Kerry James Marshall. Untitled (Painter), 2009. Acrylic on PVC panel, 44 5/8 × 43 1/8 × 3 7/8 in. (113.3 × 109.5 × 9.8 cm). Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Katherine S. Schamberg by exchange, 2009.15 © Kerry James Marshall Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

Kerry James Marshall’s popularity is in step with his unmatched abilities in figurative painting. The title of his recently opened and largest-ever exhibition declares his relationship to the medium as none other than Mastry. Holding court in the heavy, Brutalist galleries of the Met Breuer in a way few others could, Marshall’s enormous, richly detailed canvases project visions of beautiful Blackness from the reaches of history into the twenty-first century. They are some of the most exquisite and adored paintings of the past few decades.

It is surprising, then, that some of the stranger, lesser known, and marginal aspects of the Chicago native’s practice make a greater impact. Curated with characteristic rigor by Helen Molesworth, Mastry takes the viewer from the early days of Marshall’s career as a student in Los Angeles and an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in the 1980s to his towering status at the forefront of a contemporary return to figurative painting and of a generation of successful African American artists engaged explicitly with race and identity politics. Following the arc of his evolving practice, as presented by the exhibition, one sees Marshall working through an overtly political form of history painting to a more distilled mode of anonymous, intimate portraiture that often literally sparkles in its sequined detail. One also sees adjacent projects and unresolved experiments that have contributed from behind the scenes to Marshall’s signature practice.

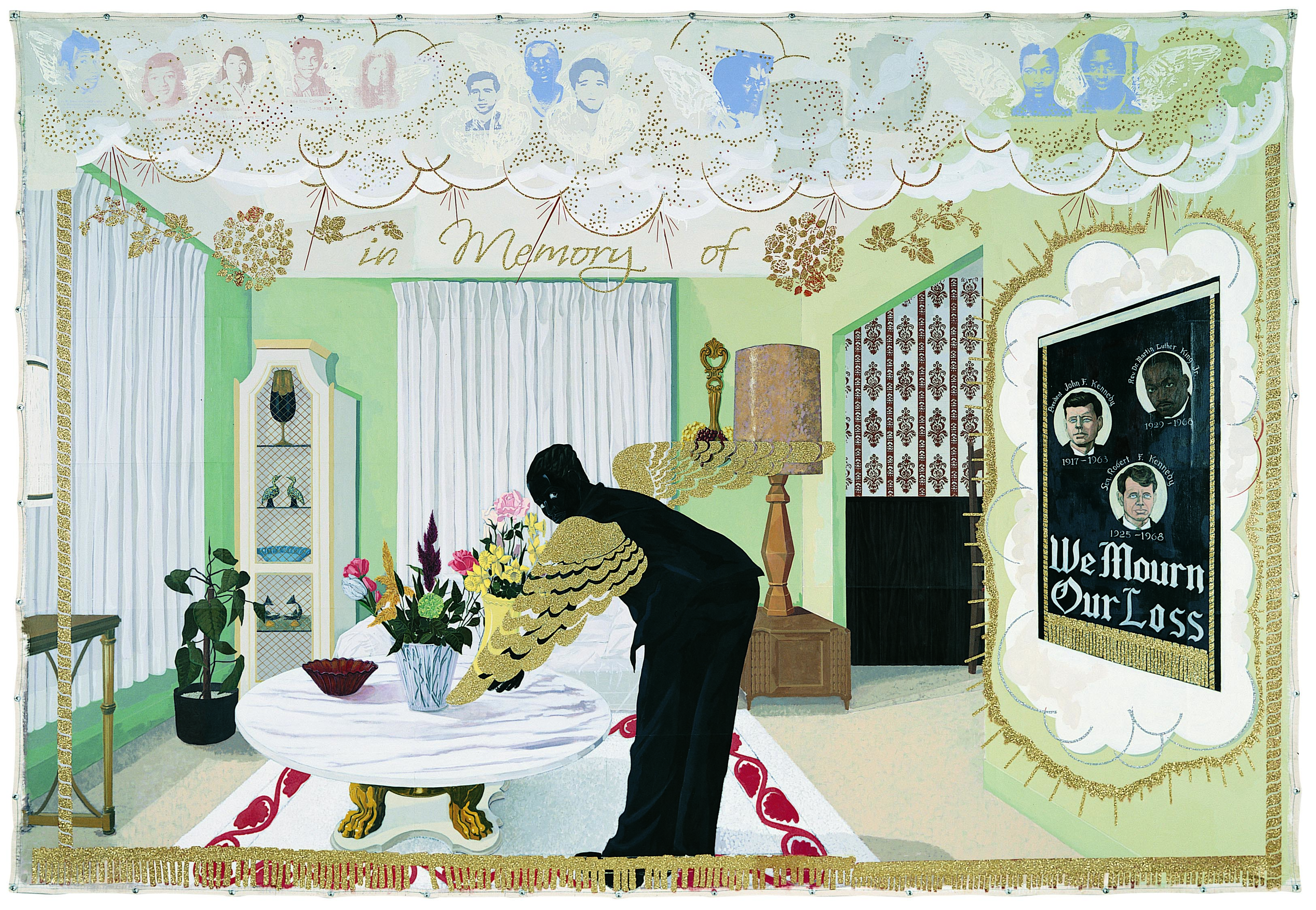

Kerry James Marshall. Souvenir I, 1997. Acrylic, collage, silkscreen, and glitter on canvas, 9 × 13 ft. (274.3 × 396.2 cm). Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Bernice and Kenneth Newberger Fund, 1997.73. © Kerry James Marshall Photo: Joe Ziolkowski, © MCA Chicago.

Throughout the exhibition, Marshall’s work celebrates the richness of everyday Black life in urban and suburban America, the beauty of Black people and, at the most basic level, their skin—rich, velvety, masterfully handled monochromes of black, whose impenetrable darkness at first glance gives way to subtle tonalities upon a closer look.

Reunited for the first time in this show, the Garden Project series (1994–95) comprises five enormous paintings of Chicago housing projects. Marshall refigures these sites of economic and social exclusion as fertile grounds for love, expression, and even magic. Countering the racist stereotypes of inner-city life that proliferated in the 1990s, these grand paintings pulsate with formal and narrative energy, even as their figures sit in contemplation or carry out everyday tasks with quiet dignity. The unstretched canvases are hung in the tradition of great narrative textiles. Nearby, in the immaculate domestic scenes made a few years later, Marshall eases into a more crystallized, pared-down approach to the figure, invoking Black history through symbolic references, like the hero portraits on the wall in Souvenir 1 (1997) or the book titles in SOB (2003). Almost heartbreaking in their simple intimacy, these paintings show the artist coming into what one might call his mature style.

In works from the late 2000s to the present, Marshall reaches the pinnacle of his craft, producing the crisp portraits of Black men and women that have become his hallmark. The aesthetic and conceptual climax of Mastry comes in one of its humbler galleries, in which a half dozen portraits (2008–10) of idealized artists and one curator meet the viewer’s gaze with confident self-possession; they are not captured in the middle of their process so much as they demonstrate their mastery of its infinite potential. In these works, Marshall clearly marks the stakes of his project: he is painting people into history, painting marginalized subjectivities into the canon. Painting is both the means and the end.

While Marshall’s evolutionary trajectory is indeed compelling, Molesworth does well by inserting counter-narratives that complicate clear ideas of progress or singularity of vision. This begins early in the exhibition, with ample room given to Marshall’s various experiments in collage, which show the young artist drawing on the visual language of (and paying homage to) predecessors like Romare Bearden and Betye Saar as late as 1992. In The Ecstasy of Communion (1990), on loan from Saar’s personal collection, Marshall paints a flayed black Christ figure onto a small piece of leather, nestled into an assemblage of paper targets and other shapes. In The Face of Nat Turner Appeared in a Water Stain (1990), the head of the legendary rebellion leader floats eerily on a dinged and water-damaged wooden plank. These small, irresolute works offer a startling counterpoint to the crisp perfection of his later paintings.

Kerry James Marshall. Rythm Mastr, 1999-present. Inkjet on Plexiglas in lightboxes. Courtesy the artist. © Kerry James Marshall.

Resistance also crops up in the small spaces dedicated to less-known aspects of Marshall’s practice, such as photography and comics. His ongoing comic strip, Rhythm Mastr, follows in the tradition of Marvel but with Black characters whose superpowers relate to fighting racism. The few panels featured in the exhibition don’t do justice to Marshall’s work in the medium, yet they give a sense of his ability to mix vicious humor with uplifting politics. They speak to his wide-ranging appetite for all forms of visual culture.

Marshall’s work in photography is also a surprise. Though it floats practically unmoored in the exhibition, Black Artist (Studio View) from 2002 is one of the more haunting works on display: an image of the artist at rest in his studio, illuminated by a black light so that only hints of objects and figures are distinguishable from the cavernous darkness. In a show that celebrates the ravishing potential of representation, the photograph’s reference to its potential inadequacies strikes a resounding, somber note.

If Mastry had filled the entire museum with Marshall’s resplendent canvases of Black life in barbershops, housing projects, and domestic spaces, few visitors would have complained. In a move both generous and challenging, it shows us everything: the perfect portraits along with the scrappy collages, the experimental photos and the mystifying abstractions, the immense history scenes and the romance paintings that could easily be printed as Hallmark cards. Such inclusion is insightful and revealing. An artist who has embraced radical, unresolved experimentation and struggled (and sometimes failed) to reconcile wide-ranging influences is much more interesting than one who never strayed far from the path to being embraced by markets and institutions, even if he knew how to get there all along.