On the evening of October 2, 2016, the people of Colombia were faced with one of the most uncertain situations in their country’s history. After four years of negotiations between the government and the largest insurgent group in the continent, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a small majority of the population—motivated by a long campaign led by the former President Álvaro Uribe—voted to reject a peace agreement that would have ended fifty years of armed conflict. Fearing an imminent return to violence and understanding the dangers of remaining still in a volatile situation, various citizen movements began mobilizing. In the week following the plebiscite, two such initiatives with seemingly similar purposes would come into conflict: Doris Salcedo’s public-art installation, Sumando Ausencias, and a citizen-organized protest camp in Bogotá’s Bolívar Square.

According to Arcadia, a rumor began circulating the halls of the National University in Bogota shortly after the votes came in, and the public reaction was that of horror; many felt it was a devastating missed opportunity. “Doris wants to do something for peace, but we still don’t know what it is,” students reportedly whispered. Soon after, a mass email was sent to the entire campus: “Doris Salcedo invites us to draw the names of victims of the decades-long conflict on seven kilometers of cloth and then put them together with needle and thread.” In response, thousands of volunteers from around the city gathered early on the morning of October 6. Among them was Mariana Sanz de Santamaria, a law student: “Once you arrived, you saw many tables filled with volunteers. There were some people cutting up the letters and others who were getting the cloth ready to be printed with the names of victims of the conflict, which had been gathered from the government’s Registry of Victims.” The pieces of cloth would later be sewn together across Bolívar Square.

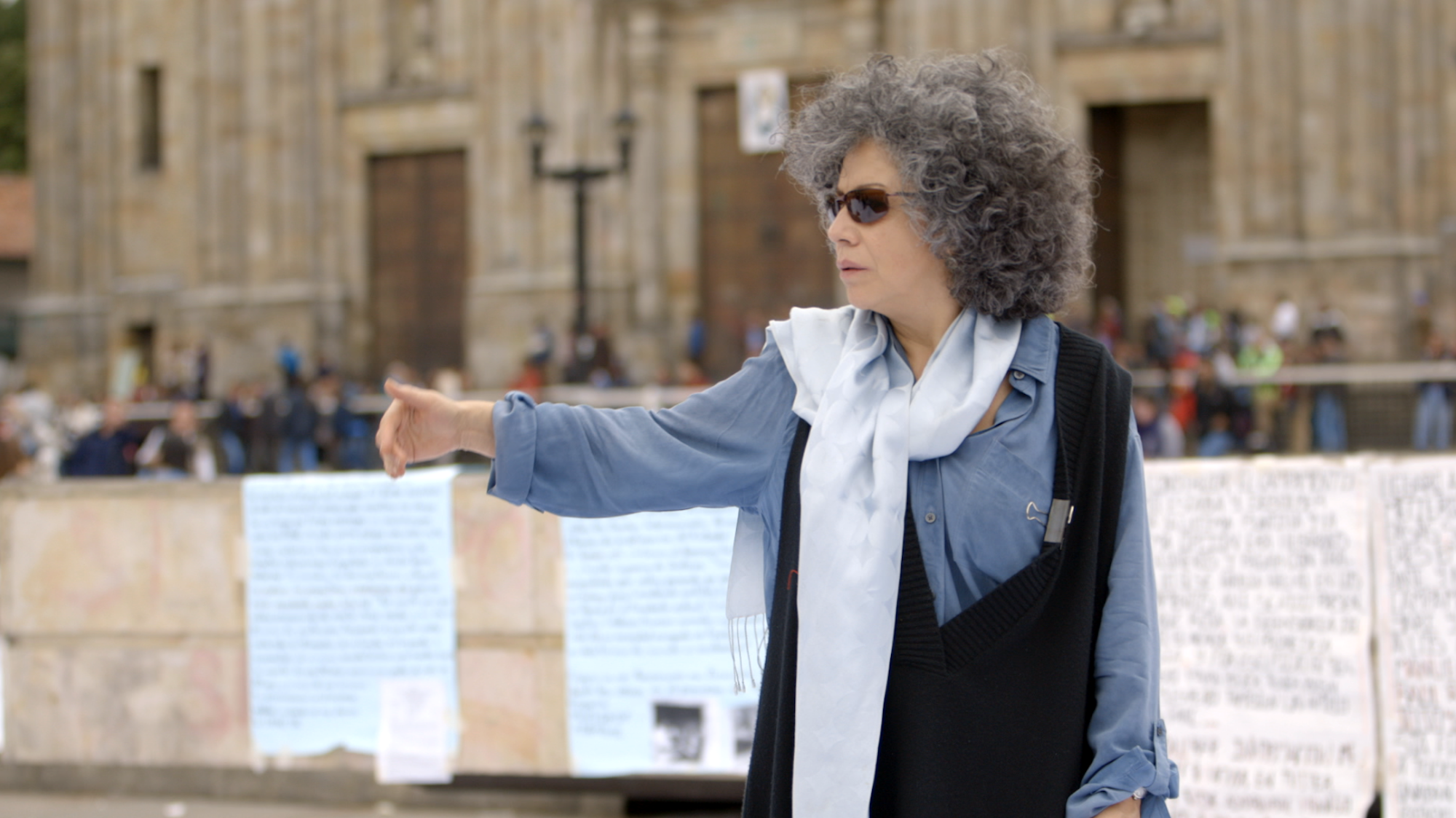

In Salcedo’s words, “Sumando Ausencias (Adding Absences) is a work of art in which the victims of the armed conflict are put in the center of Colombia’s political life by an ephemeral community formed during the making of the project: These were generous weavers who were able to gather in one single image the pain of thousands of families. The work is an act of mourning.”

Sumando Ausencias explores the possibilities of collective action over collective production. “It should be kept in mind,” the artist told national newspaper El Espectador, in one of the few interviews she agreed to participate in while organizing the project, “that the process in this case counts more than the result.” For five days, strangers sat next to each other, reflecting through the materiality of cloth on the deaths and disappearances that have taken place in regions far away from the urban context of Bogotá. “It was beautiful to see people working like ants in complete silence, each one going through their own reflection process,” says Santamaria. “I found it moving to think that the person whose name was printed on the piece of cloth I was sewing had died. For how many years have we been living in war? How many people have died and we have no idea who they are?” By creating a collective experience through sewing, Salcedo acted in the feminist tradition of exploring craft as a tool for the construction of collective memory. “Our past is something that we can build ourselves by the act of narrating it. To look back at it in the present allows for forgotten memories to resurface.”

The urban setting of Salcedo’s piece, however, also underlined the problematic nature of attempting representation in a fragmented society such as Colombia. This materialized when both Sumando Ausencias and the Campground for Peace—a citizen-led protest created under the concept of poetic action in order to demand the signing of a new peace agreement—attempted to occupy Bolívar Square. Although negotiations took place, many activists believed that the artist’s perceived elite status was interfering with their activism. Some self-identified victims who were part of the camp voted against Salcedo’s initiative, stating that they did not feel represented by the artist’s work. Carmenza Vargas, for example, a mother of a “false positive,” told Vice that most members of the camp who self-identified as victims were unable to participate in Salcedo’s project. “And now they have taken away the cloth. Who besides us will remember the names that were sewn there?”

The discourse surrounding Sumando Ausencias echos the conversations that took place in the months leading up to the national plebiscite. In a country where those living in the cities often experience violence only theoretically while those in rural areas live with it in their daily lives, the idea of collective memory can seem like an unachievable utopia. Instead of representing all of the victims of the armed conflict, Salcedo’s piece forced an already wounded society to question how and for whom memory should be built.