Liz Nielsen. Ring of Runes, 2016. Analog Chromogenic Photo, Unique. Printed on FujiFlex. 39 7/16 x 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Danziger Gallery, SOCO Gallery.

Inside Liz Nielsen’s studio, my gaze floated across a large wall filled with chromogenic abstractions in various sizes. Amid the brightly colored totems and constructed landscapes, the Brooklyn-based photographer shared a bedtime story told by her mother when Nielsen was a little girl:

My mom used to sit with me before I fell asleep. I didn’t like the dark nor going to bed, so she made up these nice mental exercises for me to do. Instead of counting sheep, she would say, “Let’s go into the swimming pool and fill it up with all kinds of underwater colored lights,” and I would imagine us there together. It was calming.1

Though it’s a lightly made reference, related threads to the story and its influence run through Nielsen’s life and work. The artist continues to establish her place in the tradition of cameraless photography, most recently illustrated in her solo exhibition with Danziger Gallery. Working in an analog color darkroom and replacing traditional negatives with hand-cut collages of colored gels, Nielsen exposes chromogenic paper to controlled light to create her distinctive abstractions. As she explains, “The final outcomes are preplanned with strong intention and formally composed, yet because I’m working with light, they always have some surprises. The light bleeds and spills and doesn’t want to be contained.” The concept of exposure and its transformative effects also has a more esoteric connection to Nielsen’s work as a gallerist and curator in a series of collaborative projects with her partner, Carolina Wheat. Their most recent project sheds light on the power of vulnerability.

In 2008, Nielsen founded the Swimming Pool Project Space in Chicago. The original mission of the project, embodied in an intimate storefront gallery with a signature blue floor, was to inspire conversation and play in relation to art: a platform for the exchange of ideas, where emerging artists, curators, writers, and performers could meet and connect. Soon after, Nielsen and Wheat joined forces as collaborators and co-curators at the gallery known affectionately as “The Pool.” Over the course of a few years, the project hosted about thirty exhibitions and participated in a handful of art fairs, embracing an experimental approach: events included a dog-fashion show on a catwalk, an environmental Room-A Loom installed for public weaving, and the Living Room exhibition, created in response to a single piece of furniture (specifically, a blue brocade sectional sofa from the 1970s). A job opportunity for Wheat brought the couple to New York in 2011, and both were soon balancing full-time jobs, raising a family, and art careers.

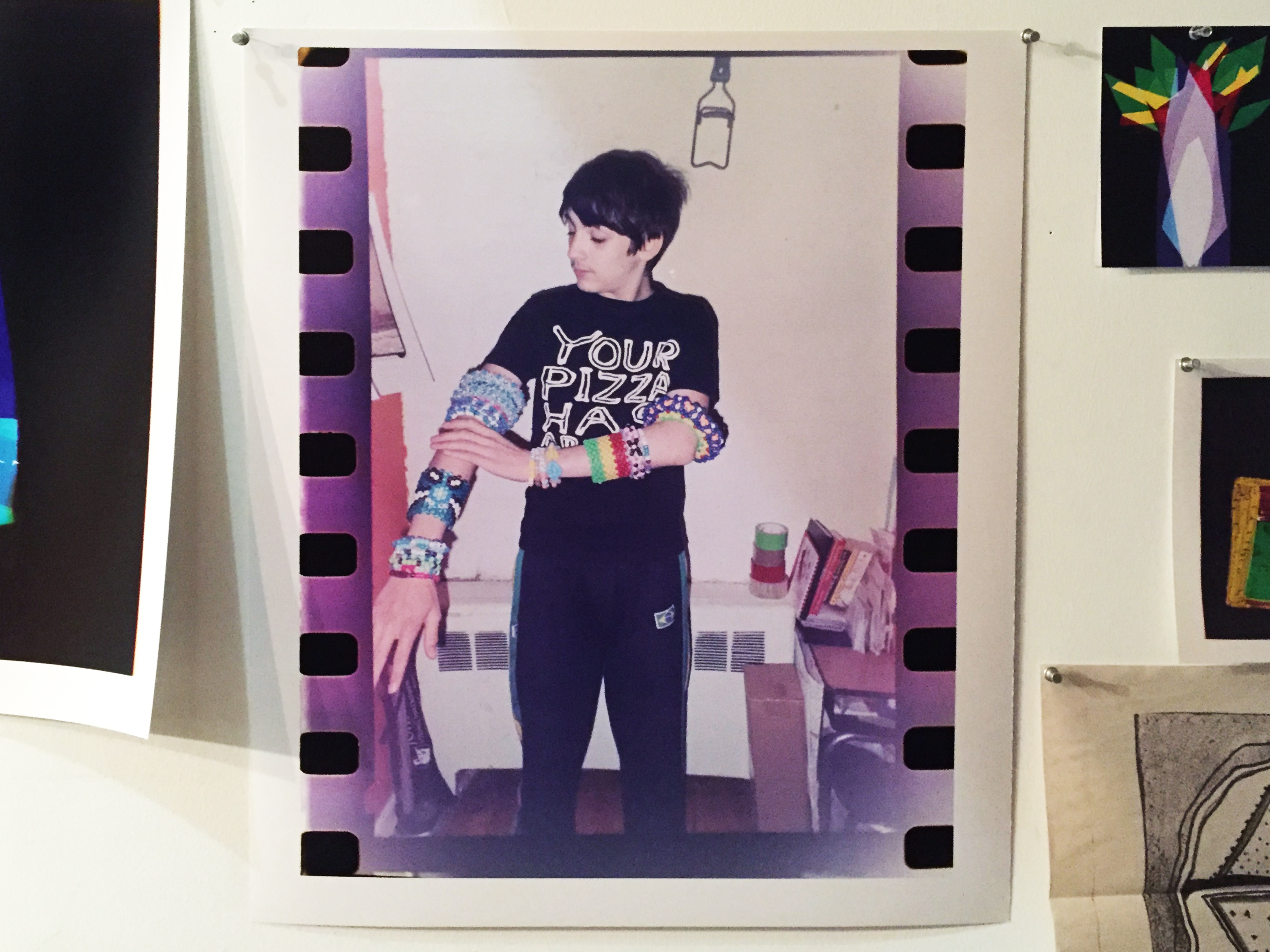

In early 2014, their lives tragically turned when their sixteen-year-old son Elijah took his life. Described as a fiercely independent and extremely charismatic force, Elijah also had a generous and playful spirit. He loved to laugh and bring people together. Skateboarding and video games were interests matched by his budding investigation of Buddhist philosophy and meditation. In addition, he was a talented violinist and dancer who could move effortlessly between Bach and hip-hop. Wheat shared that before he could even talk, Elijah would hum to music with perfect pitch. Busking at street festivals and in New York City subway stations, he loved to make people smile and feel relaxed with his dancing and music. With strong ideas about equality and justice formed at an early age, Wheat knew her son as a deeply empathetic soul who truly felt the weight of the world.

As Wheat and Nielsen tried to come to terms with their son’s passing, they discovered the true strength of their community. “We felt supported, lifted, completely carried by our friends. They held our broken hearts together for us,” said Nielsen. She spoke of those who went above and beyond: friends who “slept at our house, let us sleep at theirs, embraced us while we cried, opened their homes to us, fed us, and took some of the weight away.” Nielsen continued:

The empathy and generosity that we came to know from our group of friends is unparalleled by any other experience in our lives. Suicide is one of the most tragic ways to die and it is almost impossible to accept. Sometimes it feels like an accident and sometimes you can’t help but blame yourself for what you did or did not do. There are so many unanswered questions. It is so difficult to know that someone who you love so much didn’t know how much he was loved.

The following year, in 2015, they established Elijah Wheat Showroom (EWS), to continue with a deeper sense of mission some of the ideas they explored in Chicago. Named after their late son, the gallery honors his spirit of “creative insight, righteous vision, and stylistic voice for trendsetting.” Combating the stigma of suicide and encouraging openness about a challenging topic, they also seek to keep Elijah’s name alive in a positive light. As Nielsen explained, “People say that you die two deaths: the first when your physical body dies and the second when someone utters your name for the last time. We want to keep Elijah’s spirit alive every day by saying his name over and over.”

EWS now thrives as a curatorial project that allows Nielsen and Wheat to be involved with community organizing while sharing political and artistic voices in varied settings. They are, in a sense, continuing to gather those colored lights. Programming at their Bushwick gallery is scheduled to resume in the fall of 2016, and they will be showcasing videos and paintings by Lauren Gregory at the Satellite Art Fair at Art Basel Miami in December. Meanwhile, their most recent exhibition, Transaction, was on view at the Knockdown Center in Queens through July 2016.

Transaction features personal artifacts contributed by twenty-three artists and explores the energy of beloved objects from a personal landscape in a gallery setting. The unique installation of suspended objects at the Knockdown Center—a 50,000-square-foot former door factory recently celebrated by Jerry Saltz as a breathtaking experience—provides ample room for viewers to consider each object in a space that engenders reverence. None of the work is for sale; the value lies in the willingness of the artists to share and the viewers to contemplate in an alternative way.

The concept of the exhibition recalls a parting story about one of the prints on the wall of Nielsen’s studio:

That piece…I don’t know exactly how it happened, but somehow I left the negative on top of the paper—probably because electrons kept it there. So, when I sent the paper through the machine, I couldn’t find the negative, and I thought it fell on the floor. It is pitch black inside the color darkroom, so I really didn’t know where it was. I was paranoid because if you actually send something other than paper through the chemical tanks in the machine, it is likely to break or damage the processor. But the negative came out of the machine on top of the paper, and the image had still developed. Whether or not the piece is fixed is another story, but it seems to have held its color. In any case, this photograph is a personal one and not for sale. The image is a druid, a spiritual leader that one would follow. I imagine—I know—it is a manifestation of Elijah.

1. Unless otherwise noted, all quotes by Nielsen and Wheat are from a conversation with the author on June 7th, 2016 in Nielsen’s Bushwick studio.

Elijah Wheat Showroom’s upcoming exhibition is organized by the artist-run collective ZVX, and features works by Brett Burton, Morgan Ersery, Chris Grady, and Monica L. Bernal. WIDE OPEN SOURCES runs August 5–15, 2016. An opening reception is being held in the Bushwick space at 1196 Myrtle, on Friday, August 5th from 7-10pm.