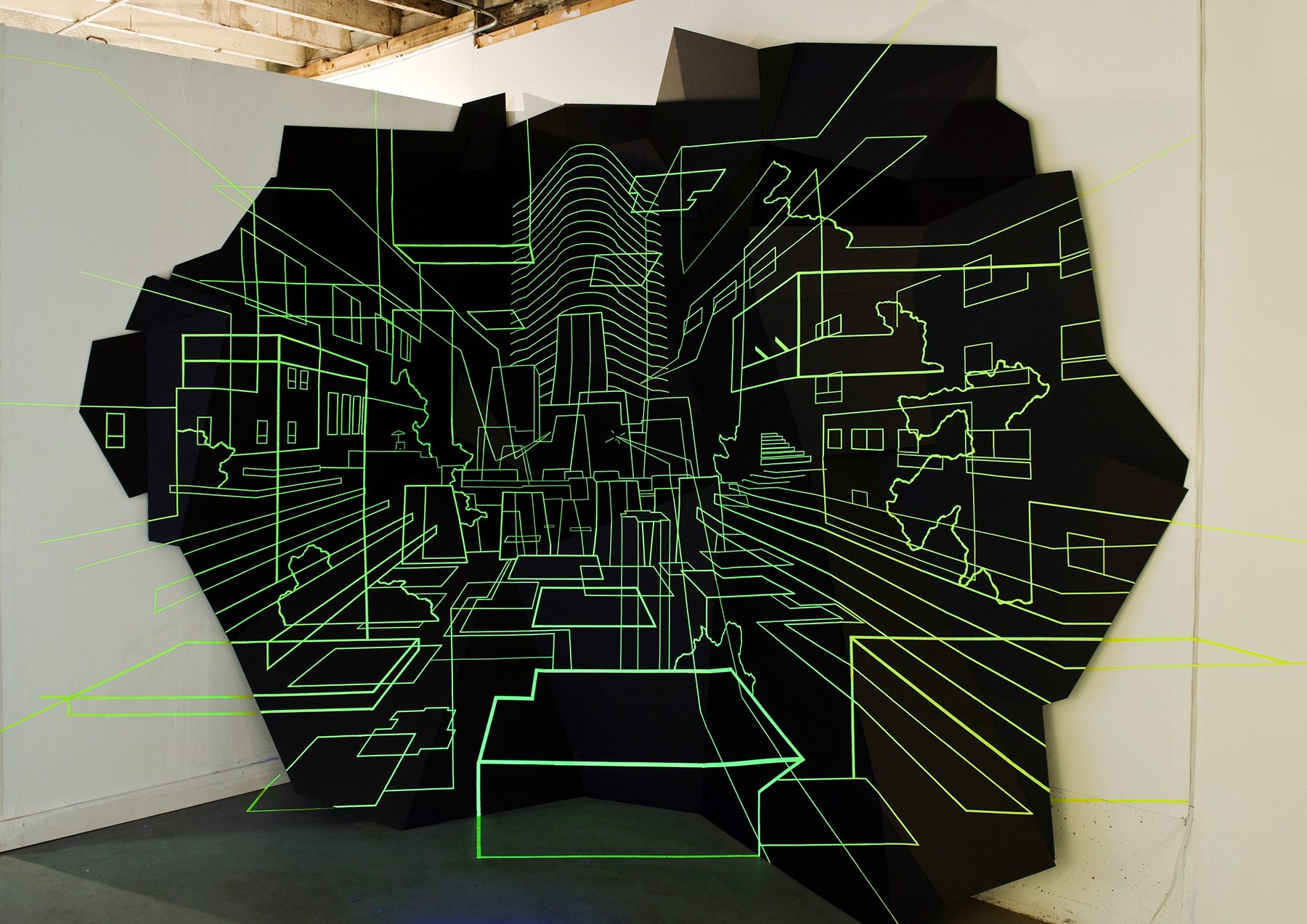

1+1=1

At Disjecta Contemporary Art Center in Portland, Oregon. The work rests in a corner and bends with viewer movement.

Perception in relation to time is what connects my early work, focused on the digital manipulation of imagery and video, to my current installation works. Video manipulates time and gives the viewer a new sense of it, yet often the viewer is only passively engaged. Two-dimensional work may not make use of time in the same way, and may be a more passive experience than video, but my approach incorporates kinetic movement as an important aspect of viewing.

I do not think all viewers will see my work as I intend. Often my work has prescribed viewing points, sweet spots from which the viewer can experience perspectival effects. With my work, when the viewer finds a certain sight line, forms will align, connections are made, and the drawing seems to complete itself. Finding this spot can be awkward, but I find that the most powerful aspect of the work. To walk around the work is to activate it, to animate it, to make it materialize. There is usually a moment at which the viewer cannot yet align the work but is on the cusp, creating a tension, excited to complete the image. After finding the viewing point, the viewer eventually leaves, and the work breaks apart, or warps, or skews in various directions.

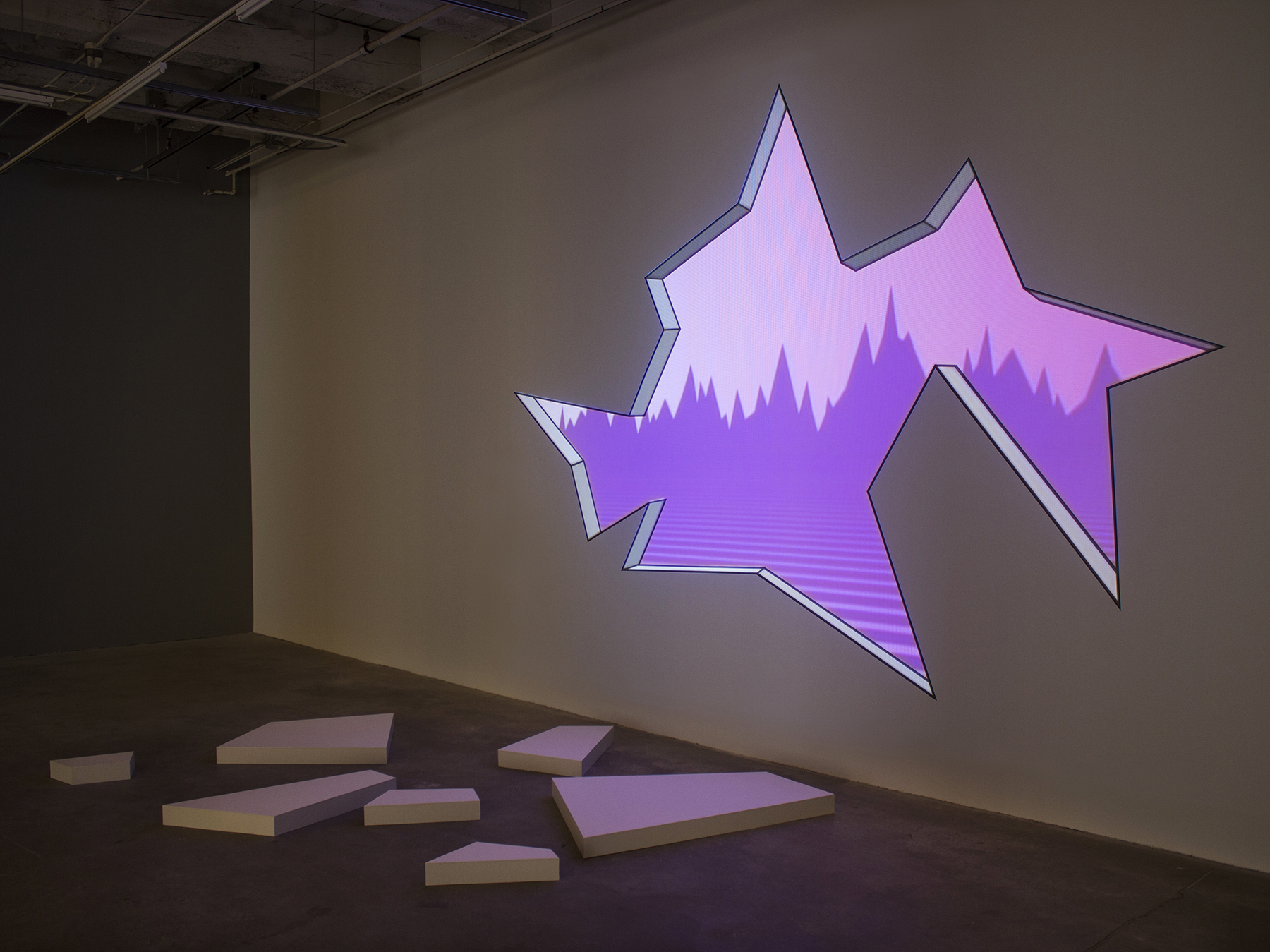

Breakthrough Moment

At Bemis Center for Contemporary Art in Omaha, Nebraska. This projection on vinyl and latex drawing introduced a viewing angle offset from the work, so the alignment and effect of depth is awkward at most other viewing positions. Foam core constructions populate the floor.

Illusions can be very complex or very simple. I think of my work as minimalist for its limited formal elements of line and plane. But I also limit my materials; I often choose items that do just enough visual work yet reveal their nature up close. Common masking tape, drywall, sign vinyl, foam core, and nylon string all serve as perceptual materials in my work. I want the illusion to be convincing, yet I want the viewer to acknowledge the illusion. My aim is to get the greatest visual effect from economical forms and materials and simple means, a humble illusion disguised as a grandiose gesture.

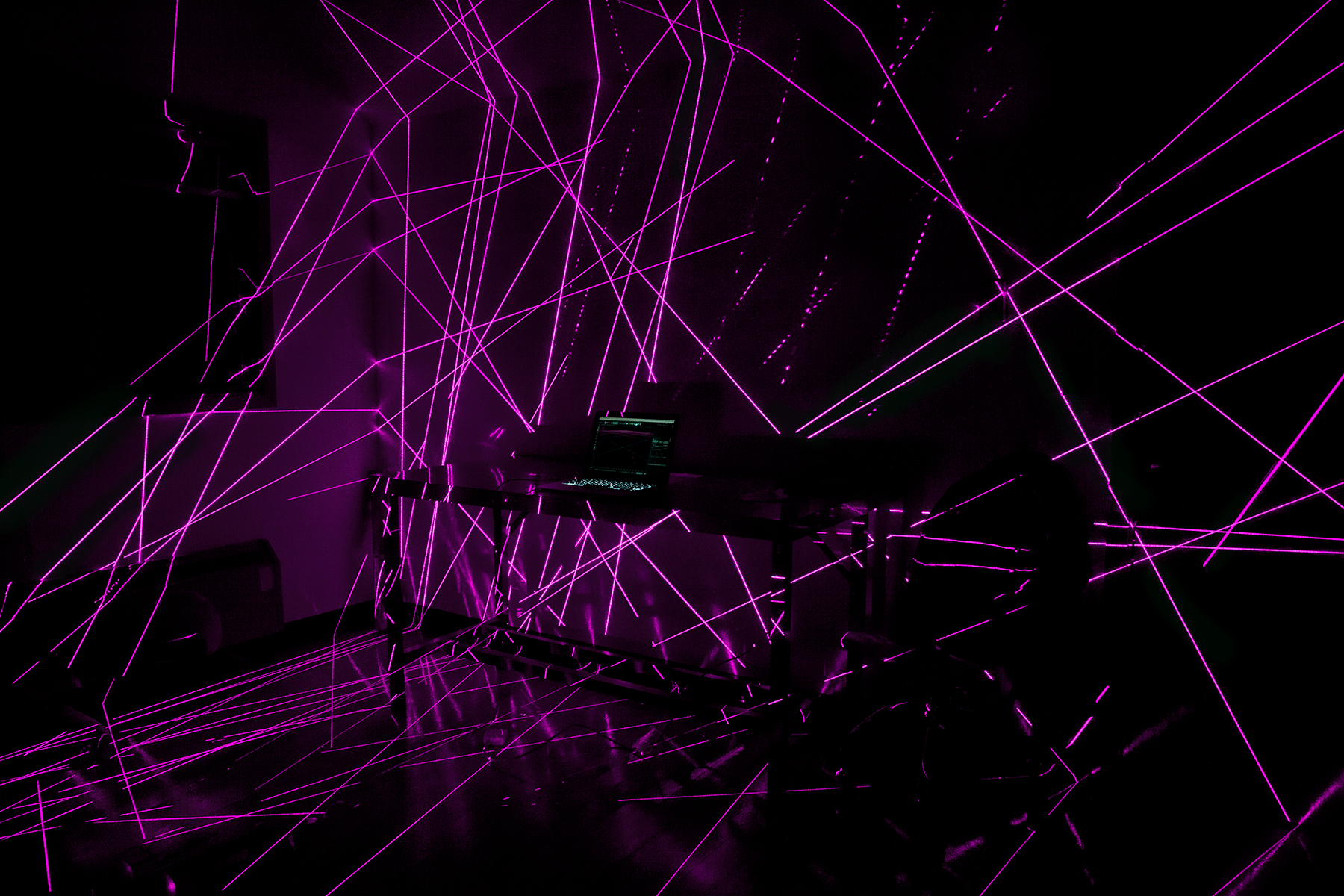

My work has manifested as video, wall drawings, photographic experiments with lasers, thousands of pieces of hanging string, basic projection mapping, and more. Recently I returned to video with a conceptual goal of simulating computer graphics. My work reads as a digital composition yet is purely analog in capture; this intention, for the work to simulate what it is not, becomes a lure for the viewer to look at the work. The illusion is less about how the visual result is experienced and more about leading to a discovery of the process.

Axis Index

At Suyama Space in Seattle, Washington. This work introduced extreme planar disruptions to a 360° forced perspective drawing with a very precise viewing position in the center of the room.

Functioning in a similar way are my light wall drawings, which consist of a projection mapped to a precise vinyl-and-acrylic drawing on the wall. They have an obviously low-fi quality when seen up close, where the precision of the projector breaks down and the pixels become visible. Next to the crisp vinyl line, the projection sinks into space, like a hole in the wall, slightly out of focus. Yet when viewed from further away, at the prescribed, anamorphic angle of forty-five degrees, the works have an uncanny realness, though the disparate materials evade identification.

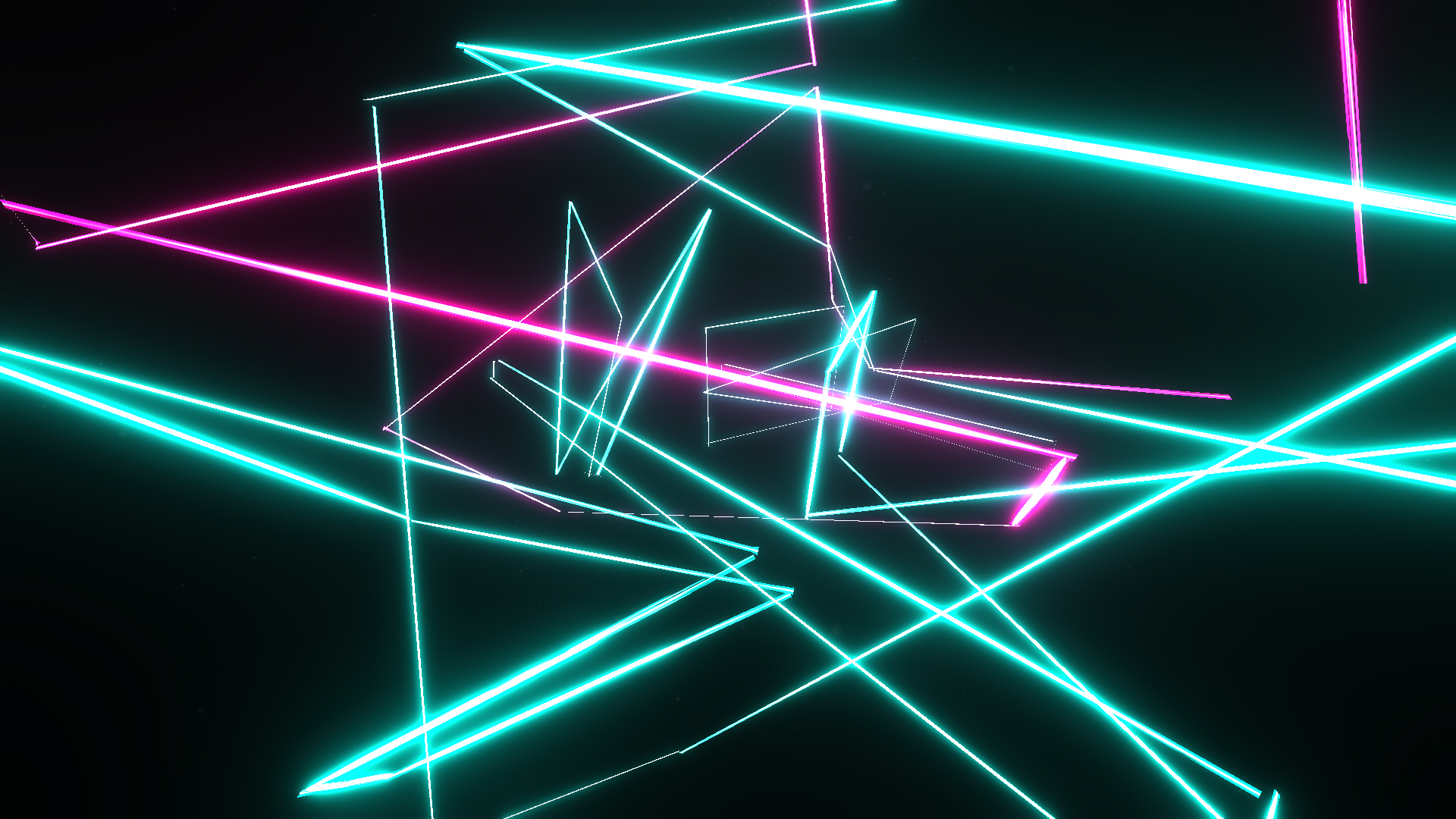

I just finished developing a solo exhibition to be presented in virtual reality. The work will use newly released technology, which will entail a room-size digital drawing, created in the virtual space by hand. Though the materials are no longer economical, the visual elements are stripped to the essentials: lines and planes in space, arranged to entice the viewer’s movements within it. Viewers can walk through the drawings, using their points of view to navigate a floating sculptural experience. This new medium seems perfect for my work. It produces what I have been searching for: making visible what does not exist.

Ex Image

A new series of work, this piece talks about extrusion of images into space. The white painted marks on individual strings align to create an illusionistic form from one view only.

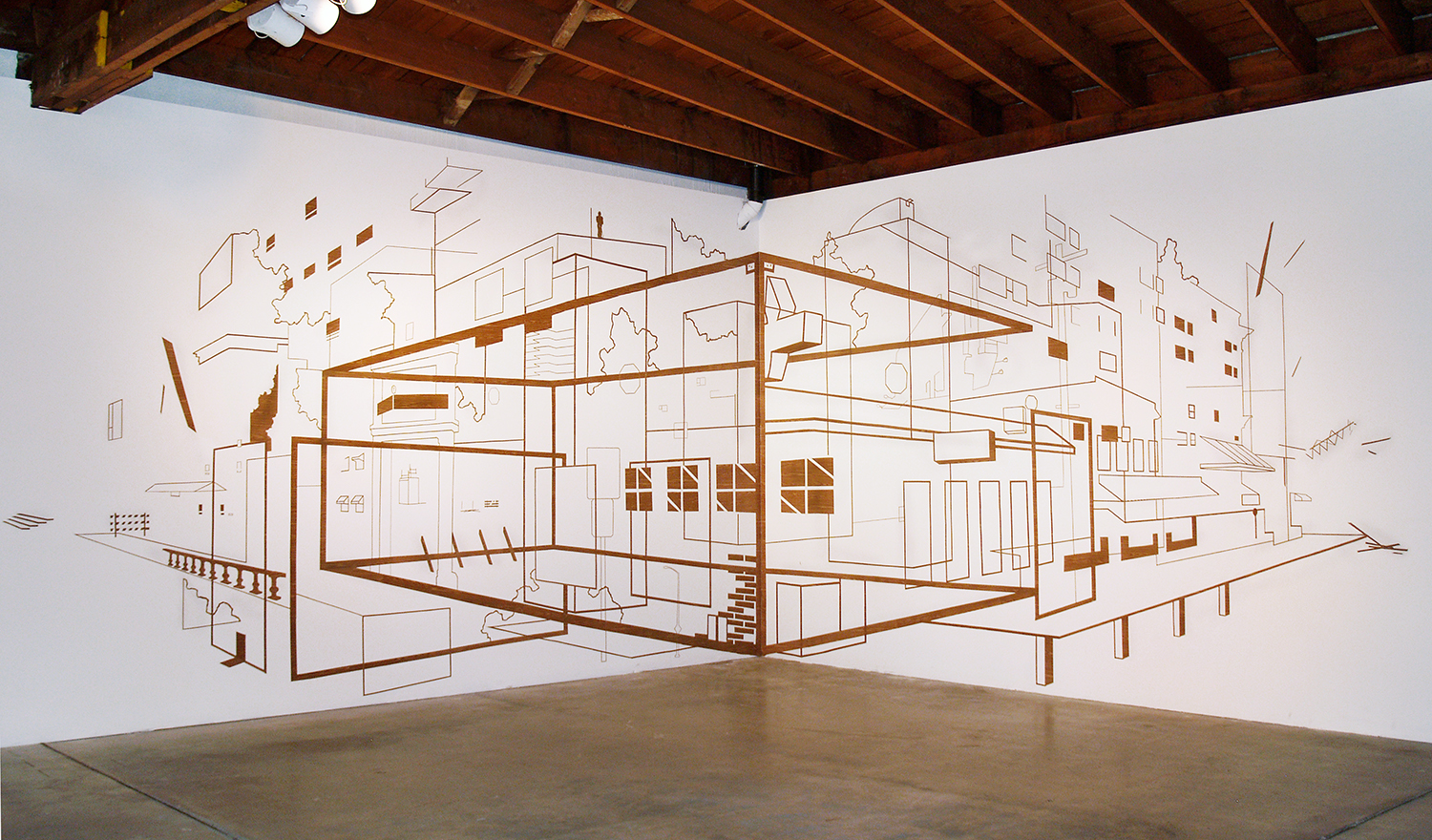

Masterplexed

At Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon. The work is entirely made of drywall, 2×4’s, house paint and sign vinyl. A very simple construction process yet the drawing aims to destabilize that pattern of building.

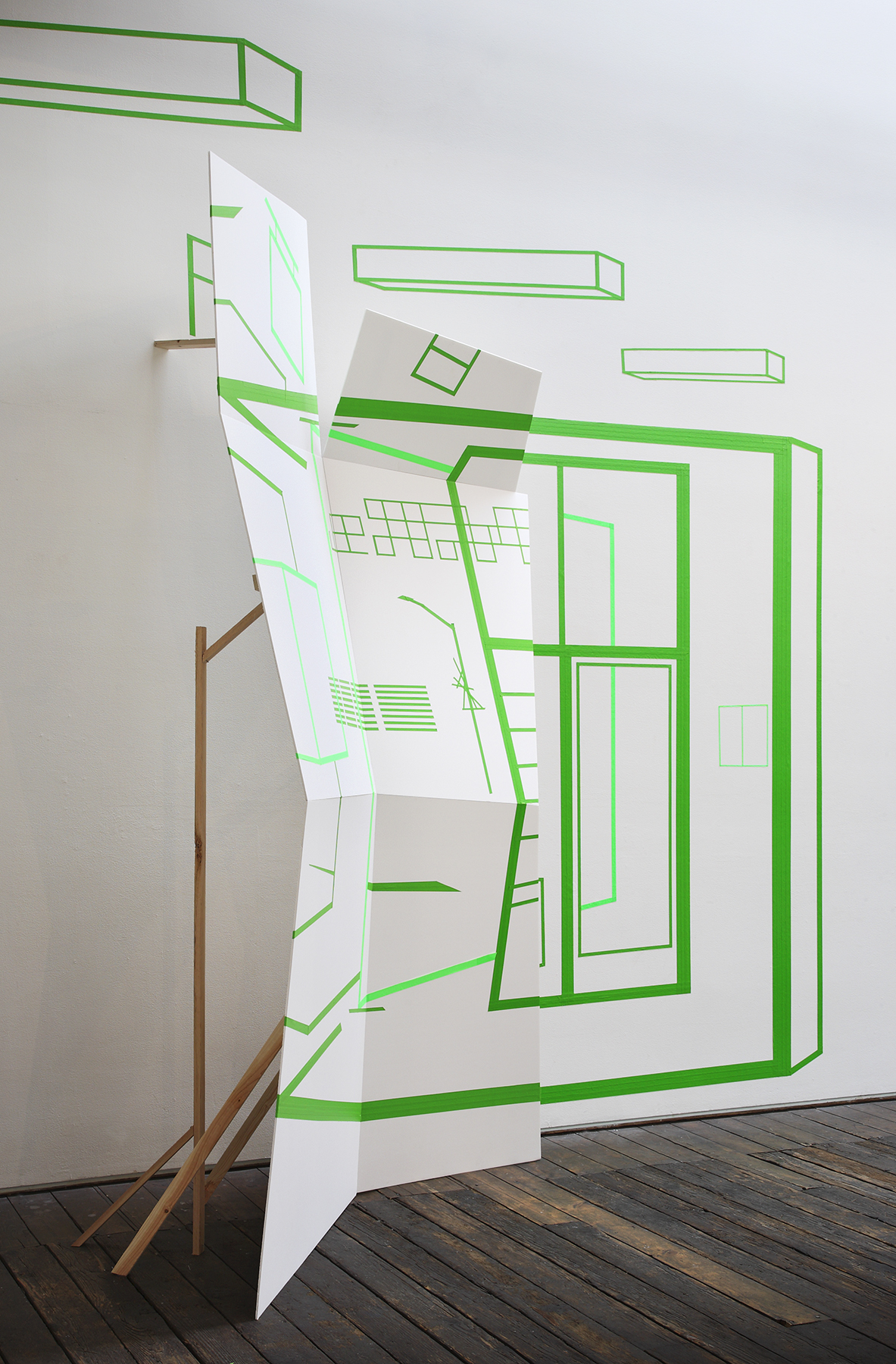

Fortress

A variable depth foam core structure was constructed as a dynamic surface for this forced perspective drawing to be created.

Virtual Reality tests

This is a snapshot through the viewfinder of the virtual reality headset. Using software like Google Tilt Brush allows drawing in real time in 3D space.

Laser Scans

Using multiple consumer laser levels, I create video and photographs of laser exposed architectures. In complete darkness, the individual line of the laser is profoundly informative, despite its limited area of exposure of the site.

Damien Gilley’s work is currently on view in the solo exhibition Specular, at Hap Gallery in Portland, Oregon June 2-July 9, 2016.